Category: Arts and Humanities

ORIGINAL

Studying self-concept in a sample of Peruvian secondary education students: A cross-sectional study

Estudiando el autoconcepto en una muestra de estudiantes peruanos de educación secundaria: Un estudio transversal

Jhemy Quispe-Aquise1 ![]() *,

Edwin Gustavo Estrada-Araoz1

*,

Edwin Gustavo Estrada-Araoz1 ![]() *,

Franklin Jara-Rodríguez2

*,

Franklin Jara-Rodríguez2 ![]() *,

Vicente Anastación Gavilán-Borda2

*,

Vicente Anastación Gavilán-Borda2 ![]() *,

Pamela Barrionuevo-Alosilla2

*,

Pamela Barrionuevo-Alosilla2 ![]() *

*

1Universidad Nacional Amazónica de Madre de Dios. Puerto Maldonado, Perú.

2Universidad Andina del Cusco. Puerto Maldonado, Perú.

Cite as: Quispe Aquise J, Estrada-Araoz EG, Jara-Rodríguez F, Gavilán-Borda VA, Barrionuevo-Alosilla P. Studying self-concept in a sample of Peruvian secondary education students: A cross-sectional study. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2024; 3:691. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2024691

Submitted: 21-11-2023 Revised: 14-03-2024 Accepted: 23-04-2023 Published: 24-04-2024

Editor: Dr.

William Castillo-González ![]()

ABSTRACT

Introduction: adolescence is a stage of significant physical, emotional, and cognitive changes, where young people face numerous challenges in their daily lives, especially in the educational environment. In this context, self-concept can be a determining factor in how adolescents approach these challenges and meet academic demands.

Objective: to determine the level of self-concept in a sample of Peruvian secondary education students.

Methods: quantitative, non-experimental, and cross-sectional descriptive study. The sample consisted of 125 students of both genders who were administered the AF-5 Self-Concept Scale, an instrument with adequate psychometric properties. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 25 software. A descriptive analysis of the variable and dimensions was performed, focusing on calculating their percentage distributions.

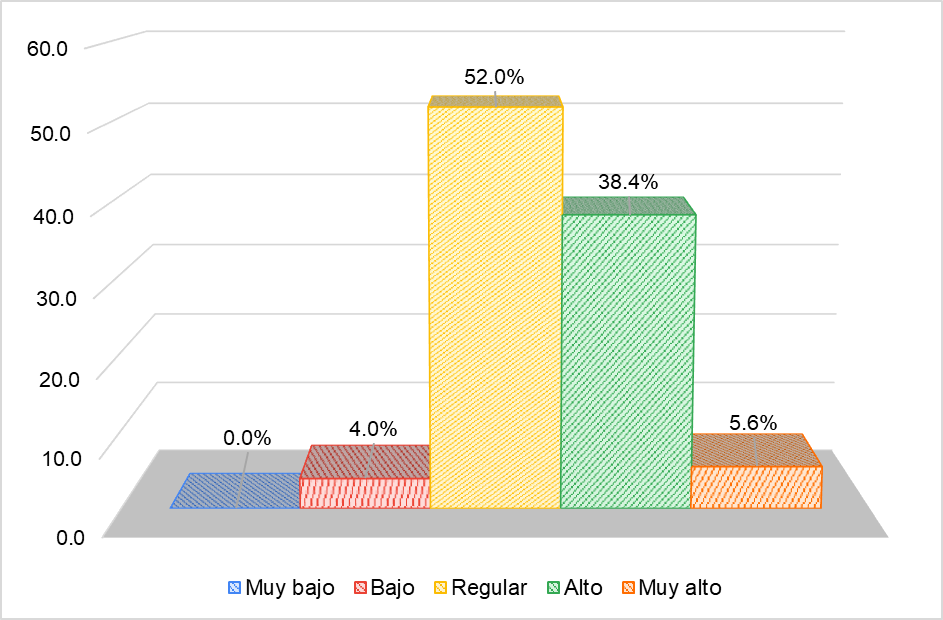

Results: the self-concept of 52 % of students was at a regular level, 38,4 % at a high level, 5,6 % at a very high level, and 4 % at a low level. This means that most students recognize some strengths in themselves, but they are also aware of their limitations and areas in which they could improve, a situation that could serve as a solid foundation for working on their personal and academic development.

Conclusions: the level of self-concept characterizing a sample of Peruvian secondary education students was regular. Therefore, it is recommended to implement strategies aimed at strengthening and improving their perception of themselves.

Keywords: Self-Concept; Students; Secondary Education; Self-Perception; Adolescence.

RESUMEN

Introducción: la adolescencia es una etapa de importantes cambios físicos, emocionales y cognitivos, donde los jóvenes enfrentan numerosos desafíos en su vida diaria, especialmente en el ámbito educativo. En este contexto, el autoconcepto puede ser un factor determinante en la forma en que los adolescentes abordan estos desafíos y enfrentan las exigencias académicas.

Objetivo: determinar el nivel de autoconcepto en una muestra de estudiantes peruanos de educación secundaria.

Métodos: estudio cuantitativo, no experimental y descriptivo de corte transversal. La muestra estuvo conformada por 125 estudiantes de ambos sexos a quienes se les aplicó la Escala de Autoconcepto AF-5, un instrumento con adecuadas propiedades psicométricas. Para llevar a cabo el análisis de datos, se utilizó el software SPSS versión 25. Se realizó un análisis descriptivo de la variable y dimensiones, centrándose en calcular sus distribuciones porcentuales.

Resultados: el autoconcepto del 52 % de estudiantes se ubicaba en un nivel regular, del 38,4 % en un nivel alto, del 5,6 % en un nivel muy alto y del 4 % en un nivel bajo. Esto quiere decir que la mayoría de estudiantes reconocen algunas fortalezas en sí mismos, pero también son conscientes de sus limitaciones y aspectos en los cuales podrían mejorar, situación que podría servirles como base sólida para trabajar en su desarrollo personal y académico.

Conclusiones: el nivel de autoconcepto que caracterizaba a una muestra de estudiantes peruanos de educación secundaria fue regular. Por lo tanto, se recomienda implementar estrategias dirigidas a fortalecer y mejorar la percepción que tienen sobre sí mismos.

Palabras clave: Autoconcepto; Estudiantes; Educación Secundaria; Autopercepción; Adolescencia.

INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is considered a crucial stage in human development and is characterized by a series of physical, emotional, and social transformations.(1) During this time of transition, adolescents are faced with the task of defining their identity and establishing a solid understanding of who they are.(2) In this context of change and exploration, self-concept (SEL) emerges as a central aspect that influences how adolescents see themselves and relate to the world around them.

Self-concept is a term that has been gaining importance in recent years in the field of psychological research (multidisciplinary, experimental, developmental, educational, or social), along with research in education and family studies, among other areas, being studied separately or in relation to multiple variables and topics.(3,4) It was conceptualized as the set of beliefs that a person has about him/herself at a given moment.(5) These beliefs are influenced by the positive or negative feelings that the person experiences towards him/herself.(6) The UA plays a fundamental role in the construction of the personality and conditions the social and emotional development of the person.(7)

In the educational setting, UA plays a crucial role in how adolescents view themselves as learners and how they approach the academic and social demands of the school environment. (8) A positive perception of themselves as learners can motivate students to set challenging goals, persist in achieving goals, and maintain a proactive attitude toward learning. (9) On the other hand, negative or underestimated UA can hinder academic performance, undermine confidence in one's abilities, and contribute to problems with self-esteem and emotional well-being. (10)

Research has been conducted on UA, identifying five dimensions: academic, social, emotional, family, and physical UA.(11) Academic UA refers to the assessment of educational performance, while social UA relates to interactions with others.(12) On the other hand, emotional UA focuses on the perception of one's emotions and responses to situations.(13) Family UA focuses on integration in the family, and physical UA encompasses the perception of appearance and physical condition.(14)

Given the crucial role that UA plays in the comprehensive development of adolescents, influencing not only their academic performance but also their psychological well-being and social relationships, understanding how they perceive and value themself is critical. Moreover, in a stage as crucial as adolescence, where identity formation and self-esteem are fundamental, studying UA can provide a more complete picture of their needs and challenges. Therefore, the present research can provide valuable information for designing support and guidance strategies that promote positive UA and strengthen students' identity, thus contributing to their academic success and personal development. Finally, the objective of the present research was to determine the level of UA in a sample of Peruvian high school students.

METHODS

The study adopted a quantitative approach in order to collect data and identify patterns of behavior within the sample analyzed. The design was non-experimental since it did not involve manipulation of the variable AU but was limited to observing it in its natural context. In addition, it was descriptive and cross-sectional since the characteristics of the study variable were explored at a single point in time.(15)

The population consisted of 185 students of both sexes who were in the last cycle of secondary education in an educational institution located in the district of Las Piedras (Peru). The sample consisted of 125 students. It should be clarified that this sample size was determined using a simple random probability sampling method, which ensured a confidence level of 95 % and a significance of 5 %, which guarantees the representativeness of the sample and the validity of the results obtained in the study.

UA was considered as the study variable, which was categorized into 5 levels, considering the following cut-off points: very low (30 - 53), low (54 - 77), regular (78 - 101), high (102 - 125) and very high (126 - 150).

The data collection technique was the survey, while the instrument was the AF-5 Self-Concept Scale.(12) This scale evaluates the global perception that a person has of him/herself in different areas of his/her life. It is made up of 30 items with 5 response alternatives ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always) and presents five dimensions: AU academic (6 items), social (6 items), emotional (6 items), family (6 items) and physical (6 items). Previous research conducted in the Peruvian context(16) determined that the instrument had adequate metric properties (Aiken's V= 0,800; α= 0,844).

Data collection was performed after obtaining the pertinent authorizations from the corresponding educational authorities. To ensure student participation, the survey was carried out in person at the educational institution. A cordial invitation to participate was extended to the students, accompanied by detailed instructions for completing the data collection instrument. During this process, which lasted approximately 20 minutes, special attention was paid, and follow-up was provided to ensure the quality of the responses obtained.

To carry out the data analysis, SPSS version 25 software was used. A descriptive analysis of the variables and dimensions was performed, focusing on calculating their percentage distributions.

The research was carried out in strict accordance with ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from the student's parents, who were previously informed about the purpose and procedures of the study, as well as about the rights of participation and the guarantee of confidentiality of their children's information. Finally, the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were respected, with the aim of safeguarding the well-being and integrity of all the students.

RESULTS

Figure 1 shows that the UA of 52 % of students was at a regular level, 38,4 % at a high level, 5,6 % at a very high level, and 4 % at a low level. It should be noted that no student presented a very low UA. This means that most students have a moderate opinion of their abilities, achievements, and personal characteristics.

Figure 1. Distribution of percentages of the self-concept variable

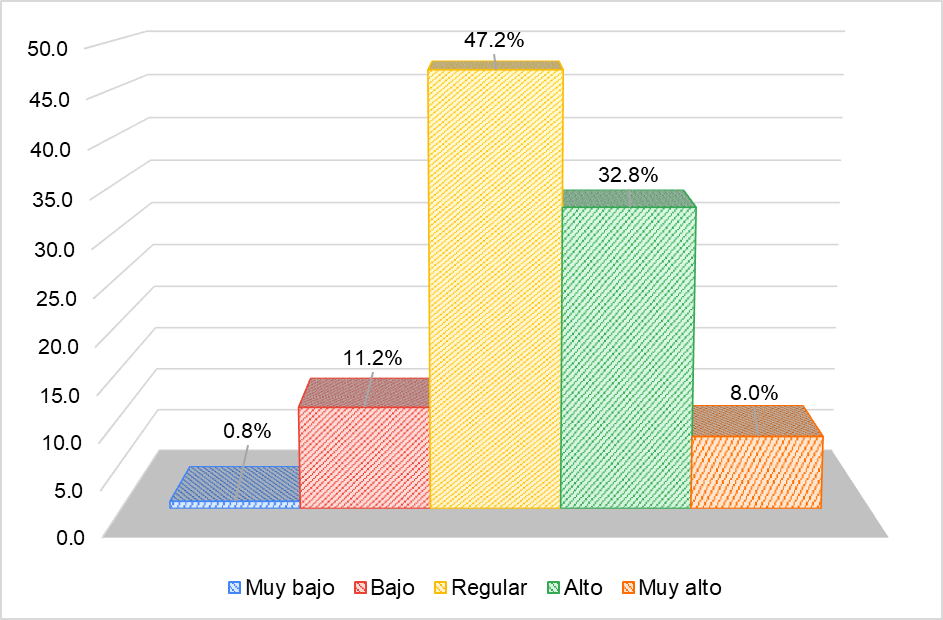

Figure 2 shows that the academic UA level of 47,2 % of the students was fair, 32,8 % was high, 11.2% was low, 8% was very high, and 0.8% was deficient. This result indicates that students have a moderate perception of their abilities and academic performance, i.e., they feel confident in some courses but may experience doubts or insecurities in others.

Figure 2. Distribution of percentages of the academic self-concept dimension

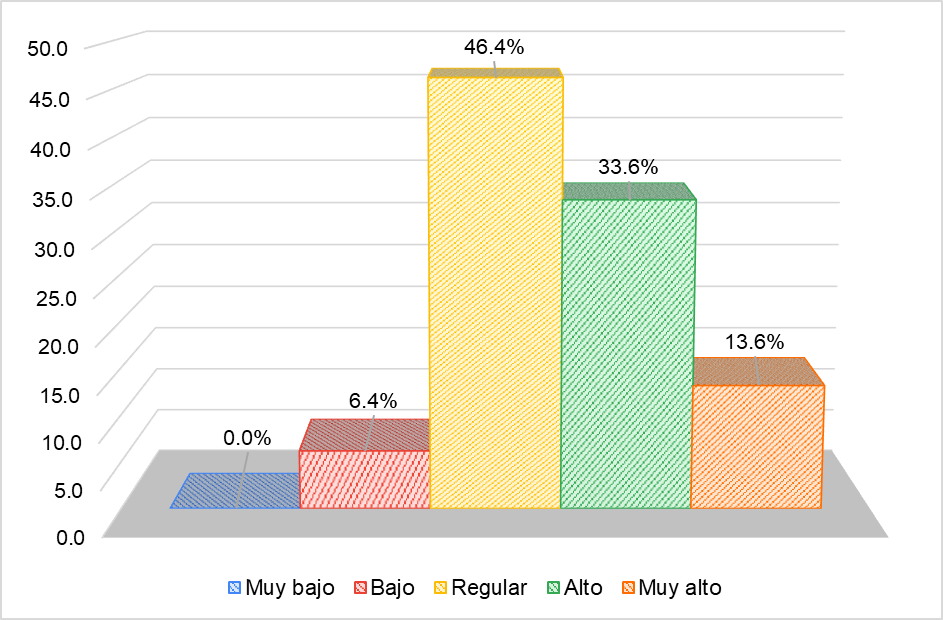

According to Figure 3, the level of social UA of 46,4 % of the students was regular, 33,6 % was high, 13,6 % was very high, and 6,4 % was low. It should be noted that none of the students had very low social UA. The above indicates that the students have a balanced perception of their abilities, behaviors, and social relations.

Figure 3. Distribution of percentages of the social self-concept dimension

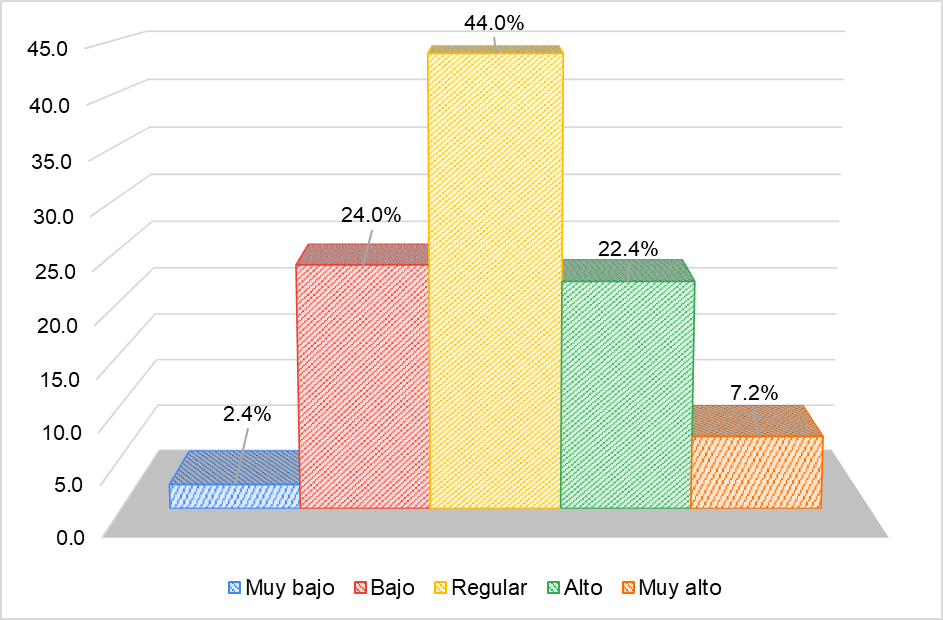

According to Figure 4, the level of emotional UA of 44 % of the students was regular, 24 % was low, 22,4 % was high, 7,2 % was very high, and 2,4 % was deficient. This means that students are characterized by having a balanced perception of their emotions, feelings and abilities to manage them. Likewise, they can sometimes experience a varied range of emotions, both positive and negative, and have the ability to recognize and manage them appropriately.

Figure 4. Distribution of percentages of the emotional self-concept dimension

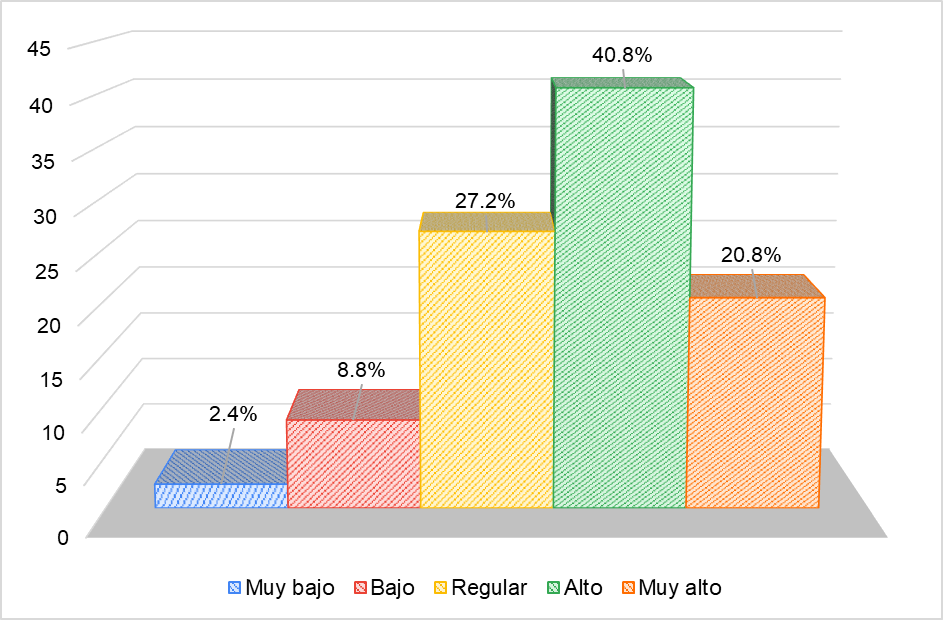

Figure 5 shows that the level of family UA of 40,8 % of the students was high, 27,2 % was fair, 20,8 % was very high, 8,8 % was low, and 2,4 % was deficient. The above data indicate that students are characterized by feeling valued, supported, and secure in the family environment and experience a strong emotional connection with their family members.

Figure 5. Distribution of percentages of the family self-concept dimension

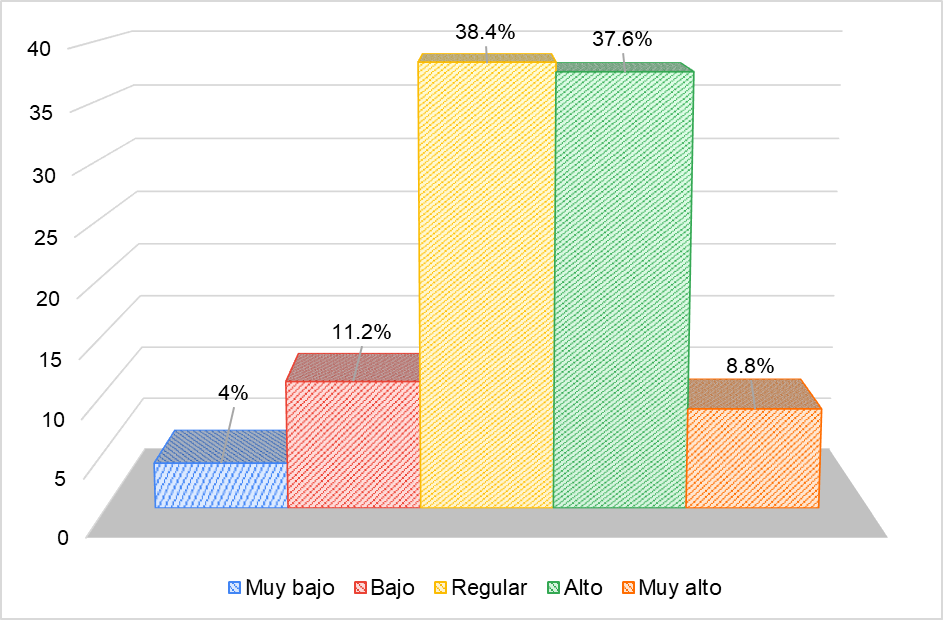

Figure 6 shows that the level of physical AU of 38,4 % of the students was fair, 37,6 % was high, 11,2 % was low, 8,8 % was very high, and 4 % was deficient. These data suggest that, occasionally, students have a balanced and realistic perception of their physical appearance and body. In addition, it implies that on certain occasions, they accept themselves with their virtues and imperfections and do not experience excessive concern about their appearance.

Figure 6. Percentage distribution of the physical self-concept dimension

DISCUSSION

The main result of the present research reveals that 52 % of the evaluated students manifested a level of UA classified as regular, while 38,4 % exhibited a high level, 5,6 % reached a very high level, and the remaining 4 % were at a low level. This distribution in UA levels suggests that most students have a reasonably positive perception of themselves, which could be beneficial to their personal and academic development by providing them with a solid foundation to face challenges and take advantage of growth opportunities.

There is a variety of research to support the above findings. For example, in a study conducted in Peru(16), it was found that 64,5 % of the students evaluated presented a partially adequate perception of themselves, including their attitudes, emotions, and level of knowledge of their abilities, as well as their social acceptance. Likewise, another research conducted in Peru(17) found that 50,3 % of the participants showed a moderate level of general self-esteem, which covered various aspects of their lives, such as family environment, academic context, social relationships, emotional state, and perception of their physical appearance.

Another finding shows that academic, social, emotional, and physical UA were rated at a fair level, while family UA was rated at a high level. This suggests that students have a balanced perception of their abilities, achievements, social relationships, emotions, and physical appearance without particularly standing out in any of these areas. On the other hand, family UA was rated at a high level, indicating that the participants have a positive and satisfactory perception of their role and integration in the family environment. This higher valuation of family UA may reflect the importance of family relationships in the formation of adolescents' identity and self-esteem, as well as the positive influence that these relationships can have on their emotional and social well-being.

Similar results were obtained in research conducted in Peru,(18) in which they identified that the dimensions with the highest scores are personal and family UA, while academic, social, emotional, and physical UA presented average scores. Similarly, it is related to the findings of a study also conducted in Peru (19) in which they found that the academic, social, emotional, family and physical UA dimensions were rated at an average level. These two investigations support the idea that, in the Peruvian educational context, students tend to perceive themselves in a balanced way in terms of their academic skills, social relationships, emotional state, and physical appearance, standing out, especially in the valuation of their personal and family UA.

During adolescence, students are immersed not only in the acquisition of academic knowledge but also in the construction of their identity and self-image.(20,21) It is imperative to recognize that fostering a healthy UA not only impacts the student's self-esteem and confidence,(22) but also his or her ability to face challenges with determination.(23) An educational and social environment that fosters acceptance, understanding, and personal growth is therefore required, thus providing young people with the tools necessary to function safely and resiliently in a constantly changing world.(24,25)

The present research is not without some limitations that could influence the interpretation of the results. First, the sample was small and homogeneous, which could compromise the representativeness of the findings. In addition, the use of a self-administered instrument could introduce social desirability biases. For future research, it is recommended that multicenter studies covering educational institutions of various types (public and private) and settings (urban and rural) be carried out in order to obtain a more diverse and representative sample. Likewise, it would be beneficial to complement quantitative data collection with qualitative methods to obtain a more complete and in-depth understanding of the topic in question.

CONCLUSIONS

The results allow us to conclude that the level of UA that characterized a sample of Peruvian high school students was regular. This means that most students recognized some strengths in themselves but were also aware of their limitations and aspects in which they could improve, a situation that would serve as a solid basis for working on their personal and academic development. Therefore, it is suggested to implement psychosocial interventions in the educational setting that promote the development of self-esteem and self-confidence. These strategies include mentoring programs, social and emotional skills workshops, as well as extracurricular activities that promote recognition of individual achievements. It is also suggested that psychological support programs be implemented for those students who present a more vulnerable AU in order to help them overcome obstacles and strengthen their emotional well-being and academic success.

REFERENCES

1. McLaughlin K, Garrad M, Somerville L. What develops during emotional development? A component process approach to identifying sources of psychopathology risk in adolescence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17(4):403-410. https://doi.org/10.31887%2FDCNS.2015.17.4%2Fkmclaughlin

2. Branje S, De Moor E, Spitzer J, Becht A. Dynamics of identity development in adolescence: A decade in review. J Res Adolesc. 2021;31(4):908-927. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fjora.12678

3. Hapsari H, Huang M, Kanita M. Evaluating self-concept measurements in adolescents: A systematic review. Children (Basel). 2023;10(2):399. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fchildren10020399

4. Elder J, Cheung B, Davis T, Hughes B. Mapping the self: A network approach for understanding psychological and neural representations of self-concept structure. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2023;124(2):237-263. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000315

5. Denche A, Mayordomo N, Galán C, Mañanas C, Adsuar J, Rojo J. Differences in self-concept and its dimensions in students of the third cycle of primary school, obligatory secondary education, and baccalaureate. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(7):987. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fhealthcare11070987

6. Londoño D, Lubert C, Sepúlveda V, Ferreras A. Estandarización de la Escala de autoconcepto AF5 en estudiantes universitarios colombianos. Ansiedad y Estrés. 2019;25(2):118-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anyes.2019.06.001

7. Carranza R, Bermúdez M. Análisis psicométrico de la Escala de Autoconcepto AF5 de García y Musitu en estudiantes universitarios de Tarapoto (Perú). Interdisciplinaria. 2017;34(2):459-472.

8. Zhang D, Cui Y, Zhou Y, Cai M, Liu H. The role of school adaptation and self-concept in influencing Chinese high school students' growth in math achievement. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2356. https://doi.org/10.3389%2Ffpsyg.2018.02356

9. Liu Y, Di S, Zhang Y, Ma C. Self-concept clarity and learning engagement: The sequence-mediating role of the sense of life meaning and future orientation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(6):4808. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fijerph20064808

10. Casino A, Llopis M, Llinares L. Emotional Intelligence profiles and self-esteem/self-concept: An analysis of relationships in gifted students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1006. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fijerph18031006

11. López D, Bernal M. Percepciones del autoconcepto en estudiantes de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria a través de la mediación artística. REIFOP. 2023;26(3):195–209. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.560861

12. García F, Musitu G. AF5: Autoconcepto Forma 5. Madrid: TEA Ediciones; 1999.

13. Mato O, Ambris J, Llergo M, Mato Y. Autoconcepto en adolescentes considerando el género y el rendimiento académico en Educación Física. Univ. Soc. 2020;12(6):22-30.

14. García F, Musitu G. AF-5 Autoconcepto Forma 5. Madrid, España: TEA; 2014.

15. Hernández R, Mendoza C. Metodología de la investigación: las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta. México: McGraw-Hill; 2018.

16. Estrada E, Mamani H. Clima social familiar y autoconcepto en estudiantes de una institución educativa estatal. Rev. Cient. Cienc. Salud. 2020;13(1):37-43. https://doi.org/10.17162/rccs.v13i1.1344

17. Malca A, Rivera L. Clima social familiar ¿Qué relación tiene con el autoconcepto en adolescentes del Callao? CASUS. 2019;4(2):120-129. https://doi.org/10.35626/casus.2.2019.208

18. Tacca D, Cuarez R, Quispe R. Habilidades sociales, autoconcepto y autoestima en adolescentes peruanos de educación secundaria. RISE. 2020;9(3):293–324. https://doi.org/10.17583/rise.2020.5186

19. Llanca B, Arnas N. Clima social familiar y autoconcepto en adolescentes de una institución educativa de Lima Norte. CASUS. 2020;5(1):26-33. https://doi.org/10.35626/casus.1.2020.245

20. Pfeifer J, Berkman E. The development of self and identity in adolescence: Neural evidence and implications for a value-based choice perspective on motivated behavior. Child Dev Perspect. 2018;12(3):158-164. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fcdep.12279

21. Kulakow S. Academic self-concept and achievement motivation among adolescent students in different learning environments: Does competence-support matter? Learn Motiv. 2020;70:101632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2020.101632

22. Baudson T, Weber K, Freund P. More than only skin deep: Appearance self-concept predicts most of secondary school students' self-esteem. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1568. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01568

23. Karlen Y, Hirt C, Liska A, Stebner F. Mindsets and self-concepts about self-regulated learning: Their relationships with emotions, strategy knowledge, and academic achievement. Front Psychol. 2021;12:661142. https://doi.org/10.3389%2Ffpsyg.2021.661142

24. Bakadorova O, Raufelder D. The Interplay of students' school engagement, school self-concept and motivational relations during adolescence. Front Psychol. 2017;8:2171. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02171

25. Saß S, Kampa N. Self-concept profiles in lower secondary level - An explanation for gender differences in science course selection? Front Psychol. 2019;10:836. https://doi.org/10.3389%2Ffpsyg.2019.00836

FINANCING

The authors received no funding for the development of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Jhemy Quispe-Aquise, Edwin Gustavo Estrada-Araoz.

Data curation: Jhemy Quispe-Aquise, Edwin Gustavo Estrada-Araoz.

Formal analysis: Jhemy Quispe-Aquise, Edwin Gustavo Estrada-Araoz.

Acquisition of funds: Franklin Jara-Rodríguez, Vicente Anastación Gavilán-Borda.

Research: Jhemy Quispe-Aquise, Franklin Jara-Rodríguez.

Methodology: Jhemy Quispe-Aquise, Franklin Jara-Rodríguez.

Project administration: Edwin Gustavo Estrada-Araoz.

Resources: Franklin Jara-Rodríguez, Vicente Anastación Gavilán-Borda.

Software: Vicente Anastación Gavilán-Borda, Pamela Barrionuevo-Alosilla.

Supervision: Edwin Gustavo Estrada-Araoz, Pamela Barrionuevo-Alosilla.

Validation: Jhemy Quispe-Aquise, Vicente Anastación Gavilán-Borda.

Visualization: Jhemy Quispe-Aquise, Pamela Barrionuevo-Alosilla.

Editing - original draft: Edwin Gustavo Estrada-Araoz.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Edwin Gustavo Estrada-Araoz.