Categoría: Arts and Humanities

ORIGINAL

The role and place of Ukraine in modern international information policy: modern challenges and strategic imperatives of cooperation

El papel y el lugar de Ucrania en la política de información internacional moderna: retos actuales e imperativos estratégicos de la cooperación

Andrii Liubchenko1

![]() *, Volodymyr Коzakov2

*, Volodymyr Коzakov2

![]() *, Svitlana

Petkun2

*, Svitlana

Petkun2 ![]() *, Oleksandr Ignatenko2

*, Oleksandr Ignatenko2 ![]() *, Roza Vinetska2

*, Roza Vinetska2

![]() *

*

1Law Office. Kyiv, Ukraine.

2State University of Information and Communication Technologies, Department of Public Management and Administration. Kyiv, Ukraine.

Cite as: Liubchenko A, Коzakov V, Petkun S, Ignatenko O, Vinetska R. The role and place of Ukraine in modern international information policy: modern challenges and strategic imperatives of cooperation. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2024; 3:1131. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf20241131

Submitted: 07-02-2024 Revised: 18-05-2024 Accepted: 02-08-2024 Published: 03-08-2024

Editor: Dr.

William Castillo-González

![]()

ABSTRACT

Introduction: the relevance of the study is determined by evident and paradigmatic change of global political landscape and corresponding international and nation-state information policy. At the same time, attention is drawn to the presence of theoretical gaps in defining the definition of “information policy”, its institutional structure, as well as the mechanisms for its formation and implementation in today realities, in particular against the backdrop of Russia-Ukraine war and challenges concerning the role and place of Ukraine in international information landscape of international relations.

Objectives: the article aims to develop an array systematizing the processes taking place within Ukrainian media space during the war, which would allow comprehending them based on theoretical paradigms and today realities of information policy, information landscape, and information geopolitics.

Method: the methodological basis for considering research problems is based on the methods of systemic, structural-functional and institutional analysis. The research combines the methodological achievements of several paradigms, constituting the basis of philosophical pluralism - the synergistic method and the paradigm of nonlinearity.

Results: the political role of the information space in modern society and public policy is comprehended. This role lies in the ability of the information space to reflect and subsequently change social processes (including political processes), as well as the interests of the actors dominating the political process. The negative effects of populism in the information policy of Ukraine and the discrepancies between internal and external media narratives are noted. The increasing role of civil journalism and Telegram channels in the information field of Ukraine is shown and an understanding of the corresponding challenges for information policy is proposed.

Keywords: Information Policy; Geopolitics; Citizen Journalism; Information Space; Narratives.

RESUMEN

Introducción: la relevancia del estudio viene determinada por el cambio evidente y paradigmático del panorama político mundial y de la correspondiente política de información internacional y de los Estados-nación. Al mismo tiempo, se llama la atención sobre la presencia de lagunas teóricas en la definición de “política de información”, su estructura institucional, así como los mecanismos para su formación y aplicación en las realidades actuales, en particular con el telón de fondo de la guerra entre Rusia y Ucrania y los desafíosrelativos al papel y el lugar de Ucrania en el panorama de la información internacional de las relaciones internacionales.

Objetivos: el artículo pretende desarrollar una matriz que sistematice los procesos que tuvieron lugar en el espacio mediático ucraniano durante la guerra, lo que permitiría comprenderlos basándose en paradigmas teóricos y en las realidades actuales de la política informativa, el paisaje informativo y la geopolítica de la información.

Método: la base metodológica para considerar los problemas de la investigación se fundamenta en los métodos de análisis sistémico, estructural-funcional e institucional. La investigación combina los logros metodológicos de varios paradigmas, que constituyen la base del pluralismo filosófico: el método sinérgico y el paradigma de la no linealidad.

Resultados: se comprende el papel político del espacio informativo en la sociedad moderna y en las políticas públicas. Este papel reside en la capacidad del espacio informativo para reflejar y posteriormente cambiar los procesos sociales (incluidos los procesos políticos), así como los intereses de los actores que dominan el proceso político. Se señalan los efectos negativos del populismo en la política informativa de Ucrania y las discrepancias entre las narrativas internas y externas de los medios de comunicación. Se muestra el creciente papel del periodismo civil y de los canales de Telegram en el ámbito informativo de Ucrania y se propone una comprensión de los retos correspondientes para la política informativa.

Palabras clave: Política Informativa; Geopolítica; Periodismo Ciudadano; Espacio Informativo; Narrativas.

INTRODUCTION

Information policy pursued by states is a huge complex of tasks and problems, and must constantly adapt to modern society. The interests of society are constantly changing, and due to this, information is becoming increasingly difficult to align to society. In information policy, the process of interaction between the state implementing foreign policy programs and the society at which these actions are directed is important. The information space is growing along with the information society, forming a global process of transformation of the media in accordance with the needs of society. The information provided can influence all major spheres of state life.

The processes of globalization of communication influenced the national and regional doctrines of security and defense, necessitated the creation of a mechanism for solving crisis-related regional problems, in particular, within the framework of the military-political organizations of the OSCE and NATO. Paradigms of international information policy are considered in terms of problems of transformation of foreign policy strategies and diplomatic activity in the conditions of the information revolution, formation of the information economy as a factor of economic growth, implementation of the institutional foundations of international information policy in the conditions of globalization and technological changes.(1)

The latest information and communication technologies (ICT) are increasingly viewed by states as a tool for projecting their power and implementing national interests. Over the past 20 years, the most militarily significant countries have created the doctrinal, logistical and organizational foundations for conducting military activities in the ICT environment, and individual states are already openly declaring the priority of offensive cyber operations, which significantly increases the risks of unintentional escalation. The current situation related to the military-political development of the ICT environment predetermines the urgent need for continuous analysis of current trends in this area and the search for approaches to reducing tensions.

The implementation of information policy is a necessary strategic component for the successful development of a modern state aimed at creating an information society. However, in the landscape of globalization and increasingly complex information connections and flows, patterns of international information policy are of particular importance.

It is now necessary to start developing a global information policy due to the ongoing globalization of knowledge, changes in knowledge creation, the emergence of nonprint formats (such as digital and multimedia), the quick development of wireless technology, and the requirement to share more information and resources. The global information environment will resemble a ship without a rudder in the absence of such a policy. In the broadest sense, the global policy should, at the very least, provide general guidance for the advancement of international asymmetry, free information flow, universal information/library service, and compatible interconnection among telecommunication systems.

The information aspect of geopolitics is becoming increasingly important. Modern experts rightly claim: “by changing information flows within a country, you can change the country.”(2) Indeed, today in scientific and journalistic discourse, there is the concept of “information geopolitics”, a very dangerous phenomenon due to its latency and the effects achieved.

Schiller et al.(3) claim that the geopolitics of information has risen to the forefront of the all-encompassing and progressively contentious debate over who will and how to create the global political economy. The distribution of information resources and communication networks around the globe is a subject of social contestation involving a broader range of individuals as well as political-economic competition between nations and companies. This series is widely defined to highlight social struggles and interstate rivalries, as well as to include emerging pressure spots and surrounding social-historical dynamics.

As one of the key tools of pervasive globalization, information technologies implement the so-called model of “equal (free) access to information” (the call for freedom of information was first put forward by the United States in 1945 at the Inter-American Conference in Mexico City) regardless of the location of the user. Let us note that true freedom presupposes not only equality of participants in this process, but also equal starting conditions, specification of ownership of rights to information, which is a necessary condition for development for the subject participating in it. On the other hand, the model of information freedom can also be used to suppress national media, impose alien opinions, as well as one or another interpretation of historical or current events.

Technologies contain a certain history of their development, ups and downs, an elite, as well as an ‘army’ of associates (the information proletariat), which today is ready for politically active actions.(4,5) In conditions of military conflicts, this social group becomes even more active and is capable of exerting a real influence on national and international information discourse, which is clearly seen in the example of the Russia-Ukraine war. Information waves of discrediting and aggravation of intra-society conflicts of ideological nature are skillfully used by actors in the international landscape, in turn creating the threat of wider spread of geopolitical instability. As Polish political expert G. Kolodko(6) noted, a war fought thousands of miles away resonate with doorstep issues of inflation, local elections, and the pandemic.

It should be noted that the need for the development and applicability of effective forms of international information policy, including political ones, requires the institutionalization and coordination of the activities of national management units, most of which are exposed to the influence of international organizations and TNCs that implement their own policies on the basis of their most powerful financial and organizational resources.(3)

As a rule, the demands of international organizations are aimed at expanding access, while the demands of the countries themselves are more aimed at protecting themselves from external influence. Perhaps this is the result of the defense policy of the past, although today it is clear that the impact in the physical space and the impact in the information space are not identical.

UNESCO sees the goal of information policy as “to give all citizens of a given society the right to access and use information and knowledge”. It emphasizes the benefits to society of such a broad approach: “The benefits of public information may be easier to describe in non-economic terms.”(7) For information produced by governments, perhaps the greatest non-economic value associated with making information available to the public is transparency in government and the promotion of democratic ideals. The more information is freely available from and about government, the less likely it will be that government will be able to cover up illegal activities, corruption, and poor management. On the contrary, excessive secrecy breeds tyranny. The open and unrestricted dissemination of public information also improves public health and safety and overall social welfare since citizens make more informed decisions about their daily lives, the environment, and the future.(8)

These same tasks are described in government documents of Ukraine, like of any other country. The only question that remains open is the real approximation to the formulated requirements. Meanwhile, this issue is extremely important for the future of Ukraine in the community of democratic, dynamically developing states. Therefore, the study of the role and place of Ukraine in modern global information policy seems to be a very urgent scientific task.

Although the term “information policy” was first used by governments to refer to propaganda efforts during World War I, the classical narrow definition of the term includes issues like access to government information. Braman(9) notes that national governments around the world experimented with the idea of creating comprehensive “national information policies” in the 1970s and 1980s. These conversations signaled a dramatic shift in the understanding of the importance of information policy. Information policy was long seen as “low policy” and of little consequence, despite the fact that it sets the stage for all other decision-making, public debate, and political engagement. Only when political leaders realized that rules and regulations influencing information are genuinely matters of “high policy” with broad strategic importance did the idea of a national information strategy become feasible. The shift in perspective signaled by the relatively short-lived discussions over national information policies was durable, and the intensity of information policymaking has continued to expand globally, even though few nations eventually implemented full single information policy packages.

Because of recent developments in data-driven technology, scholars argue that information is more vital to international events now than it has ever been.(10) Each of the four primary functions of information power - influencing other players’ political and economic environments, generating wealth and economic growth, giving one an advantage over rivals in decision-making, and facilitating swift and safe communication - has been completely transformed by these developments.

Today, information is one of the main resources in politics. In the situation of the current balance of power in the international arena, information is a key element of political, economic, and social organizations. The issue of the relationship between the spheres of politics and mass communication is currently one of the most discussed. The most radical idea expressed in this regard is the complete transition of modern politics into the sphere of mass communication.(11)

In the late 1990s, many researchers studied the so-called new “information age.” This period can be characterized by the active development of telecommunication networks, in particular, the spread of the Internet and mobile telephone communications. In addition, developed countries began to develop and implement programs aimed at introducing information technologies into business structures, into the sphere of public administration, and programs also appeared whose task was to incorporate innovative technologies into the lives of citizens.

Since 2000, states have become involved in the designing of “information strategies” for the development of countries. The information dimension has become a new important quality of political planning, which was implemented at the regional, national, and international levels.

In general, the effect of information policy can be divided into three groups of factors.

1. Information communications. They include information infrastructure, the process of informing the public about certain events, facts, opinions (media), the process of the network society functioning and the interaction of its subjects, the provision of computers, mass media, and databases to the population.

2. Informatization of society. This process is structural in nature, because it institutionalizes the spheres of society with the help of information flows: politics, law, education, healthcare, etc.

3. Scientific development of the process of society’ informatization. It implies scientific and technological development of innovations, scientific development and testing, creation of scientific and technological sectors and institutes.

Information policy is also used to modernize today societies and promote comprehensive development of progress. Designing information policy and writing information strategies are a reflection of the network logic of development in the global world.(12)

These days, a country’s capacity to generate the wealth and prosperity necessary for industrialized economies depends heavily on data and information. The Economist captured a potent zeitgeist when it declared in May 2017 that data has surpassed oil as “the world’s most valuable resource”. Since then, international leaders have claimed that data would be the primary driver of economic development in the twenty-first century, including Angela Merkel, Shinzo Abe, and Narendra Modi. Some experts even go beyond, predicting that “data capitalism” would eventually take the place of finance capitalism as the guiding concept of the world economy.(13)

Governments are taking more and more control over and safeguarding its infrastructure and information-related businesses, according to Rozenbad and Mansted. (14) Though not exclusive to authoritarian governments, this is a pattern that is more noticeable there. All governments have a strong economic interest in developing legislative frameworks that will support the expansion of their data-rich economy segments, if nothing else. This is because data plays a crucial role in generating wealth and economic growth. Furthermore, despite the intangibility of data, conventional geopolitical characteristics like population size are closely correlated with the capacity to get and utilize data.

The same writers discuss “the rise of information mercantilism”. A growing number of states also think that the acquisition and application of data is a zero-sum game. The largest commercial success stories of the Information Age are unquestionably monopolists: Facebook, Amazon, Alibaba, Tencent, Alphabet (the parent company of Google), and Amazon. One reason for this is because data access typically creates a positive feedback loop: more data enables businesses to develop more innovative apps and technologies, which boosts their revenue and notoriety and allows them to collect and utilize even more data. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi asserted that “whoever acquires and controls” data will achieve “hegemony”, translating this economic reality into geopolitics.(15)

The problem of the relationship between the informatization of society and the sphere of traditional political relations is in the focus of political science knowledge. However, the dynamism and multi-vector nature of the process of mutual influence of the information and political spheres lead to the emergence of new forms and technologies, which gives rise to serious problems of a theoretical and applied nature.

METHOD

The article is of original research type. Qualitative methodology was applied. Within philosophy of research, the study was based on constructivist paradigm of research, as well as a paradigm of nonlinearity. The main method applied is content-analysis, combined with the elements of grounded theory (initial search for appropriate codes and arranging them in classifications allows us to select literature sources for inclusion).

Structural-functional and institutional analysis was also applied during analysis of the process in Ukrainian media space.

Based on secondary statistical data, main trends characterizing the dynamics of processes in Ukrainian media space are analyzed.

RESULTS

During the years of independence, Ukraine appeared able to organically integrate into the global information space. However, later on, the politicization of the sphere of information policy began to bring its negative results.

Ukrainian scientist Nikolaiets(16) in his research revealed the dependence of the state information policy of Ukraine on the course of events at the front, the success of the implementation of mobilization measures and the nature of the organization of countermeasures to hostile information and psychological operations. It was determined that in the implementation of the state information policy during the years of the full-scale military invasion of the Russian Federation in Ukraine, the signs of internal political struggle and populism with the desire of the authorities to pass off wishful thinking became increasingly more noticeable. It is substantiated that the decrease in trust in the messages broadcast by the 24-hour marathon “The united news #UArazom” is due to the formation of an attitude towards it as a pro-government source of information, as well as doubts about the veracity of some of its content.

It has been proven that centralized communication models in the conditions of accelerated development of the information society gave way to social networks focused on the individualization of content, which contributed to the growth of the impact of influencers. The decrease in trust in official information sources has actualized the spread of alternative sources of content in social networks, video hosting and streaming channels. The government’s betting of the distribution of important information through separate Telegram channels gradually lost its effectiveness. The reason for this can be attributed to the lack of a comprehensive analysis of the situation and the quite frank positioning of some Telegram channels as pro-government.

The strengthening of digital platforms has caused a mass transition of media consumers from broadcast forms of television to the consumption of content from social networks, video hosting, and messengers. The leadership of Telegram channels as a source of information for Ukrainian citizens became clear evidence of this trend.

At the same time, at the beginning of 2024, it was possible to claim that the effectiveness of the state information policy in the conditions of a full-scale invasion of the Russian Federation into Ukraine cannot be assessed unequivocally. The state information policy was quite successful in highlighting the nature of the confrontation between the Russian Federation and Ukraine and in refuting the myth about the Russian army as the “second army of the world”. The refutation of such a myth contributed to a certain expansion of assistance from partner countries to Ukraine in the difficult conditions of the war. During the fall of 2022 – the winter of 2023, the enemy concentrated its efforts on destroying the energy structure of Ukraine. Almost all thermal power plants, a large part of distribution transformer stations and substations were damaged or completely destroyed. Many settlements in Ukraine remained without electricity for a long time. In a number of cities, the lights were turned on for only a few hours a day. The timely dissemination of information about these facts, combined with certain successes on the diplomatic front, made it possible to ensure a rapid increase in the volume of supplies to Ukraine of electric generators, elements of power substations, transformers, etc. from abroad. This made it possible to preserve the efficiency of the domestic energy system and the operation of critical infrastructure elements.

Analyzing the information policy of Ukraine, it should be noted that since the declaration of independence of Ukraine (1991), the ruling circles have not developed a unified approach to its implementation. Each ruling elite pursued a policy in the field of information and communications, based on its own interests. This led to the fact that the Ukrainian state came under information influence from other countries. In addition, the lack of a unified information policy weakened the country’s information security, which resulted in political instability.

However, with the start of the full-scale war of the Russian Federation against Ukraine, the country, being the object of close attention of world geopolitical players, naturally found itself “at the forefront” in the international information discourse. Yet, Ukraine quickly turned from an object of international information policy into its full-fledged subject. However, first in the national information policy, and then in the international information landscape, a certain departure from the principle of transparency began to be observed, which became one of the factors in the “cooling” of ideological, moral, political, and economic support for Ukraine in a number of EU countries. This “cooling” was manifested, in particular, by large-scale protests by Polish carriers and their blocking of border checkpoints with Ukraine. Of course, these protests had a quite sound economic background, but without deterioration of externally directed vectors of Ukrainian information policy, these protests would unlikely be possible.

Skarpa et al.(17) conducted research named “Russo-Ukrainian War and Trust or Mistrust in Information: A Snapshot of Individuals’ Perceptions in Greece”. This study set intended to evaluate how the Greek people felt about the accuracy of the information they had been given on the Russo-Ukrainian War in the spring of 2022. An online questionnaire survey with closed-ended questions on a five-point Likert scale was used to perform the study. In total, 840 answers were received. Most participants thought that the information they had been given regarding the Russo-Ukrainian War was not trustworthy. The authors correctly assert that the Russo-Ukrainian War exhibited many traits of hybrid warfare, including a deluge of false information and conflicting narratives that made it difficult for the general public to independently confirm the facts. Citing Szostek’s(18) paper, it was demonstrated that the most crucial factors for Ukrainian residents to evaluate the veracity of information were firsthand knowledge and information from reliable sources. One of the foundation-scale results of the Skarpa et al.(19) study is that misinformation breeds mistrust of the media and political apathy. As a result, rather than actively supporting the rule, the populace becomes passive.

In general, it should be noted that politicization is a factor inevitably present in information policy - both on the national scale of countries and in the international field.

Tin particular, the only UN specialized organization with a specific mission pertaining to media, communication, and information is the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). In this area, UNESCO’s mandate is directly tied to a normative purpose, utilizing information and communication to promote cross-cultural understanding and international knowledge exchange. However, views on how to accomplish such normative aims diverge greatly in an international community where each member state is guided by unique traditions, values, religious and legal conventions, as well as ideological ideas. Because of this, UNESCO has dealt with contentious and sometimes highly political discussions over the function of communication and information in society as well as the regulation of the increasingly complex informational environment for the good of the international community ever since its founding.

The United States’ proposal to include mass communication in the new organization’s purview during the first conference for UNESCO’s formation in 1945 is where the organization’s mandate in the field of information and communication first emerged.(20) Many of the Western countries attending the conference believed that the globalization of communication and information flows would facilitate the exchange and diffusion of knowledge across national boundaries in the wake of World War II. Consequently, they considered worldwide information sharing as a suitable way to foster understanding among nations, in line with the humanistic values of the recently established international organization.

However, despite their intellectual foundation, the themes of mass communication and information flows quickly became quite political inside UNESCO. The US demand on expanding UNESCO’s scope to include media and information was seen by communist nations such as the Soviet Union as a political propaganda tactic by the West.(20) A number of UNESCO member states have criticized the organization’s “free flow of information” principle in particular, which holds that national boundaries should not impede the transfer of media goods, including news reports and movies, between nations. This principle continues to be a cornerstone of UNESCO’s work. This criticism was not wholly unfounded, as the US had more geopolitical and economic reasons than humanistic ones for expanding UNESCO’s mission to include media and communication.(20) The “free flow of information” notion was one of the US government’s top goals for the post-war era when it became clear that the US would win the war and become the most powerful nation on earth. The US viewed the dominance of the information sector as a crucial component for economic and cultural expansion as well as a means of advancing Western values globally in a world where preexisting orders had been severely disrupted during the war and were still changing as a result of burgeoning decolonization movements.(21) It was also seen as a successful strategy for slowing the global spread of communist ideologies.

One of UNESCO’s primary goals in its early years was to shift the focus of its attention from political discussions to more practical concerns pertaining to information and communication in light of member conflicts. As a result, it began to carry out a number of “Technical Assistance Projects”, which helped to enhance professional training facilities and promoted the growth of national information and communication infrastructures. UNESCO first prioritized aiding war-torn nations in Europe, but eventually turned its attention to emerging nations who had never before benefited from advanced media or even a sophisticated social, political, or economic structure. This move to more practical initiatives made sense for the simple reason that, unlike media and information content, technology was often seen as neutral and value-free, making its transmission seen as an apolitical endeavor. However, detractors quickly surfaced, accusing the Technical Assistance Projects of serving as only another vehicle for economic and cultural hegemony as they let developed nations to export their technological know-how to poor nations, so establishing new sources of dependency.

Policymakers throughout the world are creating national policies to support their information businesses and guard against the information age’s possible drawbacks. Reconciling these disparate national viewpoints is a step in the process of addressing information policies at the international level. The impact of national concerns on the creation of international information regulations is demonstrated by three facets of the transborder data flow debate: economic development, national and cultural sovereignty, and privacy protection.

Various worldwide intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) discuss important policy issues pertaining to the international flow of information. While many IGOs themselves are major producers and disseminators of important information, these arguments are typically highly political and have damaged the agencies’ reputations.

Ideally, the role of journalists in uncovering the truth schematically can be depicted as follows (see figure 1).

Source: Kalogeropoulos et al.(22)

Figure 1. The role of journalists in uncovering the truth

However, in practice, this ideal system (in fact, like any ideal system) rarely exists. An array of multidirectional vectors, including information policy, influence the activities of media.

DISCUSSION

Informal laws, rules, and theological viewpoints pertaining to information, communication, and culture are together referred to as information policy. More specifically, laws, rules, and doctrinal stances pertaining to information generation, processing, flows, access, and usage, as well as other decision-making and practices having constitutive impacts on society, make up information policy.(9)

In terms of Internet freedom, the environment in Ukraine is relatively free, but the Freedom House Internet Freedom Index has noted some setbacks in the last few years. The main reason for concern is the gradual restriction of freedoms due to the ongoing military conflict. Citizens and organizations may be subject to prosecution for expressing views that may be perceived as separatist, and new government policies - whether already implemented or proposed - open up opportunities for the removal, blocking, or filtering of content and legal mass surveillance and censorship of citizens’ electronic communications by law enforcement agencies.

In 2015, the Government called on Ukrainians “to resist Russian propaganda”. Citizens were invited to join the ranks of the “information troops”. The website of the Information Troops of Ukraine was created - i-army.org. The ministry called on ordinary citizens to use social networks “to convey reliable information and combat Russian propaganda”. The move drew criticism abroad. In particular, Gemma Pörzgen, an expert on Eastern Europe from Berlin, considers ‘recruitment’ into the information army “another mistake of an incorrectly organized information policy”. She called the creation of the Ministry of Information Policy itself a mistake.(23) In Ukraine itself, this initiative caused a wave of irony.

At the same time, the Ministry of Information Policy announced the creation of a new news channel, “Ukraine Tomorrow”, aimed at a foreign audience.

In the modern information society, the struggle for space takes place in the information field. The main idea of information wars for space in the postclassical era is to impose a programmable information image of the world on a potential enemy.(24) The new realities of the information society have posed a new, non-traditional task for geopoliticians: to analyze the role of information influences on solving problems at the geopolitical level. It became obvious that namely information influences can change the main geopolitical potential of the state the national mentality, culture, and moral state of people. Thus, the question of the role of the symbolic capital of culture in the information space acquires not an abstract theoretical, but a strategic geopolitical significance.

Analysis of the collision of geopolitical pan-ideas in the information space requires a special dynamic approach as opposed to the usual static political analytics. The new information paradigm of geopolitics means that in the 21st century the fate of spatial relations between states is determined, first of all, by information superiority in virtual space. And in this sense, the development of a geopolitical strategy is the creation of an operational concept based on information superiority and allowing for the growth of a state’s combat power with the help of information technology. (15) Thus, information policy is a strategic tool, and the role and place of a country in international information policy determines its prospects in the geopolitical and geo-economic landscape. Managing information flows is becoming the main lever of power in post-classical geopolitics, which is increasingly taking on virtual forms.(25)

Thus, the question of the role of the symbolic capital of culture in the information space acquires not an abstract theoretical, but a strategic geopolitical significance. Geopolitics is beginning to actively explore the new virtual information space, and the results of this exploration can, without exaggeration, be called revolutionary.

Undoubtedly, as Lukashevska(26) rightly points out, Ukraine’s victory in the war requires not only success on the front, but also in foreign policy, which is highly dependent on the right messages. Mass media is a powerful tool that can reach Western audiences – both politicians and their voters. Lukashevska makes an attempt to answer the question of what a quality Ukraine’ broadcasting for foreign audience should be. In May 2023, the government allocated 3 million 385 thousand hryvnias for the multimedia platform of foreign broadcasting of Ukraine. To counter information threats and disinformation, the Center for Strategic Communications and Information Security (StratCom) was created under the Ministry of Culture. StratCom defines the mission of foreign broadcasting as the representation of the state in the digital and television world abroad, thanks to which the state can implement its foreign policy strategy and popularize itself.(26)

According to the Ukrainian Center for Strategic Communications, “the main goals and tasks of foreign broadcasting are to spread the official position of the country, elaborated narratives and messages, in particular through news, talk shows, and various programs. In any state, broadcasting for foreign audience is one of the most important tools of communication with the international community.”(13)

At the beginning of the full-scale war in Ukraine, they began working on English- and Russian-language platforms for foreign audiences. Currently, the Ukrainian foreign language multimedia platform consists of the TV channels “Dim”, Freedom, social media pages UATV English and UA Arabic, and the English-language website The Gaze.

At the same time, as Lukashevska writes (and this also reflects the official position on Ukraine’s information policy), “what we tell Ukrainians about events in our country and what is broadcast abroad must differ significantly, taking into account the specifics of the region, its knowledge and degree of interest in Ukrainian politics.”(26) But such a discrepancy, although capable of bringing short-term positive results, is critically harmful in the medium- and long term and may well lead to a deterioration of the country’s position in the global information policy.

This is especially important in the context of the so-called “Telegram phenomenon”. Since the beginning of the war, the time spent using the messenger in Ukraine has increased 8 times. Ukrainians actively use Telegram to receive news during the war. Top channels with more than 1 million subscribers are ahead of traditional media. Even with anonymity and dubious quality of news, owners of large networks can earn up to $1 million per month. According to optimistic estimates, the Ukrainian audience of Telegram is 7-10 million users.(27)

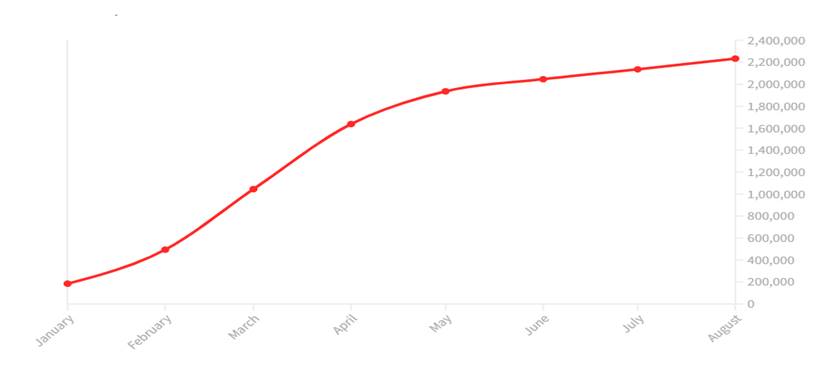

The most popular Telegram channel in the real Ukrainian segment is Trukha Ukraina, which has 2.27 million subscribers. It appeared at the end of autumn 2019. Until the spring of 2022, it specialized in Kharkiv news. Mostly, the channel disseminated criminal news, occasionally - news from the Kharkiv region, and even less often - news about events in Ukraine. By the end of January 2022, Trukha Ukraine gradually increased from several thousand to several tens of thousands of subscribers per month on such content (see figure 2).

Source: Riaboshtan et al. (27)

Figure 2. Growth of Trukha Ukraine audience in 2022

The peak of the channel’s popularity occurred after February 24, 2022, that is, in the beginning of the full-scale invasion of the Russian Federation. Administrators of Trukha Ukraine were ahead of traditional media and official sources thanks to the promptness of publications about the situation in the city, which the Russians are trying to conquer. With the growth of the audience, Trukha Ukraine is trying to satisfy the need for news, the creation and distribution of which is the work of mass media. The channel began to inform less and less about events in Kharkiv, and more and more about national and international events. Administrators of Trukha Ukraine strive to report any news as quickly as possible. Although due to the lack of thorough verification of news, the channel sometimes spreads unreliable information, its most important features are unique efficiency and impartiality, which favorably distinguishes it from official channels. The audience, tired of ideological, slogan-like, embellished, and sometimes psychologically manipulative narratives of official media channels, very positively perceives the Trukha Ukraine channel as a semblance of citizen journalism in its classic version.

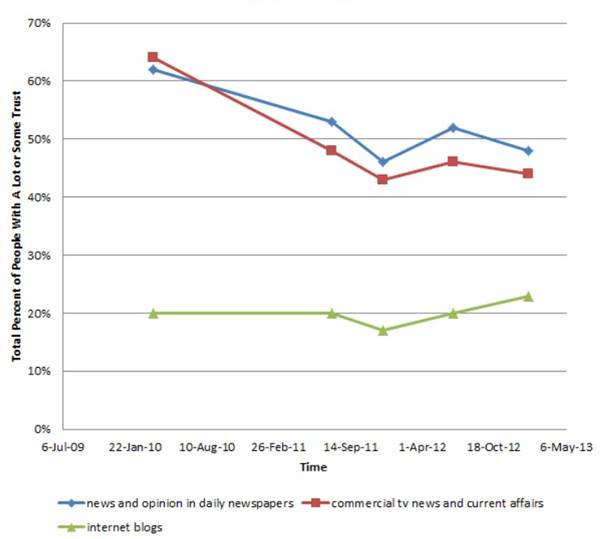

Of course, the information field of Ukrainian civic journalism penetrates and merges into the global information field. The government cannot impose its narratives on foreign audiences thanks to the phenomena of Telegram (YouTube should also be mentioned), citizen journalism, and social media. Moreover, the stark contrast between official “messages” and citizen journalism narratives can seriously tarnish the country’s reputation as a democratic nation abroad.(28,29) The data is clear: during the second decade of the twenty-first century, trust in traditional media (such as newspapers, television news, and current affairs programs) was declining globally, while trust in online news (such as blogs on the internet) was rising. This graph (see figure 3) illustrates this trend. All the more so it this trend is evident today, with ever growing reducing of digital divide and rapid growth of social media activists ‘pool’.

Source: Barclay (7)

Figure 3. Dynamics of trust in media in the period of 2009-2013

Thus, the urgent task of Ukrainian information policy should be the search for reasonable compromise between the need to ensure information security of the country and resists Russian information warfare threats from the one side, and the necessity to retain democratic image of Ukraine in global information space from the other side, thus strengthening its strategic perspectives in international relations and sustainable peacebuilding.

CONCLUSION

In Ukraine, the question of the integrity of the system of regulation of the information sphere and the construction of information policy, in particular, the development of the national information space and official communication at the state level, which is connected with both objective and subjective factors, remains open. On the one hand, it is worth pointing out the rapid pace of development of information technologies and information dissemination platforms, and on the other hand, the public sensitivity of issues of state regulation of mass media and communication.(30)

One should not forget that the process of informatization of politics is ambivalent and bilateral in nature. The needs of actors in the struggle for power and hegemony on a national, regional, and global scale force them to use the achievements of the information revolution for their own utilitarian purposes. In the scientific community, this circumstance was reflected in the emergence of such definitions as cyberpolitics, noopolitics, media politics.

In the post-bipolar world, the possibilities for intense influence on worldviews have increased by an order of magnitude, which occurs not only through distortion of information flows, but also through more camouflaged operations that have a political, ideological, and moral impact on the individual and collective political consciousness of individuals and social communities.

The presence of effective electronic communications and transnational social networks, which are almost impossible to bring under the control of a national state, creates serious competition for the classical systems of education and upbringing, and the ideological principles disseminated through them often come into conflict with the achievements of world culture and the norms of traditional morality. Namely in this segment of the information sphere, elements of informatization and politics intertwine and overlap each other, giving rise to hybrid forms of both areas of life.

Thus, the phenomenon of informatization of politics not only determines the level of protection of national interests in the information sphere, but also increases the requirements for the state of the entire range of problems in the political, economic, social, military, environmental fields, depending on their level of involvement in the global information space.

As a result of the aggression of the Russian Federation, Ukraine is faced with very difficult challenges in the field of information policy, and the problem of choosing the optimal vector for designing and developing an information policy for participation in the global information space is of strategic importance. At the same time, the multidirectionality of influencing forces and the potential of citizen journalism and social media determine the need for systemic and matrix approaches in this area, not only with modeling short-term effects, but also with long-term forecasting.

REFERENCES

1. Drezner DW. Technological change and international relations. International Relations 2019; 33(2):286-303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117819834629.

2. Guiora A. Cybersecurity: Geopolitics, law, and policy. Routledge; 2017.

3. Schiller D, Zhao Y, Ciafone A. The geopolitics of information. University of Illinois Press; 2024.

4. Klinger L, Kreiss D, Mutsvairo B. Platforms, power, and politics: An introduction to political communication in the digital age. Polity; 2023.

5. Risse M. Political theory of the digital age. Cambridge University Press; 2023.

6. Kolodko G. Global consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: The economics and politics of the second Cold War. Springer; 2023.

7. Barclay D. Fake news, propaganda, and plain old lies: How to find trustworthy Information in the Digital Age. Lanham Rowman & Littlefield; 2018.

8. Barclay D. Fake news, propaganda, and plain old lies: How to find trustworthy Information in the Digital Age. Lanham Rowman & Littlefield; 2018.

9. Braman S. Defining information policy. Journal of Information Policy 2011; 1:1-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.5325/jinfopoli.1.2011.1

10. Cox M. Ukraine: Russia’s war and the future of the global order. LSE Press; 2023.

11. Baum MA, Potter PB. Media, public opinion, and foreign policy in the age of social media. The Journal of Politics 2019;81(2): 747-756. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/702233

12. Horulko V. The role and place of information security in the general system of national security of the state. Bulletin of Kharkiv National University named after V. N. Karazin. Series “Law” 2022; 34:103-108. https://doi.org/10.26565/2075-1834-2022-34-12

13. Wasserman H. Media, geopolitics, and power: A view from the Global South (Geopolitics of Information). University of Illinois Press; 2018.

14. Rozenbad E, Mansted K. The geopolitics of information. Belfer Center of Harvard Kennedy School, Paper, May; 2019. https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/2019-08/GeopoliticsInformation.pdf

15. Gu H. Data, Big Tech, and the new concept of sovereignty. Journal of Chinese Political Science 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-023-09855-1

16. Nikolaiets Yu. State information policy of Ukraine in the conditions of a full-scale military invasion of Russian Federation: Social mobilization potential and efficiency. Political Studies 2024;1(7):42-67. (in Ukrainian). https://doi.org/10.53317/2786-4774-2024-1-3

17. Skarpa PE, Simoglou KB, Garoufallou E. Russo-Ukrainian War and trust or mistrust in information: A snapshot of individuals’ perceptions in Greece. Journalism and Media 2021;4: 835-852. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030052

18. Szostek J. Nothing is true? The credibility of news and conflicting narratives during “Information War” in Ukraine. The International Journal of Press/Politics 2018;23(1);116-135. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217743258Benjamin M, Davies N. War in Ukraine: Making sense of a senseless conflict. OR Books; 2022.

19. Skarpa PE, Simoglou KB, Garoufallou E. Russo-Ukrainian War and trust or mistrust in information: A snapshot of individuals’ perceptions in Greece. Journalism and Media 2021;4: 835-852. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030052

20. Pohle J. International information policy: UNESCO in historical perspective, In: Duff, Alistair S. (Ed.): Research Handbook on Information Policy (pp. 96-112). Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham; 2021. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781789903584.00017

21. Fridman O, Kabernik V, Pearce JC (Eds.). Hybrid conflicts and information warfare: new labels, old politics. Lynne Rienner Publishers, Incorporated; 2019.

22. Kalogeropoulos A, Rori L, & Dimitrakopoulou D. ‘Social media help me distinguish between truth and lies’: News consumption in the polarised and low-trust media landscape of Greece. South European Society and Politics 2021;26(1):109-132. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2021.1980941

23. Benjamin M, Davies N. War in Ukraine: Making sense of a senseless conflict. OR Books; 2022.

24. Mueller M. Networks and states: The global politics of Internet governance. MIT Press; 2013.

25. Slaughter M, McCormick D. Data is power. Foreign Affairs’ 2021, April 16. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-04-16/data-power-new-rules-digital-age

26. Lukashevska A. The voice of Ukraine in the world: what should be the quality of foreign language of Ukraine. 24Channel; 2023, December 15. Available at: https://24tv.ua/inomovlennya-ukrayini-yak-donositi-do-zahidnoyi-auditoriyi-pravdu_n2452951

27. Riaboshtan I, Pivtorak O, Ilyuk K. From Trukha to Gordon: the most popular channels of the Ukrainian Telegram segment. Detector Media 2022, September 9. https://detector.media/monitorynh-internetu/article/202665/2022-09-09-vid-trukhy-do-gordona-naypopulyarnishi-kanaly-ukrainskogo-segmenta-telegram/

28. Namdarian L, Rasuli B. National information policy: Framework, dimensions, and components. Journal of Studies in Library and Information Science 2022;14(1):63-91.

29. Saaida M, Alhouseini M. The influence of social media on contemporary global politics. International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews 2023;10(1):799-809. https://dspace.pass.ps/handle/123456789/311

30. Togtarbay B, Zhaksylyk A, Mukasheva MT, Turzhan O, Omashev NO. The role of citizen journalism in society: An analysis based on foreign theory and Kazakhstani experience. Newspaper Research Journal 2024; 45(1): 25-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/07395329231213036

FINANCING

The authors did not receive financing for the development of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Andrii Liubchenko, Volodymyr Коzakov, Svitlana Petkun, Roza Vinetska.

Data curation: Andrii Liubchenko, Svitlana Petkun, Oleksandr Ignatenko, Roza Vinetska.

Formal analysis: Andrii Liubchenko, Oleksandr Ignatenko, Roza Vinetska.

Research: Andrii Liubchenko, Volodymyr Коzakov, Svitlana Petkun.

Methodology: Andrii Liubchenko, Volodymyr Коzakov, Oleksandr Ignatenko, Roza Vinetska

Project management: Andrii Liubchenko, Volodymyr Коzakov, Svitlana Petkun, Oleksandr Ignatenko.

Software: Andrii Liubchenko, Volodymyr Коzakov, Svitlana Petkun, Roza Vinetska.

Supervision: Andrii Liubchenko, Volodymyr Коzakov, Svitlana Petkun, Oleksandr Ignatenko, Roza Vinetska.

Validation: Volodymyr Коzakov, Svitlana Petkun, Oleksandr Ignatenko, Roza Vinetska.

Writing - original draft: Andrii Liubchenko, Volodymyr Коzakov, Svitlana Petkun, Oleksandr Ignatenko.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Andrii Liubchenko, Volodymyr Коzakov, Svitlana Petkun, Oleksandr Ignatenko, Roza Vinetska.