Category: Education, Teaching, Learning and Assessment

ORIGINAL

Regional Educational Policies and Critical Interculturality in Rural Areas of the Province of Abancay - Apurímac, 2023

Políticas Educativas Regionales e Interculturalidad Crítica en Áreas Rurales de la Provincia de Abancay - Apurímac, 2023

Ernestina Choccata-Cruz1 ![]() *, Rosa Villanueva-Figueroa1

*, Rosa Villanueva-Figueroa1

![]() *, Veronica

Galvez-Aurazo1

*, Veronica

Galvez-Aurazo1 ![]() *, Gustavo Zarate-Ruiz1

*, Gustavo Zarate-Ruiz1 ![]() *, Elder Miranda-Aburto2

*, Elder Miranda-Aburto2 ![]() *

*

1Universidad César Vallejo. Perú.

2Universidad Nacional Federico Villareal. Perú.

Cite as: Choccata-Cruz E, Villanueva-Figueroa R, Galvez-Aurazo V, Zarate-Ruiz G, Miranda-Aburto E. Regional Educational Policies and Critical Interculturality in Rural Areas of the Province of Abancay - Apurímac, 2023. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias 2024; 3:637. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2024637.

Submitted: 15-12-2023 Revised: 08-02-2024 Accepted: 21-03-2024 Published: 22-03-2024

Editor: Dr.

William Castillo-González ![]()

ABSTRACT

The research work was carried out with the aim of analyzing regional educational policies and critical interculturality in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023. The research is basic, qualitative and design-based, phenomenological-hermeneutic. The study population consisted of specialists, principals, teachers and students of the secondary education level of rural areas of the UGEL (Local Educational Management Unit) Abancay and the sample consisted of: 4 specialists from the DREA (Regional Directorate of Education of Apurímac), 3 specialists from the UGEL Abancay, secondary level, 6 rural education teachers from the EBR (Regular Basic Education), secondary school level, 6 directors and 6 students from rural schools in the province of Abancay. The following data collection instruments were used: semi-structured interview guide, documentary review form and non-participant observation guide. From the research it is concluded that the PERs (Regional Educational Policies) of Apurimac do not implement strategies of CI (critical interculturality) and the educational communities of rural schools do not know about the current PER (Regional Educational Project), but the native students demand the vindication of their language in educational and social processes.

Keywords: Educational Policy; Education; Intercultural Education; Critical Interculturality.

RESUMEN

El trabajo de investigación se realizó con la finalidad de analizar las políticas educativas regionales y la interculturalidad crítica en la educación secundaria de las zonas rurales de la provincia de Abancay, departamento de Apurímac, 2023. La investigación es básica, cualitativa y de diseño, fenomenológico-hermenéutica. La población de estudio estuvo conformada por especialistas, directores, docentes y estudiantes del nivel de educación secundaria de las zonas rurales de la UGEL (Unidad de Gestión Educativa Local) Abancay y la muestra estuvo conformada por: 4 especialistas de la DREA (Dirección Regional de Educación de Apurímac), 3 especialistas de la UGEL Abancay, nivel secundaria, 6 docentes de educación rural de la EBR (Educación Básica Regular), nivel secundaria, 6 directores y 6 alumnos de escuelas rurales de la provincia de Abancay. Se utilizaron los siguientes instrumentos de recolección de datos: guía de entrevista semiestructurada, ficha de revisión documental y guía de observación no participante. De la investigación se concluye que los PER (Políticas Educativas Regionales) de Apurímac no implementan estrategias de IC (interculturalidad crítica) y las comunidades educativas de las escuelas rurales desconocen el PER (Proyecto Educativo Regional) vigente, pero los estudiantes nativos exigen la reivindicación de su lengua en los procesos educativos y sociales.

Palabras clave: Política Educativa; Educación; Educación Intercultural; Interculturalidad Crítica.

INTRODUCTION

The research problem considered education in the context of the scientific and technological advances of society and the increase in asymmetries due to the COVID 19 pandemic. The sustainable progress of countries requires educational improvements in order to obtain employment, overcome prejudices and promote equal opportunities. In this way, quality education must be ensured, contemplated in the targets of Sustainable Development Goal 4, "Quality Education", in which the cultural diversity of peoples was valued (United Nations, 2020).

For Pita (2020), the indigenous peoples of Latin America demand a quality education that includes the incorporation of their languages and ancestral wisdom for a better society. Quechua is an indigenous and cross-border language used in Peru and other Latin American countries (UNICEF, 2023). In Latin America, native languages have been relegated, discriminated against, and many of them have become extinct, as is the case of Puquina. In Peru, Quechua presents dialectal diversity in South American countries, which makes it a recognized linguistic family in the National Document of Native Languages of Peru (BDPI, 2013). The subsistence of Quechua in Peru until 2023 is explained by the fact that it was the language that the Spaniards used to indoctrinate the native population in the Catholic religion. Peru is a multilingual country due to the diversity of languages, and Quechua or "Kichwa" is the main native language in agricultural, commercial and social activities, but not in formal education in the rural areas of the highlands, especially in the department of Apurímac.

The last census of 2017 carried out by INEI (National Institute of Statistics and Informatics) showed that the population of the department of Apurímac leads in the use of the Quechua language (Andrade, 2019; El Peruano, 2021). Therefore, the linguistic and academic situation of the use of Quechua influences the low academic performance of students in Regular Basic Education (EBR), mainly in rural areas. In 2021, Apurimac ranked 15th in the Regional Competitiveness Index (INCORE) and in the education indicator, illiteracy among people aged 15 and over was ranked 24th (IPE, 2021). This reality demands a hermeneutical phenomenological study.

In Peru and other Latin American countries, the demands of indigenous peoples are seconded, as they are, in institutions and in public discourse, which gives the impression that the "problem" has been solved, as well as the ongoing struggles of indigenous movements to build societies, states, and a humanity that empathizes with their peers (Walsh, 2009). Likewise, it is necessary to recognize that schools, colleges and higher education centers are scenarios of social analysis-struggle within the framework of the policy to generate PERs with a decolonial character and critical interculturality (CI), built from their population (Viaña et al., 2010). Walsh & Monarch, 2020). Then, education in multilingual contexts in Peru will cease to be monolingual and discriminatory against indigenous people.

In Peru, the National Educational Project-PEN 2036 recognized the problem of cultural diversity, discriminatory attitudes and political decisions that have not favored indigenous cultures. Indigenous people find it difficult to have an education that guarantees their training and professional development (CNE, 2020;

López (2019) reported that educational policies were implemented, but even so, in 2019 the highest rate of students who dropped out of schools and colleges in rural areas was reached in Latin America. In the department of Apurímac, students from rural schools are born into homes where Kichwa is language 1 (L1) and is used in all activities, but when they enter early education all interaction on the part of the teacher is in Spanish. This imposition generates feelings of shyness, fear of using the L1, fear of making mistakes in Spanish. Therefore, the general problem of the research was, what is the reality of PERs and CI (critical interculturality) in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023?

Considering the justifications or reasons that describe a phenomenon to analyze and explain (Fernández-Bedoya, 2020), in this case about PERs and CI. The theoretical justification consisted of academic reflection on situations where the State does not include indigenous languages in formal education to date (Zuchel & Leiva, 2020).

The construction of the PERs that evidenced gaps in the intercultural approach with a critical, reflexive and constructive character in a Quechua-speaking region where monoculturalism reflected the sociocultural reality of today's society and its axiological problems (Correa & Guzmán, 2019). Because the academic discussion made it possible to reflect on the two categories of research in rural schools in a Quechua-speaking region.

The methodological justification generated the creation of new instruments for data collection (Fernández-Bedoya, 2020) in the hermeneutic phenomenological method that allowed the experience to be collected through the semi-structured interview guide applied to education professionals who determine the praxis of PERs and CIs in rural areas of the province of Abancay. Subsequently, the analysis and conclusions of the conceptions that the members of the research unit formulated, extracting their essence, regarding the PERs and CI in rural areas of the province of Abancay, were carried out, which, in an evocative way, showed the essential findings of the investigated phenomenon.

The practical justification of the study was the need to implement CI and PERs in schools in rural areas of the province of Abancay. CI guarantees the presence of rural dwellers with their culture and ancestral knowledge in the multicultural system (Zuchel & Leiva, 2020). Thus, vindicating the inhabitants of rural areas through the execution of PERs and CIs, which involves unveiling the knowledge of the original cultures that were oppressed since the time of colonization and that persists to date (Morales & Vélez, 2022). Therefore, the analysis of the PERs and CIs in rural areas of the province of Abancay is in demand.

Therefore, the general objective of the research was to analyze the PERs and CI in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023; The specific objectives were: (a) To identify regional educational policies in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023 and (b) To describe critical interculturality practices in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023.

Theoretical framework

In the state of the art, previous studies that have addressed the topic of study (Torres-Rodríguez & Monroy-Muñoz, 2020) in the national and international context were considered.

At the national level, Humpiri et al. (2021) in their research had as their main objective, to analyze the educational policies implemented by the Ministry of Education (MINEDU) to analyze the problem of reading comprehension in the country between 2001 and 2018. They used a cross-sectional mixed research approach, and the sample consisted of 86 teachers teaching in the second grade of primary school in the province of San Román. The most outstanding results revealed that the teachers surveyed perceived the training provided by MINEDU as unreliable and that they were unaware of the levels and abilities in reading comprehension established in the national curriculum for regular basic education (CNEB). As a result, the Peruvian State has not implemented clear and effective policies to improve reading comprehension during the period studied. In addition, established programs have been deactivated over time and have had a limited impact on solving this problem, as evidenced by the results of the latest PISA exam. Finally, it was found that teachers are more familiar with the Reading Plan and the Book Bank compared to other programs and regulations.

In times of COVID 19, Mera (2020) in her research the objective was to identify the changes that occurred in the educational field in Peru during Covid-19. It employed a basic research methodology with a qualitative approach and a phenomenological design was applied. To obtain data, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 5 participants. The results revealed that rural sectors were more disadvantaged compared to urban areas, making it difficult for students to access and participate normally in virtual classes. Thus, equal access to education was affected, especially in rural populations. It was recommended that the government invest more in education, providing equipment to low-income families and granting vouchers to the neediest students to prevent them from missing classes.

In the context of Lima, Flores-Pérez (2019), in his research had the objective of analyzing the impact of public policies (PP) on the reduction of social inequalities, with a qualitative approach methodology, the important result was the existence of 03 gaps in the social that are education, health and work; In conclusion, the local PPs in Chorrillos only attend to safety and there is a demand for food and mobility. Local PPs are based on a national matrix and municipalities must plan PPs that respond to the demands and expectations of the community.

Likewise, Sulca (2019) in his research aimed to generate a grounded theory of the intercultural dialectical approach in regular basic education (EBR), through the method of constant comparison and assuming the conclusion that the intercultural dialectical approach is the interrelation between different cultures in a good life. As a result, the intercultural dialectical approach promotes the coexistence, dialogue and interrelation of cultures in intercultural contexts that lead to the development and progress of each culture in a socio-political praxis of harmony with its peers and with nature. The intercultural dialectical approach is a proposal to implement the PERs with CI principles in the multicultural and multilingual scenario of Peru.

Also, Cépeda et al. (2019), in her research, the objective was to describe the conceptions of interculturality in educational practice in the classroom and in curriculum planning. Through semi-structured interviews, observations, and analysis of learning units; As a result, teachers' conceptions of interculturality include: the affirmation of one's own culture, the encounter with other languages and cultures, and the exchange between cultures.

Considering Tubino's (2019) research, he highlighted that some Latin American countries are implementing identity politics to date. The most relevant conclusion is that interculturalism must be practiced in order to foster harmonious coexistence. Therefore, Latin American society must promote the implementation of critical interculturality that allows interculturalism to be re-examined as identity politics, for its reformulation individuals must be considered as full participants in social interaction.

CI is a model that allows us to show how established rules negatively affect the development of the capacities of people who are unjustly underestimated. And it is urgent to denaturalize injustice in society and show that it is a historical product that can be deconstructed and replaced as a dignifying practice for a harmonious coexistence Tubino (2019).

At the international level, in the context of Mexico, Martínez (2023) in his research referred to the objective of examining whether there are specific policies for multigrade schools implemented by the Mexican state. Through documentary research, the educational policies established from 1995 to the present were reviewed, in order to analyze whether PP have been developed for these schools or if they have been subsumed by the educational policies intended for graduate schools. Graduate schools have predominated as the hegemonic form of organization, which has led political-educational efforts to focus on this modality, relegating the implementation of PPs that seek to improve the quality of education in multigrade schools. The latter emerged as a strategy to expand educational coverage, which should involve the creation of specific policies or the continuation of strategies led by previous administrations. However, it seems that these specific needs have been neglected, which raises the relevance of evaluating and redesigning more appropriate educational policies for multigrade schools.

For Manzanilla-Granados et al. (2023) in its research on EP (educational policies), the objective was to carry out an analysis of the EPs proposed in three national training plans in Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay. The methodology used was comparative, which made it possible to identify similarities and differences between the plans and find trends present in each one. Based on the results obtained, it was concluded that understanding the interrelationship between the categories requires an in-depth analysis that allows us to visualize how these categories are connected and related to each other in a process that seeks to improve learning.

In Colombia, García and León (2021), in their research, the objective was to describe the articulation of interculturality and decolonization in the learning process of a school. The research was descriptive in nature and a mixed approach was employed; A questionnaire was used to collect data. The results revealed that the articulation of interculturality and decolonization is inadequate, and implies in the praxis the principles of equality, respect for cultural diversity and human rights for a liberatory approach. Because the principles referred to are not adequately reflected in the curricular contents. Thus, interculturality is a pedagogical tool that generates the development and creation of dialogue between cultural participants within a framework of legitimacy and equality. Added to this is decolonization that challenges the traditional ways in which learning has been conceived or carried out in school classrooms to generate processes of formation of nations in Latin America with the belonging of their own (knowledge and cultural practices) that are not part of the current practice in education.

For Compañ-García (2020), in her research, the objective was to describe and analyze the educational policy measures designed and implemented by the Mexican government in response to the health contingency. Faced with this emergency, the education authorities opted for distance education using technological resources to ensure continuity in school for students. However, it was observed that these educational policy actions in Mexico were not equitable or inclusive, since a sector of the population was not served and continues to be excluded from these benefits.

Additionally, Mosquera (2020) referred in his research on memory policies in schools in Latin America in the face of armed conflicts; and the important result is that the Colombian education system does not consider policies of memory of the armed conflict of the FARC-EP. The relevant conclusion is that, to date, the memory of the armed conflict of the FARC-EP is not considered in the EPs of Colombia. EPs should consider policies for the memory of conflicts that occurred and the formation of citizens with national identity.

In Venezuela, Díaz-Guillén and Vargas-Monzón (2020) in their research, the objective was to investigate the conception of democracy in the 21st century and its relationship with the fulfillment of the PP according to other previous studies. To this end, a qualitative approach was followed under the postpositivist paradigm, using the technique of documentary research and content analysis arrived at the important result, reflections from the hermeneutic perspective and the conclusion was, public EPs must guarantee democracy as a social right and must be sustainable. Likewise, Pacheco-Bohórquez et al. (2020) conducted a comparative study of early childhood education in Colombia, Norway and Chile. They examined various categories in order to understand the complexity of the training processes at this stage, taking into account the particular context of the countries analyzed. They used a methodology based on documentary review and the main conclusion, it is necessary to make greater efforts in terms of investment and articulation of the structure itself.

In Latin American contexts, Freire and Leyva (2020) in their research on intercultural bilingual education in Ecuador indicated the objective of analyzing intercultural education. The methodology used consisted of searching for scientific evidence published between 2015 and 2019, conducting a systematic review with a quantitative approach. To this end, hermeneutic, content analysis, analytical-synthetic, and statistical methods were used. Among the main findings, the topic of intercultural education stood out and the conclusion, intercultural education manages to incorporate a series of positive elements that influence good educational practice, but it is necessary to continue researching and deepening to fully understand its impact on the educational context of the country.

Also, Pérez (2020) in his research, phenomenology and decolonization, indicates that this design generated a significant impact on the understanding of Latin American culture and identity. The openness to various fields of contemporary knowledge made it possible to question the biases of positivist scientism and to turn our gaze towards ourselves, examining both conservative and liberal traditions in order to forge new paths in the philosophical field and self-knowledge.

Pérez's (2020) significant finding was that the research's contributions fostered universality, a key element for decolonization, emancipation, and identity affirmation in Latin America. In this context of reception, a strand of phenomenological-existential thought emerged, driven by two decisive phenomena: dramatic socio-political circumstances and the opposition between the modern and the ancestral. From reflection on themselves and their existential condition, disturbing perspectives on identity as subjects and inherited notions emerged.

In Chile, in the analysis of interculturality, Zuchel and Leiva (2020) in their research, the objective was to show examples of how interculturality is manifested from a critical perspective and, some questions were raised that challenge the notion of the "inter", seeking to revalue the conflict, explore its causes and promote a historical praxis of liberation. The result was the analysis of interculturality in Chilean education, which is absent, but demanded. The PRs must prioritize social demands to ensure a society without asymmetries. Diversity is an undeniable fact, as confirmed by international reports. While multiculturalism policies have been implemented that show a willingness to be inclusive. It is important to recognize that interculturality goes beyond simply incorporating the "other" into the dynamics of countries. It is necessary to ensure that everyone has the same opportunities and rights that endorse critical interculturality. Whereas interculturality as a political and ideological principle has emerged through the struggles of indigenous and Afro-American movements since the 1990s.

In Colombia, Martínez-Ruiz (2019) developed a study based on hermeneutic phenomenology in a rural educational institution with the aim of analyzing the experiences of children through hermeneutic phenomenology to identify the emergence of their identities. The result was the visibility of the children's identity through their experiences in their home and community, in interviews, storytelling and painting workshops. In the conclusion, he said that identity and territory are related in the experiences of children and influence their mission and personal vision. Rural schools urgently require the support of MINEDU.

Finally, in the context of Chile, Mora-Olate (2019) in his research indicated the objective of analyzing the contributions of Latin American intercultural philosophy in schools; through a literature review. As a result, interculturality in Latin America must promote a pedagogy that recovers contextual knowledge in the process of the universalization of humanity. The conclusion, the CI recognizes cultural diversity through pluralism and cultural identity.

Likewise, in the research, ontological, epistemological, and axiological assumptions underpinned the theoretical framework of the research. In the research, the ontological assumptions in times of the bicentennial of Peruvian independence, the PERs and the CI require the visibility, understanding and confrontation of the patterns of domination, exclusion, asymmetries and conflicts that occur in intercultural spaces (Arroyo et al., 2020) in rural areas, mainly.

Epistemological assumptions are based on the interaction of different cultures in the same space, a process that favors the economy, but increases actions of racism and discrimination (Gutiérrez, 2020). The heterogeneity of people and their native culture requires respect for the differences between students and teachers where students and teachers interact and participate in scenarios of reflection and proposals in the face of structural situations of a state. In Peru and Apurímac, interculturality is considered as a project to strengthen equity and identity in a multicultural society (Campos, 2019). Therefore, CI must be an ethical and transformative project in the face of structural cultural and economic inequalities in countries where multiculturalism is evident. Therefore, the best space to promote CI is education, where it should be considered as a principle of the PER.

In axiological assumptions, the presence of the "other" is the presence of cultural diversity that involves everyone in an educational institution. The curricular activities that take place in schools and colleges help integration between minority and majority groups, and this occurs spontaneously. However, in these contexts, the construction of identity does not involve procedural aspects but rather internal legal frameworks that guarantee the fundamental rights of all under equal conditions, as an exercise of differentiated and active citizenship (Correa & Guzmán, 2019).

Regarding the theories that supported the research, on PERS; national education policies (NSPs) are related to poverty and inequality that affect access to secondary education (Gluz et al., 2020). Also, De la Cruz-Flores (2022) analyzed the problems of educational policies and their link with educational equity in Latin America. So, it is important to mention that EPs are often addressed superficially, without an in-depth analysis of the underlying causes of the problems they seek to solve (Villagómez & Llanos-Erazo, 2020).

In the context of Peru, the National Educational Project (PEN) is presented as a public policy instrument that encompasses all sectors and levels of government. This project establishes the medium- and long-term strategic guidelines for achieving educational objectives in the country. Its objective is to move towards a society that guarantees full citizenship, which implies the full development of each individual and the progress of a democratic collectivity (CNE, 2020).

And in the Apurimac region, the PER (regional educational project) is a guiding instrument to materialize the educational vision in the Apurimac region. This document details the educational priorities to be followed and establishes the direction that will guide regional educational development from the year 2022 to 2036. It is a strategic framework that regulates educational policy in Apurimac and is mandatory at all governmental and social levels. This document is the basis for political decision-making in the region, allowing for clear and continuous planning towards the year 2036 (DREA, 2022). In the research, the definition of the PERs was assumed as the guidelines and actions to be implemented in the educational system of a specific region to guarantee a full citizenship of the person.

Regarding CI, Tubino (2005) is the educational approach based on critical-liberating interculturality that is considered dysfunctional or not in accordance with the current societal model. From this perspective, interculturality and citizenship are intrinsically related and cannot be dissociated. The CI prioritizes the formation of citizens who safeguard a multicultural democracy that includes and values diversity in our country.

Walsh (2009) adds that the approach and practice of CI do not align with the current societal model, but rather seriously question this model. The CI addresses the problem of power, racialization and difference (not only cultural, but also colonial) that have been constructed from it. While functional interculturalism responds to the interests and needs of social institutions, critical interculturality arises from the experiences of people who have been subjugated and subalternized throughout history. And in the research, CI is assumed as a pedagogical proposal that promotes the decolonization that is built from the original inhabitants to renew knowledge, being, power and life itself; it is evidenced in collaborative work through the use of the Quechua language and with the practice of ancestral values in a globalized context

After developing the different definitions in relation to the topic of study, two categories were considered, the PERs and the CI. Regarding the PERs, Pita (2020) points out that they must be planned and considered as a cross-cutting principle to achieve quality education. These policies could be a solution to educational and social problems, as well as being adequate to meet the needs and demands of populations that feel discriminated against by the State. Also, Díaz and Vargas (2020) in their research, state that educational policies must guarantee democracy as a social right and must be sustainable.

In the first subcategory, learning for full citizenship, Suasnábar et al. (2018) mention that EPs must be linked to the organizational structure of the State; In addition, Ollivier, (2020) in the context of Latin America indicated that EPs are responses to social demands, however, they incorporate the interests of international organizations that provide support through financing and political decisions to countries. Likewise, the current reality demands the permanent analysis of the processes of interaction between the state, governance and education in order to generate EPs that respond to social demands and the country's development policies in a globalized context, but validating the multicultural reality that must be vindicated.

In the National Educational Project (PEN) 2036, those responsible for the proposal recognize the problem of cultural diversity in Peru, as well as the discriminatory attitudes and political decisions that have affected indigenous cultures. In addition, it was observed that there are few opportunities for indigenous people to access an education that allows them to develop personally (CNE, 2020). Therefore, it is advisable to carry out a comparative analysis of educational policies in different regions, considering local, regional and national demands in a globalized context. In the case of the Apurimac region, according to INCORE data, it ranks 15th and in the education indicator, illiteracy among people aged 15 and over is 24th (IPE, 2021). These results should be the subject of a comparative analysis and should be taken into account when making decisions in educational policies.

Regarding the second subcategory, intercultural educating society, Freire and Leyva (2020) emphasize in their research that intercultural education incorporates elements that positively influence education. The efforts of researchers and civil society for intercultural education in Ecuador, even since Paulo Freire's proposals, are still in process, but an example to follow and improve in other Latin American countries.

According to the PE guidelines, the GORE (Regional Government) Apurímac considers educational quality from an intercultural perspective (GORE Apurímac, 2020 - POI 2021-2023, 2020; PEI 2021-2023, 2020). Education is the transcendental pillar for the development of the region and is considered as PE, a quality education that evidences interculturality, the development of science that generates sustainable production (DREA, 2020; DREA, 2015). Therefore, the EPs must be assumed within the framework of the comparative analysis of achievements and gaps in the educational service provided in Apurímac, but it is evident until 2021, the hegemony of the code that is used from the initial educational level to the higher educational level of the Spanish language, in a region where 69.69% of the total population is Quechua speaker (Andrade-Ciudad, 2019). EPs will be successful if they respond to the demands and problems of the social, cultural and economic reality of a region that leads in mineral resources, but still with asymmetries in education.

Regarding the third subcategory, Innovation and research for sustainable productive development, Pacheco-Bohórquez et al. (2020) state that each country has its particularities in the educational system and policies. Thus, Pérez (2020) recognized the contributions of researchers who promoted the universality of education, which is a pillar for decolonization, emancipation, and vindication of identity in Latin America. In Latin America, there is a social demand for decolonization research to ensure a symmetrical dialogue and to plan, execute and implement PE.

The analysis and design determine the improvement of the PERs that must be aligned with realism and must include systematic comparisons of innovations (Fontaine, 2020). And they require comparative analysis for a successful application in kindergartens, schools, colleges and higher education (De Sierra, 2019). As a matter of principle, they must respond to social demands and be evaluated on an ongoing basis. Thus, the DREA, in its management instruments, plans strategies and activities to meet its PEs, but school dropouts and low achievement rates persist (IPE, 2021), mainly in rural schools and colleges, in the census evaluations carried out by MINEDU each school year.

Finally, in the fourth subcategory, participatory and decentralized management, it is important to consider the study by Lazo and Torres (2021) on educational goals in rural Peru during the twentieth century. In their research, they concluded that the educational purposes of the current Peruvian system are designed to consolidate privileges of small power groups that benefit from it, while the educational aspirations of rural Peruvian communities seek to change this system through the active participation of users in a decentralized manner, since they live in situations of exploitation and misery. The majority of Peruvian society faces conditions of exploitation and extreme poverty, which makes it necessary for the PERs to be designed with principles of interculturality (IC) in order to achieve educational advances and true national development that includes, mainly, native cultures.

Considering Carrasco's (2021) research on results-based management in a school in Lima in 2019 revealed that interviewees recognize the importance of results-based planning, but its effectiveness is limited by the insufficient budget allocated by MINEDU. In conclusion, results-based management is considered crucial in EI No. 7073, since it has the planned regulations and management documents, however, it is not reflected in optimal institutional results due to the lack of budget, untrained personnel, scarcity of material resources and delay in training programs for managers and teachers.

Referring to the second category, IC, Walsh and Monarca (2020) refer to the fact that schools, colleges and higher education centres are scenarios of political analysis and decoloniality must be the principle of a real education with CI principles. Also, Mora-Olate (2019) in his research emphasizes the importance of a pedagogy that recovers contextual knowledge in the process of the universalization of humanity. In line with the contributions of Latin American philosophers to cultural diversity. The PERs should consider CI as a philosophical proposal.

The CI makes it possible to analyze the situation of discrimination and exclusion in order to promote a just society, without inequalities and with a mission-vision of a society with sustainable development. In Latin America, Wences-Simón's (2021) contribution in his research on Critical Interculturality referred to the proposal of a symmetrical dialogue. Because the CI is a foundation that establishes the route for a true decoloniality in Latin America that generates development with identity in a global world.

Tubino (2020) expressed that the results show the need to make differences and inequalities visible in Peru. Its important conclusion was, it is urgent to make visible the situation of inequalities and cultural diversity in order to promote plurality. Added to this are the decolonialist proposals that highlight critical reflection on the effects of coloniality in subaltern areas. Likewise, the continuity of colonization and imperialism was confirmed through the coloniality of power, knowledge and being. (Munsberg & Da Silva, 2018).

Continuing with the scientific contributions, Segovia-Quesada et al. (2020) in their research on education in rural areas of Peru. The result emphasizes the practice of resilience to improve educational service and occurs when teachers turn limitations into opportunities to face adversity. Attitude and practice of resilience is necessary in the professional profile of teachers in rural areas. And the CI promotes a reinvention of the State that makes indigenous cultures visible and, in education, guarantees an inclusive multicultural democracy (Tubino, 2005). Thus, CI and EP guarantee quality learning even in university students (Camillo et al., 2020).

In the analysis of CI, Medina and Huamán (2019) state that ancestral knowledge must be recovered and a review-analysis of the theoretical foundations of decolonial CI must be carried out. In addition, research and consider ancestral knowledge in the educational curriculum. And Segovia-Quesada et al. (2020) state that current educational programs do not respond to rural reality and even less consider the implementation of resilience actions.

The first subcategory of critical interculturality in Apurímac, according to Catherine Walsh and Fidel Tubino, refers to a pedagogy and praxis of critical interculturality that promotes decoloniality (Walsh, 2009) mainly in contexts where people have been victims of subjugation (Walsh, 2010). Thus, CI promotes the training of people who build an inclusive multicultural democracy (Tubino, 2005) to guarantee quality education in a multicultural context. Likewise, Aguerre (2020) in his research endorsed the proposal of the implementation of intercultural universality in opposition to colonialist universality.

Likewise, Sanchez (2021) in his research determined the importance of the demand for the analysis of the reality of Latin American countries and the process of decolonialism. Decolonialism is a beginning for the reengineering of EPs in multicultural contexts because it guarantees symmetries in dialogues with indigenous cultures. In an analysis of the CI, Medina and Huamán (2019) state that interculturality with a decolonial approach does not exist to date, even in Ecuador and Bolivia. The recommendation is to recover ancestral knowledge and carry out a review-analysis of the theoretical foundations of CI.

In the second subcategory of Multilingualism, Tubino (2019) emphasizes that interculturalism must be implemented as a dignifying practice for harmonious coexistence. Because to date there is a multidimensional inequality that harms the original inhabitants in demonstrating their competencies and exercising their rights because they are stigmatized because of their Andean origins or the accent of the Quechua language in their expressions compared to people who speak with an English accent, which disqualifies them in job interviews; and it is urgent to make these inequalities visible in order to promote plurality (Tubino, 2020). Inequalities and cultural diversity in Peru are interrelated and it is the task of all Peruvians to analyze, reflect and propose for a true experience of multiculturalism that includes multilingualism.

Historically, since colonial times, the implementation of pedagogical strategies for education has led to the application of an evangelizing model with clearly established elements: the recognition of the value systems of the time, the study of aboriginal languages to achieve the goals of the model, but above all, the legitimate implantation of political power. economic, socio-cultural. The alternative towards an education with educational and cultural inclusion leads to a recurrent criticism of the proposed model, since there are structural elements in the valuation of cultural groups in the education system, such as inequality in access to university linked to economic marginalization and discrimination (Tipa, 2018).

The general theories of CI and PERs that affirm the interrelation of these in education in rural areas. Vygotsky's sociocultural theory, which states that learning is generated and achieved in spaces of interaction because learning and work in contexts of interaction always add up to the benefits and achievements of organizational goals (Ozturk et al., 2021); therefore, better institutional achievements (Gerstenberger & McCarthy, 2020). People are social by nature and it is from this space that EP proposals must be generated to achieve quality education.

Currently, it is necessary for the Peruvian education system to implement interculturality processes in educational institutions as a proposal for improvement (Rivera et al., 2020). Moreover, there is an urgent need for intercultural academics to get to know each other better among teachers and students (Gónzalez Monroy et al., 2020). This creates an environment conducive to exchanging innate experiences of their native cultures and strengthening the effectiveness of the PERs. The opposite of interculturality refers to the exclusion or differences that exist in classes (Delbury, 2020).

METHODS

According to the orientation, type and design of research, the research is of the basic type; it aims to achieve new knowledge (Álvarez-Risco, 2020) and is important for its applicability with practicality (Gonzales, 2022) in the study of contextual phenomena. The research approach is qualitative because it "examines how or why a phenomenon occurs (Maturrano, 2020). The type of research made it possible to meet the objectives determined in the research. Thus, the research design was hermeneutical phenomenological, considering its objective of revealing the phenomenon in its essence in order to analyze and validate it scientifically (De Salas, 2020). In the present research, it was possible to analyze the phenomenon under study.

In the research, the categories are: (a) regional educational policies and (b) critical interculturality. Conceptual approaches to research that include CI and PERs characterize the thematic unit. CI is a proposal to promote decolonization and the critical emancipation of the person in an intercultural context (Lisboa et al., 2020). It is the demand to vindicate the inhabitants of native cultures to revitalize their culture and the best option is the real implementation of the PERs that include the CI. In addition, the PERs must guarantee efficiency in the educational service to train people who are free and successful in society (Bentancur, 2021), the educational service to which people have access to develop their capacities in strict compliance with their rights.

Likewise, in the research, the study scenario covers secondary level educational institutions in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Abancay; It includes the districts of Tamburco, Curahuasi, Cachora, Huanipaca, Pichirhua, Lambrama and Circa. All districts have rural areas and semi-structured interviews and observation guides were applied for the study in the last 6 districts in rural schools. As can be seen in Figure 1 found in Annexes.

The study population will consist of specialists, directors, teachers and students of the secondary education level from rural areas of the UGEL Abancay. The sample was selected according to the role they play in rural secondary education in the province of Abancay. The sample consisted as follows: (a) 4 specialists from the Apurimac DREA, (b) 3 specialists from the Abancay UGEL at the secondary level, (c) 6 teachers from the rural education of the EBR, secondary education, (d) 6 principals and (e) 6 students from the secondary education level from rural areas of the province of Abancay.

The data collection techniques were: (a) interview, through the instrument, semi-structured interview guide that allowed the interrelation of the interviewer with the interviewee, (b) documentary analysis for the collection of data from scientific articles and books, being its instrument, the documentary review sheet (c) observation to collect information about the study phenomenon through the non-participant observation guide.

The procedures carried out were: (1) Definition of the research problem, where the problem is defined to develop the research project, (2) The research was carried out, (3) The instruments were validated, semi-structured interview guide, non-participant observation guide and the documentary review form, (4) The research instruments were applied to collect the corresponding information, (5°) The systematization of the data through the ATLAS software. 23 of the interviews, non-participant observations and the documentary review sheets that are framed in the results (figures), (6) The discussion after having the results defined the problem and responded to the specific objectives of the research through the analysis and interpretation of each figure, (7) The conclusions and recommendations so that they can be considered in future works and (8) The proposal that can generate improvements in the the problem identified.

Scientific rigor assumes of Noreña et al. (2012) who states that qualitative research must guarantee scientific rigor throughout the process, for which it must assume the following: Reliability and validity, which are essential characteristics that the scientific tests or instruments used to collect data must possess. (Noreña et al., 2012). Credibility as a value of truth or authenticity. Transferability as applicability. Consistency or dependency as replicability. Confirmability or reflexivity known as neutrality or objectivity. Relevance makes it possible to assess whether the set objectives were achieved. The theoretical-epistemological adequacy or concordance must be considered from the beginning when working with qualitative methodology, mainly.

The data analysis method was the ATLAS.ti 23 software, a tool that allowed the systematization, analysis and interpretation of data collected through the instruments.

The ethical aspects are evidenced by the fact that this study was carried out in strict compliance with the ethical principles: respect, justice, responsibility, honesty and justice. The international and national criteria framed in the use of the APA Standards, seventh edition to guarantee the quality of the research that requires authors to respect through the corresponding citations and references. Likewise, the study was based on the ethical principles of the Code of Ethics at César Vallejo University (RCU No. 0340-2021/UCV, 2021).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

According to the data collection through the instruments applied, which were: semi-structured interviews, non-participant observations and documentary review sheets; the results were as follows:

Figure 1. Phenomenon and subjects of research

Note: The phenomenon studied was PERs and CI.

From the collection of data from 4 specialists from the DREA, 3 specialists from the UGEL Abancay; 6 directors, 6 teachers and 6 students from rural areas of the province of Abancay using the ATLAS.ti 23 software, taking into account the descriptive analysis of each item, among them were developed according to the categories and subcategories of the research. The results are presented according to the objectives set. Considering the general objective: To analyze the PERs and CI in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023.

Table 1 showed the importance of the clamor of native populations in the use of their language during the educational process and to date there is no evidence of CI actions in the PERS. Educational actors recognize the importance of CI in the PERs, for example collaborative work through the use of the Quechua language and with the practice of ancestral values in a globalized context. This is validated in the result by ATLAS.ti in figure 2.

|

Table 1. Link between PERs and CI in schools in rural areas of Abancay |

|||

|

General Objective |

Techniques |

||

|

Semi-structured interview |

Non-participant observation |

Documentary review |

|

|

To analyze the PERs and CI in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023. |

Answers related to the link between the PERs and CI, in the text of the PER the use of Quechua is considered and in the II.EE. Its implementation begins with shortcomings |

Responses related to the link between the PERs and CI, in the text of the PER the use of Quechua is considered and in the II.EE. it is not implemented. |

Responses related to the link between the PERs and CI, in the text of the PER the use of Quechua is considered and in the II.EE its implementation is urgent. |

|

Responses related to the demands of the implementation of CI in the PERs |

|||

|

Note: CI is a demand that must be implemented in the PERs to serve indigenous populations. |

|||

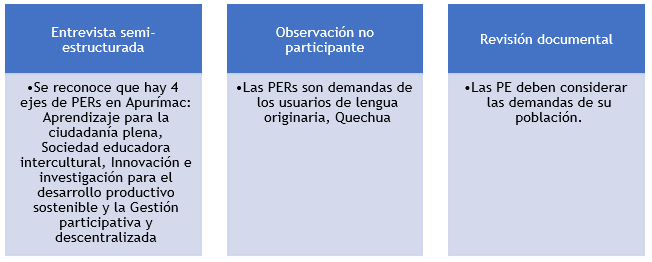

Figure 2. PERs in rural schools in Abancay

Note: The PERs in Apurimac include 4 strategic axes for the improvement of student learning (DREA, 2022).

In the results of the application of instruments, the axes of the EP in rural areas that are also the subcategories are: (a) Learning for full citizenship that includes actions of inclusion and affective treatment, development of student competencies, student protagonism, Promotion of the intercultural and productive regional curriculum, implementation of materials and equipment to improve student learning, revaluation of teachers. The second sub-category, (b) Intercultural educating society that is evidenced in actions of citizen participation, community education, recognition of the culture of the region through research, integration of ancestral knowledge and potentialities of the communities; in the third sub-category (c) Innovation and research for sustainable productive development, it is observed in facts of quality higher education, recognition of research and innovations, promotion of entrepreneurial skills, good teaching practices, conservation of Quechua. In the fourth sub-category: Participatory and decentralized management, decentralized management actions must be observed and practiced through the use of Quechua, the promotion of attention to vulnerable students (use of Quechua), the motivation and recognition of improvement actions.

Finally, Specific Objective 2: To describe critical interculturality practices in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023.

Figure 3. CI internships in rural schools in Abancay

Note: CI is mentioned in the Apurimac PER to 2036.

The results show the low implementation of the PERs, despite the fact that the CI includes 2 sub-categories; Critical Interculturality in Apurimac that is observed in actions of critical interculturality that consists of collaborative work through the use of the Quechua language and with the practice of ancestral values in a globalized context, the promotion of actions to implement the Apurímac PER, published in 2022, the generation of actions to improve the academic performance of Quechua-speaking students. In the sub-category of Multilingualism, the promotion of the use of the Quechua language, the support for language learning and interaction in the Quechua language should be appreciated.

DISCUSSION

After reviewing the results of the semi-structured interviews, non-participant observations, and documentary review sheets, it was shown that in relation to the general objective of analyzing regional educational policies and critical interculturality in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023, In most of the responses, responses of ignorance of the current PER and HF predominated, even more, but activities are carried out that include the use of Quechua, although there are shortcomings on CI strategies. Students demand the implementation of CI activities without knowing the concept. The PER Apurimac does not carry out its purpose in serving Quechua-speaking students. Even more so, if the culture of the natives is considered as a collaborative work through ayni, mink'a, but always using Quechua and respecting ancestral values such as respect, solidarity, empathy, assertiveness, among others.

The PERs must be contextualized to the reality of the students (Fontaine, 2020), mainly from rural areas, because these young people use their language 1, which is Quechua, in their interactions. Likewise, CI enables the practice of ancestral values (Aguerre, 2020), situations that strengthen students' competencies (Camilo et al., 2020). And considering that teachers disseminate intercultural practices such as the preservation and use of native languages, but strategies to disseminate L1 (language 1) and L2 (language 2) need to be strengthened (Cépeda et al 2019). And Pacheco-Bohórquez et al., (2020) considered that EPs require greater economic investment and articulation with institutions and society; to which, Casadellà et al. (2022), that education must be done to imagine desirable futures and thus guarantee sustainable development; to this, Suasnábar et al. (2018), that the knowledge of students that generates enriching learning should be included.

Although, in Peru, public education is in crisis due to political causes and the education system (Canaza-Choque, F. A. (2022); therefore, information on its progress and setbacks should be reported to the public for contributions and suggestions for its improvement (Santos & Alencar de Medeiros, 2020). For example, Apurímac, in 2021 (IPE, 2021), ranked 23rd out of the 25 regions in the education index in the INCORE (regional competitiveness index); and in 2022, 19th place (IPE, 2022), but 24th place in illiteracy.

It is urgent to recognize that cultural traditions favor educational improvements (Tram et al., 2021), to which inclusion is added as a purpose (CNE, 2020) in the formation of values and social responsibility that strengthen EPs (González et al., 2022). However, it is necessary to take action so that education is not an instrument for politics and the essence of integral formation must prevail (Hodgson, 2020). And interculturality encompasses political and epistemic aspects by working for harmonious coexistence and an improvement in the transformation of society and the State. In this sense, the educational institution is committed to strengthening its strategies to form tolerant citizens who are open to diverse identities. The benefits of integrating interculturality and law, which is reflected in strategies aimed at rethinking the coexistence between diverse individuals (Correa and Guzmán 2019).

Likewise, Gutierrez (2022) indicated that the implementation of critical and intercultural education depends on educators committed to building a better society. To this end, teacher educators must be aware of adopting a more critical and intercultural perspective through the analysis of forms of oppression and being oppressed, new forms of oppression and new ways of contributing to the construction of a more just society. And that, instead of indoctrinating or homogenizing the understanding of the world, we should explore the multiple perspectives that converge in the classroom and in the texts. This openness is relevant for both educators and teacher educators because behavior-examples have a significant impact on future teachers.

The contributions of González-Monroy et al. (2020) on the intercultural curriculum that requires local educational communities and their members to know themselves, because this is essential for the formation of a strong identity. And when the population went through armed clashes, it is essential to empower the inhabitants to identify with their origin and to value their traditions, customs and knowledge. Regarding the materials for effective critical global teaching, Hazaea (2020) that CI demands, they can be topics such as poverty and climate change to analyze power relations in the construction of global citizenship. Texts can be authentic textbooks or journalistic texts, critical readings that generate creative writing and influence the construction of intercultural meaning. Well-designed intercultural texts are important for promoting mutual understanding and intercultural communication. And to assess intercultural communication, additional tools such as classroom recordings, observations, and semi-structured interviews with students can be employed. In addition, implementing research in multimodal intercultural texts, such as films and social media, can promote critical media literacy and intercultural communication.

One strategy to promote CI is collaborative learning in virtual environments (Lämsä et al., 2021) that should be focused on meta-analysis activities to elevate learning. As well as the development of tools for real-time formative assessments, providing feedback and support to students as they progress in their learning. Therefore, strategies that favor CI should be extended to all populations that have been colonized, subalternized, and excluded (Lisboa et al., 2020). Because these groups seek to be recognized as possessors of cultures and knowledge that are equally valuable to those imposed and legitimized by the West. But, Ozturk et al. (2021) indicated that virtual collaborative work recognizes its importance, but highlights the challenge of promoting strategies for better processes for design students.

In this sense, promoting CI in initial teacher training courses and in the educational curriculum is a political strategy of emancipatory transformation, linked to changes in the social field. To achieve this, it is necessary to promote a process of growth and change of consciousness, where awareness of one's own historical conditions is taken from a critical and dialectical perspective. To achieve this goal, it is essential to confront the divisions that arose from colonialism and to provide an education that breaks with the alienation and omission that perpetuate the division between different forms of knowledge. CI must be implemented in all educational instances to ensure a decolonization of knowledge (Lisboa et al., 2020). In this way, it will be possible to challenge the paradigms of exclusion and discrimination, aspiring to build a more humane and ethical society.

And it is necessary to mention Medina and Huaman (2019), who endorsed the approach of interculturality that includes all populations that have been colonized, subordinated and excluded, seeking to value their own cultures and knowledge. At present, there is a "coloniality of power", where economic and social domination is imposed by external capitalist countries. However, the examples of Bolivia and Ecuador, which were presented as successful CI experiences, have been belied by the persistence of extractive practices and corruption in government. It is difficult to find a political group that guarantees the implementation of this decolonial intercultural policy, due to the adversities of the real conditions. Then, they raised the need to review the theoretical foundations of decolonial CI and consider a broader and more integrative vision that values and recovers both ancestral knowledge and scientific knowledge for the benefit of society. In this regard, Munsberg and Da Silva (2018) indicate that the "decolonial inflection" or "decolonial turn" represents an essentially epistemic change that questions Eurocentric modernity and proposes an "other episteme" based on pluriversality. It is a political project that goes beyond understanding the logic of coloniality from a different point of view. Its objective is the decoloniality of power, knowledge and being as resources to build an alternative thought. The members of GM/C (Modernity Coloniality Group) believe that decoloniality is the path to interculturality.

GM/C see CI as a political, social, ethical, and epistemic strategy to transform the reality of Latin America and societies subalternized by modernity/coloniality, especially in the field of education. Because the continuity of colonization and imperialism through the coloniality of power, knowledge, and being is recognized, and the main contribution of the epistemic project from a "decolonial" perspective is highlighted. Thus, it was concluded that PERs and CI are necessary phenomena in the education provided in rural schools in the province of Abancay. This was shown in figure 4.

Figure 4. CI and PERs in rural schools in Abancay

Note: The CI is a demand that must be implemented in the PERs to serve students from rural schools in Abancay.

In relation to the first specific objective of identifying regional educational policies in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023, it was shown that the PERs in the region of Apurímac have been published in 2022 in order to ensure that men and women should receive practical teachings in the community during their lives. with ancestral foundations of good living, entrepreneurship (DREA, 2022; Zambrano et al., 2020; MINEDU, 2019; Flores et al., 2020; Garcia, 2015; García-Cconislla, 2020; Rafael & Orbegoso, 2019). In this regard, Arroyo (2020) indicates that EPs must articulate with interculturality to put an end to asymmetries in education.

Díaz-Guillén and Vargas-Monzón (2020) also endorsed that education is a right that must guarantee democracy and the sustainable development of a society. Moreover, CI would emancipate EPs in colonized schools (Mora-Olate, 2019), with resilient teachers who change limitations into strengths (Segovia-Quesada et al., 2020). Even in migratory situations, the role of the inclusive teacher favors EPs and interculturality (Jiménez-Vargas, 2022). Thus, the PERs in secondary education in rural areas of Abancay are: (a) Learning for full citizenship, (b) Intercultural educating society, (c) Innovation and research for sustainable productive development and (d) Participatory and decentralized management (DREA, 2022) (figure 5).

Figure 5. The PERs in rural schools in Abancay

Note: There are 4 PERs in rural schools in Abancay.

In relation to the second objective, To describe critical interculturality practices in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023, it was shown that teachers and principals make efforts to plan and execute interculturality activities, but on CI, as collaborative work through the use of the Quechua language and in the practice of ancestral values in a globalized context, It is poorly applied due to a lack of knowledge of the relevant strategies. There are efforts to use Quechua in schools, but it is not enough to meet the demand of native students. The DREA has not sent the texts of the PER Apurímac and the UGEL Abancay to the schools, nor has it carried out dissemination activities. This is shown in Figure 12.

Considering the contributions of Freire and Leyva (2020) as background, intercultural education has incorporated several elements that influence educational practice, such as the identification of relationships between different factors and educational reality. In addition, Albertsen and Zuchel (2019) refer to interculturality as an experience that constantly drives us to open up to other realities that move and transform us, generating a life in constant evolution and renewal in time and space. They considered the philosophy of the Mapuche people because it questioned and challenged transcendent rationality and Western reason, which allowed them to think from the relationship with others and recognize the diversity in the way of living and perceiving life and the world.

And Hauerwas et al. (2021), recognized globalization as a demand to act for a critical global teaching that must begin in teacher training that is inclusive and fair in a global context. A teacher with solid training and collaborative work praxis (Bravo, 2020; Rojas, 2020; Aparicio and Sepúlveda, 2019; Quispe, 2020) will generate significant learning in students (Mellado & Chaucono, 2019; MINEDU, 2019; MINEDU, 2014; MINEDU, 2012). Even more so, in difficult times, such as the 2023 school year, where there is a social demand for the mediating role of the teacher (Llorente & Topa, 2019) in accompanying students so that they are competent in resolving problematic situations in favor of a sustainable society. Proposals that validate the implementation of the PERs, which to date have not been implemented.

It is necessary to include the contributions of Comboni-Salinas and Juárez-Núñez (2020), who refer to the term "interculturality", where the prefix "inter-" implies a relationship between two or more people, groups, among others. In a broad sense, they referred to the relationships between humans, their groups and institutions through various products, whether material, social or symbolic, which include values, ideas, beliefs and rituals learned, transmitted and socially modified, including presentations in the digital sphere through the internet and other media. Thus, interculturality encompasses a wide range of relationships and encounters between different cultures and social groups.

In addition, Abba and Streck (2019) indicated that CI broadens the reflection on internationalization by placing it in a broader context of social and cultural processes in heterogeneous societies. And it is an alternative to the hegemonic internationalization of education, allowing us to understand contemporary challenges and the opportunity for dialogue and understanding with others in multicultural contexts (figure 6).

Figure 6. CI in rural schools in Abancay

Note: CI is a challenge for teachers and administrators, but for students it is an educational necessity.

Considering the contributions of Rivera et al. (2020) on cultural diversity, which should be considered as a generalized characteristic and not an exception. That seeks a quality education that fosters civic education, meaningful learning and social values in search of good living, regardless of the different cultural practices present.

Currently, the most appropriate educational model to promote meaningful learning in a context of cultural diversity is the intercultural approach, based on inclusive or intercultural pedagogy. To achieve this, it is necessary to make modifications to curricular content, encourage attitudinal changes in communication and interaction with others, and adopt new methodological strategies to facilitate meaningful learning. In this regard, Sanchez (2021) indicated that decolonialism allows us to empirically address the various types of interpellation of living human materiality, such as oppression and exclusion in peripheral countries.

In this regard, Tipa (2018) reproaches the intercultural model taught in the university, where professionals are trained, there is a lack of consolidation of the intercultural discourse between careers, teachers and academic administration. This requires attention from the academic administration, through training for teachers and workshops on interculturality and its practical application, Thus, Tubino (2020) referred to social asymmetries generate elites that monopolize the opportunities to access quality services and exercise fundamental rights. At the same time, they exclude the vast majority from being able to exercise those rights that are legally recognized to them. In this context, Walsh (2009) proposes a pedagogical approach based on humanization and decolonization, that is, on the process of re-existing and re-living as forms of re-creation.

Also, Walsh and Monarca (2020) defend the urgency of implementing decoloniality to create situated and contextualized spaces that open up to the pluriversal. There, decolonial pedagogy and praxis must be grounded in a detailed analysis of how patterns of colonial power operate in concrete contexts and how to create different conditions. Paying attention to the cracks and the fabric where the threads intertwine without melting. And Wences-Simon (2021) strengthens it by stating that dialogue in a CI framework with a decolonial approach is key to the real progress of Latin American peoples and to renounce one's own thinking, maintaining a constant critical self-reflection on one's own ideas and values.

To strengthen the implementation of CI, Perez (2020) proposed the practice of ancestral values that would contribute to current scientific knowledge, which had its origin in political-social circumstances and the tension between two cultural horizons: the modern and the ancestral. Then, the demand for CI in education was ratified because it facilitates the search for universality and authenticity, offering fundamental elements for epistemic decolonization and the process of emancipation and vindication of one's own memory and recognition in today's world. And as a strategy to strengthen CI during teaching, Wang et al. (20219) indicate that the inclusion-relationship of culture and language through PBL (project-based learning) from a multilingual perspective and that allows understanding the critical moments of intercultural encounters is efficient in language learning. Gutierrez (2022) adds to the proposal, referring to the fact that teacher training must consider the critical and intercultural perspective that multiple identities affirm, through the analysis of contradictions that are observed in reality. Understanding the multiple perspectives that converge in texts and in the interactions between people are essential to avoid indoctrination. It is a demand and challenge for both future teachers and teacher educators.

But, Susilo et al. (2023), refer to the importance of the development of critical intercultural awareness through video clips that generated the in-progress formation of intercultural critical awareness (CIA) in higher education students. Thus, the use of culturally appropriate YouTube video clips with intercultural tasks promotes the development of skills to identify, interpret and critically evaluate the intercultural values present in the clips, a strategy applicable in the reality of rural schools in Abancay. And they reinforce Arias-Gutierrez and Minoia's (2023) proposals on decoloniality and CI in Higher Education because the struggles for decolonization address the problems of knowledge coloniality that persist in postcolonial states and affect their national educational programs. In its most radical form, the CI seeks to represent and revitalize knowledge and languages that have long been made invisible and erased. Likewise, culturally relevant education would reduce the epistemic gap that affects access and retention of indigenous students, especially in higher education.

CONCLUSIONS

First: According to the general objective, general objective of analyzing regional educational policies and critical interculturality in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023, it predominates that the PERs of Apurímac do not implement CI strategies, only one paragraph in the document points out. The educational community of rural schools is unaware of the current PER, but native students demand the vindication of their language in educational and social processes.

Second: In accordance with the first specific objective, which is to identify regional educational policies in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023, the PER document shows: (a) Learning for full citizenship, (b) Intercultural educating society, (c) Innovation and research for sustainable productive development and (d) Participatory and decentralized management; but unknown by the educational community due to lack of dissemination of the DREA and UGEL Abancay.

Third: According to the second specific objective, to describe the practices of critical interculturality in secondary education in rural areas of the province of Abancay, department of Apurímac, 2023, it is shown that teachers and principals make efforts to plan and execute interculturality activities, but on CI, as collaborative work through the use of the Quechua language and in practice of ancestral values in a globalized context, It is poorly applied due to a lack of knowledge of the relevant strategies. There are efforts to use Quechua in schools, but it is not enough to meet the demand of native students. The DREA has not sent the texts of the PER Apurímac and the UGEL Abancay to the schools.

RECOMMENDATIONS

First: The entities of the DREA and the UGEL Abancay must disseminate the current PER, their strategies to better serve the native students who demand the vindication of their language in educational and social processes.

Second: The regional educational policies of Apurimac published in 2022 must be analyzed in workshops of directors, teachers and students for their implementation in the management instruments of the schools such as: PEI (Institutional Educational Project), PCI (Institutional Curricular Project), PAT (Annual Work Plan) and successively in the AP (annual programs), UA (learning units or learning experiences) for a real planning and execution of the educational process with guidelines of the PERs and therefore of CI.

Third: Teachers and directors should carry out planning workshops under the technical assistance of specialists from the DREA and UGEL to discuss the strategies to be implemented on CI as collaborative work through the use of the Quechua language and in practice of ancestral values in a globalized context, it is little applied due to lack of knowledge of the relevant strategies.

REFERENCES

1. Abba, M. J., & Streck, D. R. (2019). Interculturality and Internationalization. SFU Educational Review, 12(3), 110-126. https://doi.org/10.21810/sfuer.v12i3.1020

2. Aguerre, L. (2020). Intercultural Hermeneutics: From Classical Critique to the Coloniality/Universality Link. Intercultural Hermeneutics, 34, 17-44. https://digital.cic.gba.gob.ar/handle/11746/10784

3. Albertsen, T., & Zuchel, L. (2019). Contributions to intercultural philosophy from a critical review of the concept of Mapuche Rakiduam. Veritas, (43), 69-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-92732019000200069

4. Álvarez-Risco, A. (2020). Classification of Investigations. University of Lima. https://acortar.link/vB0vfN

5. Álvarez-Risco, A. (2020). Justification of the Research. University of Lima. https://acortar.link/KIfxuD

6. Amado DPA, Diaz FAC, Pantoja R del PC, Sanchez LMB. Benefits of Artificial Intelligence and its Innovation in Organizations. AG Multidisciplinar 2023; 1:15. https://doi.org/10.62486/agmu202315.

7. Amaya, L. F., DávilA, J.C., Jara, H.V., & Murcia, L.K. (2022). Hermeneutical phenomenological method. University of Santo Tomas. https://acortar.link/VH0T0j

8. Andrade, L. (2019). Ten news stories about Quechua in the last Peruvian census. Letras (Lima), 90(132), 41-70.

9. Aparicio, C., & Sepúlveda, F. (2019). Collaborative Teacher Work: New Perspectives for Teacher Development. International Journal of Social Science Research, 15(1), 109–133. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-35392019017926

10. Arias-Gutierrez, R. I., & Minoia, P. (2023, January). Decoloniality and critical interculturality in higher education: experiences and challenges in Ecuadorian Amazonia. In Forum for Development Studies, 50(1), 11-34). https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2023.2177562

11. Arroyo, A., Giraldo, C. M., & Guerra, J. C. (2020). Youth Political Subjectivities and Critical Interculturality. Universitas, Journal of Social and Human Sciences, (32), 175-192. https://doi.org/10.17163/uni.n32.2020.09

12. Batista-Mariño Y, Gutiérrez-Cristo HG, Díaz-Vidal M, Peña-Marrero Y, Mulet-Labrada S, Díaz LE-R. Behavior of stomatological emergencies of dental origin. Mario Pozo Ochoa Stomatology Clinic. 2022-2023. AG Odontologia 2023;1:6-6. https://doi.org/10.62486/agodonto20236.

13. BDPI Database of Indigenous or Native Peoples. (2013). Quechua. BDPI. https://acortar.link/bwqDuQ

14. Bentancur, N. (2021). The "right to education" as a new stellar concept of educational policies in Latin America. [presentation]. Ibero-American Congress of Education: Goals. Buenos Aires, Argentina. https://www.chubut.edu.ar/descargas/secundaria/congreso/METAS2021/R1327Bentancur.pdf

15. Bravo, A. M. C. (2020). Collaborative teaching work and its impact on pedagogical management. Science and Education, 1(1), 19-24. https://doi.org/10.48169/Ecuatesis/0101202002

16. Caero L, Libertelli J. Relationship between Vigorexia, steroid use, and recreational bodybuilding practice and the effects of the closure of training centers due to the Covid-19 pandemic in young people in Argentina. AG Salud 2023;1:18-18. https://doi.org/10.62486/agsalud202318.

17. Camillo, J. G. H., Cueva, F. E. I., & Vargas, I. M. (2020). Cooperative work and meaningful learning in mathematics in university students in Lima. Educação & Formação, 5(3), 1-13. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7718955

18. Campos, E. M. (2019). Perspective of critical interculturality in early childhood education. [Master's thesis, Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios]. CUMD Institutional Repository. https://repository.uniminuto.edu/handle/10656/7968