doi: 10.56294/sctconf2024.1244

ORIGINAL

Subtitling profanity into Malay: Balancing formal and creative taboo expressions

Subtitulación de blasfemias al malayo: equilibrio entre expresiones tabú formales y creativas

1Universiti Utara Malaysia, School of Languages, Civilisation and Philosophy. Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia.

Cite as: Mohamad Zakuan TI. Subtitling profanity into Malay: Balancing formal and creative taboo expressions. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2024; 3:.1244. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2024.1244

Submitted: 30-03-2024 Revised: 10-07-2024 Accepted: 16-10-2024 Published: 17-10-2024

Editor: Dr.

William Castillo-González ![]()

ABSTRACT

Introduction: translation of swearwords has unceasingly gained traction in audiovisual translation. In subtitling, swearing does not only warrant linguistic consideration but other multimodal elements, such as intonation and body movement. Apart from subtitling technicalities, the difficulties of swearword translation are also impeded by their explicit and implicit forms, as well as the linguistic-cultural differences in source-target texts. This study aims to deliberate on the Malay translation of English swearwords of ‘fuck’ and ‘shit’ in two episodes of Netflix TV series The History of Swearwords.

Method: to this end, it employs a comparative and descriptive analysis by developing a parallel corpus by utilising AntConc and AntPConc software. The selection of Netflix posits no local law or policy restrictions and censorship.

Results: the comparative analysis found a linkup between creative and formal subtitling of the swearwords, which signals a prevalent pragmatic and cultural foundation in the translation, especially vis-à-vis the deletion and neutralisation procedures. The study also raises other notable concerns, such as the identification and semantic comprehension of swearwords by the series subtitlers.

Conclusions: overall, the study posits that the socio-pragmatic factors, among others are still central for the English-Malay translation strategies of the swearwords in maintaining both linguistic accuracy and cultural appropriateness for target audience.

Keywords: Swearword; Profanity; Taboo; Subtitling; Netflix.

RESUMEN

Introducción: la traducción de palabrotas no ha dejado de ganar terreno en la traducción audiovisual. En la subtitulación, las palabrotas no sólo merecen consideración lingüística, sino también otros elementos multimodales, como la entonación y el movimiento corporal. Aparte de los aspectos técnicos de la subtitulación, las dificultades de la traducción de palabrotas también se ven obstaculizadas por sus formas explícitas e implícitas, así como por las diferencias lingüístico-culturales de los textos de origen y destino. Este estudio pretende deliberar sobre la traducción al malayo de las palabrotas inglesas «fuck» y «shit» en dos episodios de la serie de televisión de Netflix The History of Swearwords.

Método: para ello, emplea un análisis comparativo y descriptivo mediante la elaboración de un corpus paralelo utilizando los programas informáticos AntConc y AntPConc. La selección de Netflix presupone la ausencia de restricciones legales o políticas locales y de censura.

Resultados: el análisis comparativo encontró un vínculo entre la subtitulación creativa y la subtitulación formal de las palabrotas, lo que indica una base pragmática y cultural predominante en la traducción, especialmente en lo que respecta a los procedimientos de supresión y neutralización. El estudio también plantea otras cuestiones importantes, como la identificación y comprensión semántica de las palabrotas por parte de los subtituladores de las series.

Conclusiones: en general, el estudio postula que los factores sociopragmáticos, entre otros, siguen siendo fundamentales para las estrategias de traducción inglés-malayo de las palabrotas a la hora de mantener tanto la precisión lingüística como la adecuación cultural al público destinatario.

Palabras clave: Palabrotas; Profanidad; Tabú; Subtitulación; Netflix.

INTRODUCTION

The Industrial Revolutions 4.0 and 5.0 mark a worldwide technological progress. The omnipresent information generation and retrieval tools, machine learning and automation, and (multi)media communication, among other achievements, are now central to the global audience. A global community not only presently enjoys unlimited access to local audiovisual (AV) products, but also global ones. Likewise, the globally marketed and distributed AV products are also inclusive to a mass audience with an array of language and translation options. This, inter alia, results in the clash of pop culture, language and tradition. Vance(1), in this regard, deems that both linguistic and cultural melting pots are a feature of a multilingual society which celebrates diversity and interconnectedness, among other variables.

One of the prevailing linguistic issues is swearwords. Although many deem swearing and profanity taboo and inappropriate to be screened for all audiences, especially children, the audience reception of AV products varies extensively. Besides emotional expression, swearing may also convey humour, social bonding and non-conformity to authority.(2) In some communities, swearing is regarded as very offensive and sensitive, whilst others may perceive it as a part of their conversational tradition. This also includes other negatively connotated cases, such as the sexually decorated theme parks in South Korea(3) and Denmark.(4) Film-wise, such examples may constitute content or/and audio banning or censoring from regulatory bodies and distributors, as seen in the banning of Deadpool in China(5) and The Shawshank Redemption in Malaysia.(6)

With regard to AV translation, the intricacies of the structure and reception of swearwords certainly hamper the decision-making in determining accommodating equivalence for the target audience. Certain AV modes are also of respective technical constraints, such as the spatial and temporal features of subtitling and dubbing, such as spotting (cueing/time coding), duration of subtitle display and formatting.(7) By grounding in this premise, the study attempts to analyse the Malay translation of two swearwords as screened by the video streaming platform Netflix. Two episodes of the Netflix television series, The History of Swearwords(8) were selected as the corpus. A comparative analysis was performed to descriptively compare the English-Malay translations of swearwords to determine their translation strategies and the underlying thematic issues, if any.

Swearing and taboo language

At base, swearing is predominantly perceived and featured in taboo language. The lexis of taboo has its roots in a range of themes. Allan and Burridge(9), for example, record five taboo-related foci, namely (i) bodies and their effluvia (sweat, snot, faeces, menstrual fluid, etc.); (ii) organs and sexual acts, micturition, and defecation; (iii) diseases, death and killing (including hunting and fishing); (iv) naming, addressing, touching, and viewing persons and sacred beings; and (v) objects and places; food gathering, preparation as well as consumption. Taboo is also framed as a social constraint on individual behaviour that may cause discomfort, danger or injury. While it can encompass both explicit and implicit, bad language can in general feature domain-specific jargon, slang, swearing and cussing, and insults (p. 88-9).

Taboo language is also perceived to be well-embedded in the English language and culture. Taylor(in 10) wittily asserts that if English was the native language of an indigenous tribe, the anthropologists would have proposed to include taboo language as one of the main traits of the language. On a parallel note, Allan and Burridge(9,11) frame taboo language under the means of orthophemism, euphemism, and dysphemism. The three terms respectively denote formal (neutral), polite (softened) and impolite (offensive) expressions. A clear example is the rendition of ‘die’ (orthophemism) into ‘pass away’ (euphemism) and ‘kick the bucket’ (dysphemism). Certainly, in relevant settings, they may be utilised to meet specific contextual objectives, and in turn, audience responses.

Swearing is predominantly regarded as offensive and dysphemistic. According to Parini(11), it is most commonly communicated verbally (diamesic dimension) and expletively. As opposed to the orthophemistic and euphemistic expressions, impolite references are oftentimes emotively driven and may evoke speaker and audience reactions. English swearwords can also be homonymous (have multiple meanings) and have humorous connotations. For instance, the “This shit’s gonna have nuts in it” dialogue by Deadpool(12) carries both literal (defecation reference) and pragmatic (drawn revenge plan on the whiteboard) meanings.

Screening of taboo films and enforcement of laws

Based on the above-mentioned explanation, the audience’s acceptance towards taboo references may be markedly subjective and relative - some may accept them, while others reject and view them negatively and sensitively. Although there is a perception that the level of acceptance in Western society is more open compared to Asian countries, historical evidence shows that the use of taboo and vulgar words also initially had negative implications in the West. For instance, the use of ‘fuck’ and ‘cunt’ in print may result in court prosecution and imprisonment.(13)

The displayed taboo elements are also omitted and filtered on-screen using various methods, including a range of specific strategies for select audiovisual translation modes. A clear example can be seen in the negative reception of religious-themed taboo humour references to Father Ted sitcom in Italy. Due to the viewers’ ill-perception of the TV series, the original soundtrack is completely dubbed in the target text.(14) A change of AVT mode also presupposes a removal of certain taboo elements from the source text. For example, according to Parini(11), the number of taboo words in the Pulp Fiction film significantly changed (from 389 to 272) after being dubbed in Italian.

In addition to the AVT mode selection, the implementation of translation strategies is also constrained by legal restrictions. In Malaysia, for example, the enforcement of the Film Censors Act 2002 Provision (Act 620) and Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission Act (1998) (Act 588) exemplifies several guidelines of content regulation for film, television and online screening.(15,16) The list, among others, includes the 2024 Film Censorship Guidelines, CMCF Content Code, and Film Censorship Circulars. The latest film censorship guideline, for instance, gives a special remark on AVT by necessitating the production of non-Malay film subtitles for censorship purposes.(17) Generally, the content production against the two acts is not allowed to be broadcasted and will undergo a screening process (audio and/or visual), if necessary.

Although the broadcasting rights of audiovisual content in Malaysia are generally subject to local laws and regulations, the same may not apply if the broadcaster is not registered in this country. Video streaming platform broadcasters, such as Netflix, for example, have faced criticism from various parties due to the unfiltered nature of their content that is deemed against local values.(18) Ahmad Idham(19), the former National Film Development Corporation Malaysia (FINAS) CEO, here asserts that unregulated content distribution and screening may affect children’s cognitive development in the future. His argument, however, also received a mixed reaction from the local community, as voiced by actress Sharifah Amani(20), among others.

Following this controversy, former Minister of Communications and Multimedia, Annuar Musa(21) notes that the Malaysian government has no censorship authority over the streaming platform services, as Netflix is not locally registered and licensed. He further suggested that the ministry engage in discussions with the relevant companies outside the country to explain Malaysia’s stance on this matter.

A literature search indicates a research focus on translation studies of taboo-oriented references and swearwords and comparative analysis (between source and target texts) covering various AVT modes. For example, Ávila-Cabrera’s(22) study on the taboo translation of three English films into Spanish (Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, and Inglourious Basterds) exemplifies various translation strategies. Subtitling for Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction often employs strategies of omission, literal translation, reformulation, and replacement, whereas the third film prioritises literal translation. For reference, the analysis of taboo word categorisation shows that the films Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction are dominated by the use of abusive swearing with a derogatory tone (abusive swearing - derogatory); whereas Inglourious Basterds is filled with taboo terms related to murder and death.

Wu(23), on the other hand, prioritises the translation of select key taboo-related terms, such as fuck and shit - the two most frequently used swearwords in English.(10) The translation patterns of these two lexes are examined using a comparable corpus (English to Chinese) in the context of the TV series Big Little Lies, revealing the use of four translation strategies, namely pragmatic equivalence, softening, de-swearing, and omission. The use of corpora is also employed in the study by Abu-Rayyash et al.(24) which scrutinises the subtitling of 1564 swearwords into Arabic in 40 Netflix films and TV series. This study, among other things, found that the lexes of fuck, shit, damn, ass, bitch, bastard, asshole, dick, cunt, and pussy are most commonly used, and concluded the use of filtering, quality reduction, and censorship strategies for translating certain swearwords as are most frequently applied over other strategies.

One salient feature of the English-Arabic taboo translation studies(24,25,26) is the presupposition of the authority intervention in decision-making translation processes due to religious, political and social concerns. As put by Abdelaal, the linguistic differences between standard Arabic (modern) and their nation-based variants (Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, etc.) also play a role in determining the choice of words and translation strategies that prioritise euphemisms. Here, Modern Arabic serves as a unifying medium for all Arab countries; hence its high value is preserved, deemed polite and used by the educated class. Therefore, the use of less prestigious and substandard language, such as taboo elements and vulgarities, is not maintained in written form, including idioms.

A similar description is also raised in the context of Malaysia. The analysis of taboo humour translation by Mohamad Zakuan and Hasuria(15), for example, cites the external factors such as censorship and enforcement of acts, practices and formats of satire, and the translator’s mistakes as the determining factors of taboo humour strategies in Malaysia, besides the internal factors of language, culture, forms and methods of delivering taboo humour. Subtitling the Malay taboo language into English is also of recent concern.(27) By framing the analysis into four translation strategies of taboo-to-taboo; taboo-to-non-taboo; euphemising/softening; and omission, Mohamad Zakuan and Khairul Faiz also make further notes on the thematic intricacies of local and multilingual taboo references.

METHOD

This study is qualitative and descriptive. For this purpose, the first two episodes of the Netflix TV series The History of Swearwords were selected as the study corpus. This TV series is themed around humour and hosted in a casual documentary format by Hollywood actor, Nicholas Cage. For the record, a total of eight episodes have been produced, and each episode is given a different swearword-themed title. In general terms, each episode covers the historical aspect (word formation) of the designated vocabulary, its use and contexts from academics, actors, and comedians from casual interviews. For Malaysian viewers, Netflix labels all episodes in this TV series 18+ (language), denoting suitable for audiences aged 18 and above due to its explicit language.

The first episode of this TV series is titled “F**k”, while the second episode is titled “Sh*t”. The selection of both as the corpus is based on several justifications. First, both of these lexes are considered the most frequently used swearwords in the context of English swearing. Relating to this, Wajnryb(10) states that every time he encounters a new dictionary, he will look for the word fuck and use it as a litmus test to determine the quality of the dictionary. For instance, states that every time he encounters a new dictionary, he will look for the word fuck and use it as a litmus test to determine the quality of the dictionary. Secondly, this TV series is broadcast through the international video streaming platform, Netflix. His choice is supported by the fact that his curse words were not filtered. As opposed to local streaming platforms warranting local policy compliance (refer to the above-said discussions on Act 620 and Act 588), the audience watching this TV series is not restricted by the filtered/censored profanity dialogue; hence taboo references may be subtitled directly (dysphemism) for audience viewership.

This study applies a comparative analysis of subtitled taboo terms by building an English-Malay parallel corpus for both episodes of this TV series. By utilising the AntConc and AntPConc corpus analysis tools, all forms and variations of the word fuck and shit are examined based on the contexts of the source text and their translation. Subsequent findings are then categorised based on relevant lexical structure to determine the salient and dominant patterns of subtitling strategies for specific key terms. Based on Allan and Burridge(9), the analysis also determines the rate of X-phemism in the translation if the taboo elements are rendered in the target language.

RESULTS

Tables 1 and 2 below show the structural variations for the lexemes of ‘fuck’ and ‘shit’ in the source text:

|

Table 1. Variations of the word ‘fuck’ |

||||||

|

No. |

Cluster |

Rank |

Freq |

Range |

NormFreq |

NormRange |

|

|

fuck |

1 |

111 |

2 |

0,712 |

1 |

|

|

fuckin |

2 |

10 |

1 |

0,064 |

0,5 |

|

|

fucking |

3 |

7 |

2 |

0,045 |

1 |

|

|

fucked |

4 |

5 |

2 |

0,032 |

1 |

|

|

motherfucker |

4 |

5 |

2 |

0,032 |

1 |

|

|

motherfuckin |

4 |

5 |

1 |

0,032 |

0,5 |

|

|

fucker |

7 |

2 |

1 |

0,013 |

0,5 |

|

|

lefucker |

7 |

2 |

1 |

0,013 |

0,5 |

|

|

fuckboy |

9 |

1 |

1 |

0,006 |

0,5 |

|

|

fuckbutter |

9 |

1 |

1 |

0,006 |

0,5 |

|

|

fuckebythenavele |

9 |

1 |

1 |

0,006 |

0,5 |

|

|

fuckers |

9 |

1 |

1 |

0,006 |

0,5 |

|

|

fuckhead |

9 |

1 |

1 |

0,006 |

0,5 |

|

|

fuckwad |

9 |

1 |

1 |

0,006 |

0,5 |

|

|

fuckwit |

9 |

1 |

1 |

0,006 |

0,5 |

|

|

motherfuck |

9 |

1 |

1 |

0,006 |

0,5 |

|

|

motherfucking |

9 |

1 |

1 |

0,006 |

0,5 |

|

Source: AntConc output |

||||||

|

Table 2. Variations in the word structure of ‘shit’ |

||||||

|

No. |

Cluster |

Rank |

Freq |

Range |

NormFreq |

NormRange |

|

|

shit |

1 |

111 |

2 |

0,91 |

1 |

|

|

bullshit |

2 |

3 |

1 |

0,025 |

0,5 |

|

|

chickenshit |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0,008 |

0,5 |

|

|

horseshit |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0,008 |

0,5 |

|

|

shitfaced |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0,008 |

0,5 |

|

|

shithead |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0,008 |

0,5 |

|

|

shitload |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0,008 |

0,5 |

|

|

shits |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0,008 |

0,5 |

|

|

shitting |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0,008 |

0,5 |

|

|

shitty |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0,008 |

0,5 |

|

Source: AntConc output |

||||||

Overall, both lexes exhibit significant morpheme structure variations, with seventeen forms for the word ‘fuck’, and ten for ‘shit’. However, it can be observed that the frequency of both forms of the swearwords in the corpus is predominantly in their base forms, which is one hundred eleven (111). Compared to ‘shit’, the lexis of ‘fuck’ also has several variations that are only distinguished by their pronunciation and plural form, and do not include standard spelling, such as the variations of fucking–fuckin, motherfucking–motherfuckin’, and fucker–fuckers. Whilst the words fuck and shit can essentially be used as verbs and nouns, their structural variations also involve the addition and/or combination of other morphemes within the same word class depending on their position in respective dialogues, besides the addition of suffixes -(in)g or -y to form adjectives. It is also important to note that the two tables also display, among others, several examples of neologisms by combining swearwords with other words in the source language, such as fuck+boy and shit+head.

Lexis of ‘fuck’

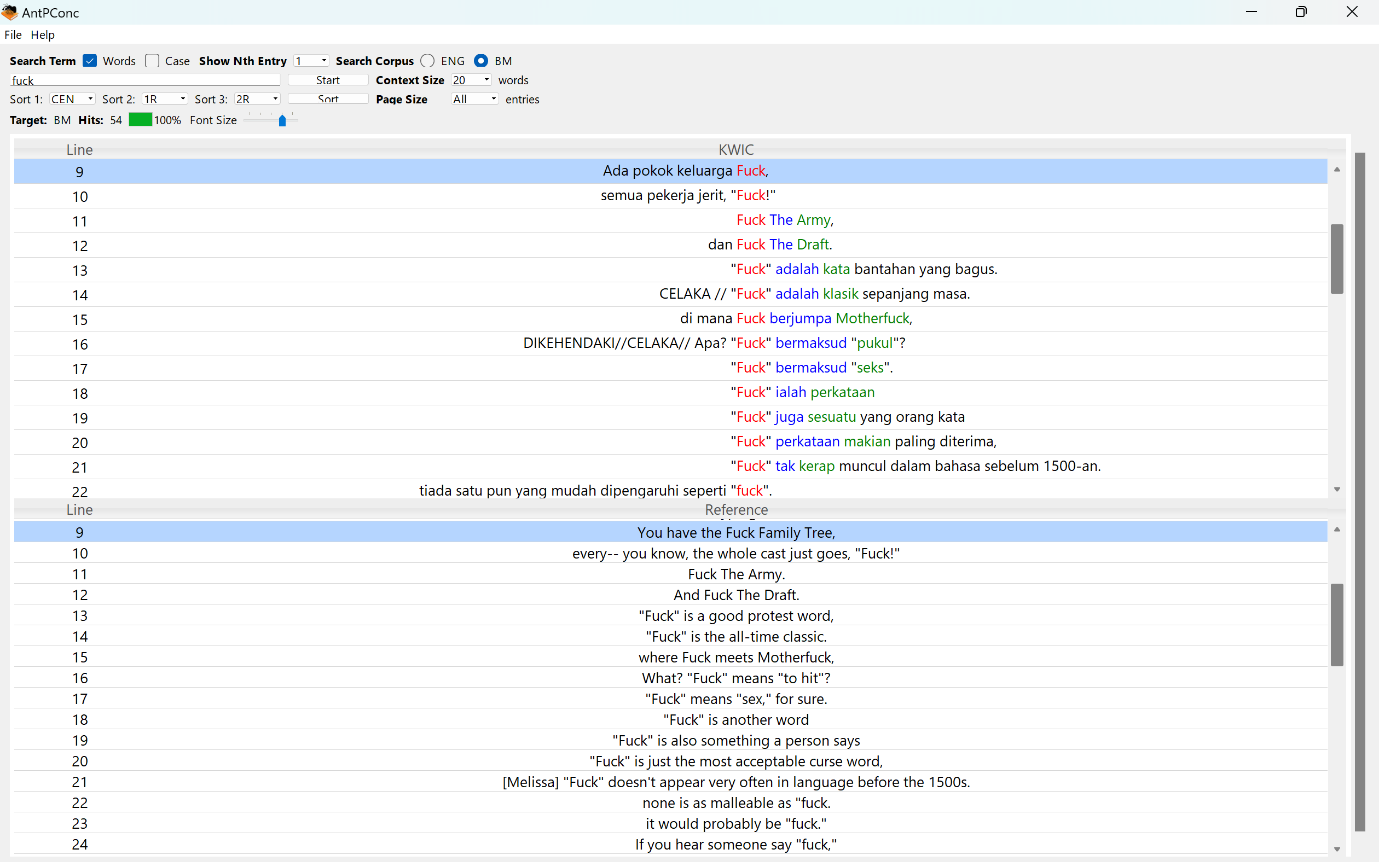

The comparative analysis of the source text and translation also demonstrates the implementation of intricate paraphrasing strategies. At large, examples of ‘fuck’ in both episodes of this TV series are rendered in the target text using four main strategies: (direct) borrowing, pragmatic equivalence, softening, and deletion. The first strategy refers to the retention of the English word “fuck” in the Malay subtitles. As the TV series is documentary in nature, its retention mainly serves its referential use, i.e. to explicate the meaning, history and (contextual) use of the word in relevant settings. ‘Fuck’ is also used as a proper noun, as exemplified in various examples, such as the Fuck family/surname, (John) Lefucker, and (Uncle) Fucker. The following diagram (figure 1) illustrates the context of borrowing:

Figure 1. Borrowing strategy for ‘fuck’

Source: AntPConc output

The second strategy is pragmatic equivalence. According to Díaz-Pérez(28), this strategy refers to the functional equivalence of two aspects, namely pragmatic function and intonation. In the Malay language, the use of this strategy is most commonly subtitled using orthophemism (formal expression) by utilising the term “celaka”, besides the more explicit term of “pergi jahanam”. The context of the first term includes the phrasal verb “fuck you” (celaka); referential example “You can use “fuck” in absolutely any way” (Awak boleh guna “celaka” dalam semua cara); and exclamation “fuuuuuck!” (celaka). The phrase “pergi jahanam”, on the other hand, is only applied when subtitling the “fuck the police” phrase (pergi jahanam polis). Besides these two terms, another example of pragmatic equivalence is also illustrated using the term “bedebah”, as in the example “you little fucker” (budak bedebah celaka).

Softening strategies are also found in the analysis. In essence, this strategy refers to the use of mitigated and less explicit terms as opposed to the more direct source text references (euphemisms). The most common is the use of the term “tak guna”, which is not explicit in nature. In three different scenes, the host (Nicolas Cage) repeatedly uttered the word “fuck” five times, but the subtitles only displayed “tak guna” once. Another example of this strategy is the translation of “fuck” (pengecut or coward), “fuckhead” (bangang or fat-headed), and “fuckwad” (bodoh or stupid). Similar to the previous example, all three are not naturally explicit, although they carry negative loads semantically).

The last strategy is deletion. Unlike the previous three strategies, deletion completely removes taboo references in the subtitles, which in turn displays free-from-profanity translations. Nicolas Cage, for example, sings the expletive word “fuck” three times in three different scenes in the source text, yet they are not screened in the subtitles. Multiple examples of deletion are also observed in the translation of the word “fuckin” or “fucking” as emphasis, as in the examples of “everything’s fuckin’ funnier” (semuanya lebih lucu), “have a great fuckin’ night” (selamat malam), “are you fucking kidding me?” (awak berguraukah?), and “those annoying spoilsports” (orang-orang); and also noun reference, such as “you, the troublemaker, should be on brain detail” (awaklah orang yang patut tahu).

Lexis of ‘shit’

Lexis of ‘shit’, on the other hand, is rendered in the target language through five main strategies, namely (direct) borrowing, pragmatic equivalence, direct omission, softening, and neutralisation (de-swearing). Following the first translation strategy of fuck, many examples of ‘shit’ is also maintained in the translation to retain its referential status. The examples include “shit comes from...” (“shit” berasal dari...) and “shit is also very effective” (“shit” juga sangat berkesan). Compared to the creative wordplay of fuck as human names in the TV series, this form of swearing, however, is only formed by the combination of other words (neologisms), such as “shitload “, “chickenshit”, and “horseshit”, as displayed in table 2.

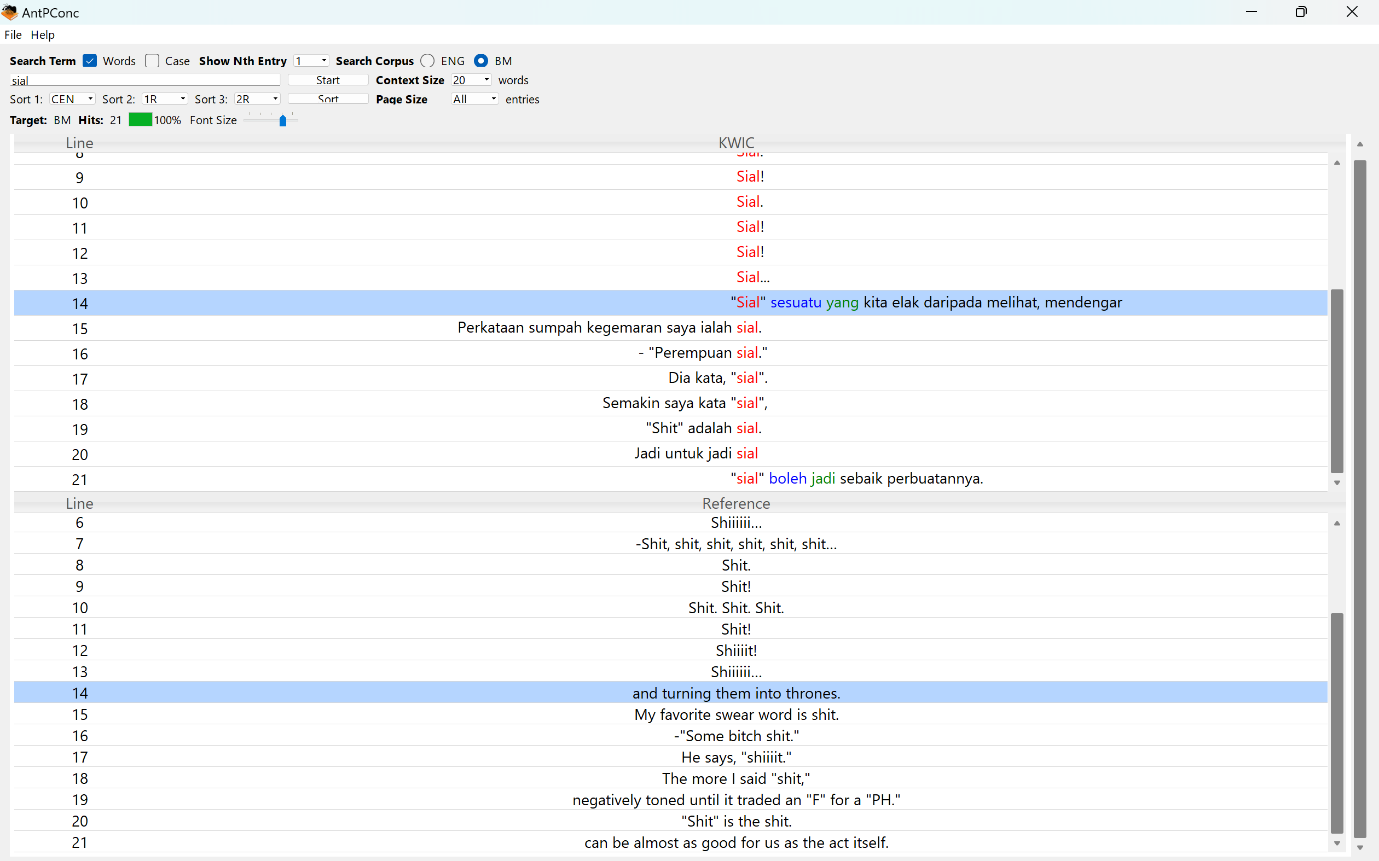

The next is pragmatic equivalence. In general, ‘shit’ is paralleled to “sial” in the translation, which carries a similar function and intonation to the original text. The use of this dysphemistic equivalence is often used by the subtitlers, including when translating exclamatory remarks. For instance, at the beginning of the second episode, actor Isaiah Whitlock begins his attempt to record the longest utterance of “shit”, which is subsequently delivered across multiple scenes until the end of the episode. Here, although certain scene frames only display the utterance of “shiii...” and “...iiii...” separately, the dialogue still presents the profanity in its full form, which is “sial...”. Akin to the previous example of ‘fuck’, multiple expressions of ‘shit’ in a scene are also displayed using the one-word “sial” in the Malay language. The diagram below (figure 2) illustrates several contexts of the translation of ‘sial’.

Figure 2. Pragmatic equivalence strategy of ‘sial’

Source: AntPConc output

The third strategy is deletion. Parallel to the deletion strategy of ‘fuck’, a number of ‘shit’ references are also omitted in the subtitles, albeit with an exclamatory tone. The examples are “shit!”, “damn shit!”, “shingle shit!”, and “is this the shit that I ordered?” (inikah yang saya pesan?) and “Once again, we owed a shitload of thanks” (Sekali lagi, kita terhutang budi), which are entirely free from the source text taboo references.

The fourth (softening, or quality reduction) and fifth (neutralisation) strategies are essentially of similar characteristics, but their usage is contextually dissimilar. Following the previous example of “fuck”, some instances of “shit” are also rendered in the target language as “tak guna”, which reflects the low explicitation quality of the profane reference. The application of this strategy is seen in an array of scenes, such as “Shit. Shit! Shit.” (Tak guna.); “Shit on a goddamn shingle!” (Tak guna!); and “-Goddamn shit!” (Tak guna!); even though some are accompanied by exclamation marks for intonation emphasis. Similar translation equivalence is also found for neologism, such as the “it is total horseshit” dialogue (ia memang mengarut). Neutralisation, on the other hand, refers to the process of removing swearwords and replacing them with functional equivalents without the taboo references, such as the use of the word “alamak!” (literally ‘oh no!’) for “Shit!” and “Holy shit!” references; and “benda” (literally ‘item’) in the example of “the shit that I ordered” (benda yang saya pesan).

DISCUSSION

The comparative analysis found several key takeaways. First, the retention and translation of both expletive lexes of ‘fuck’ and ‘shit’ in the subtitles essentially correspond to Netflix’s no-censorship policy, which leaves the subtitlers free to employ creativity when translating. As the corpus analysis suggests, the range of different subtitling strategies of taboo references also justifies this observation. As a comparison, a study by Mohamad Zakuan and Hasuria(15) identifies several censorship issues in the Deadpool film, especially the reception and comprehension discrepancy of the target audience who did not hear (censored) profanity references in the source text but could read them in the Malay subtitles. The same study also found technical filtering errors, such as the explicit taboo humour references, like “dick-tips” and “cock-gobbler”, which were not filtered.

Whilst the findings indicate the presence of the subtitlers’ creative side, the study also found that the word selection (diction) for translating the two swearwords is still fixed to certain vocabularies and limited. Generally, apart from the retention strategy (borrowing), the lexis of fuck is mostly formally rendered in Malay as “celaka”, while shit is rendered as “sial”. The discovery can certainly be deemed contradictory against the array of contextually suitable choices in the Dewan Bahasa (English-Malay) dictionary. For reference, the equivalent translation of the expletive ‘fuck’ is “puki mak”, aside from three mitigated equivalents of “babi”, “celaka”, and “sial”.(29) The dictionary also lists three equivalents for ‘shit’, which are “celaka”, “puki mak”, and “sial”.(30)

The earlier examples also set forth several examples of deletion and neutralisation strategies in the subtitles. This generally indicates two points of reflection – first, the findings confirm the notion by Diaz-Cintas and Remael(7) that in AVT, explicit taboo loads are commonly mitigated and of less quality in the target texts. Secondly, this, among other things, signals that the pragmatic factors of the Malaysian language and culture are still prevalent and deemed relevant to be retained by translators, even though the streaming platform maintains no content and language restrictions.

While this may not be directly related to the research objectives, the analysis also identified issues of taboo reference comprehension by subtitlers. For example, the “the shit” phrase that is repeatedly mentioned at the end of the second episode of this TV series refers to a positive meaning, as exemplified in Kory’s dialogue, “Now, if something is the shit, and this is how you differentiate between the good and the bad, that means it is excellent…” Nevertheless, the excerpted phrase failed to identify the reference and translated it as “masalah” (literally ‘problem’) (Jika sesuatu itu masalah dan ini cara awak membezakan antara baik dan buruk, itu bermakna ia bagus). Apart from that, the phrase is also translated negatively using different terms, such as “tak guna” (useless) and “sial” (cursed), which may ultimately alter the audience’s overall understanding.

Despite yielding valuable insights into taboo subtitling practices, this study is also constrained by several notable limitations. Firstly, the research is based solely on two episodes of a single TV series, which limits the ability to generalize the findings to other AV products. Secondly, the forms of taboo language analysed within the data include instances used in informative contexts, which may not be considered taboo in certain cultural settings. The overlap between offensive and non-offensive uses of language may in turn complicate the interpretation of subtitling strategies and may vary significantly across different cultural backgrounds. The study also notes the importance to incorporate other relevant fields of study in the analysis, such as communication, film studies(31), and product distribution and marketing(32,33) in ensuring a comprehensive output of the analysis.

CONCLUSION

This study highlights the complexities of translating swearwords in AV contexts by focusing on the English swearwords of ‘fuck’ and ‘shit’ in Malay subtitles. The findings suggest that subtitlers rely on both creative and formal strategies to navigate both linguistic and cultural challenges by employing a variety of translation strategies. The study also found that these translation choices are influenced by socio-pragmatic factors, reflecting the nuanced nature of swearword usage in the target language.

The present study also raises important considerations regarding the subtitlers’ ability to accurately identify and comprehend the semantic depth of swearwords. Given the lack of censorship on online streaming platforms such as Netflix, a balance between linguistic accuracy and cultural appropriateness is thus of essence in negotiating multimodal complexities, and in turn, determining how the exercised strategies impact audience reception and understanding.

REFERENCES

1. Vance C. Multilingualism: An increasing necessity in an interconnected world [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2023 Apr 30]. Available from: https://medium.com/@cartervance/multilingualism-an-increasing-necessity-in-an-interconnected-world-4cd4b7b701c

2. Zarzycki Ł. The anatomy of Polish offensive words: A sociolinguistic exploration. Vol. 53. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2024.

3. visitjeju.net. Jeju Loveland [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 30]. Available from: https://www.visitjeju.net/en/detail/view?contentsid=CONT_000000000500550

4. Wheelan B. Youtube. 2016 [cited 2016 Oct 1]. Laughs in Translation - Denmark. Available from: https://goo.gl/p6H03H

5. Loughrey C. Independent. 2016 [cited 2017 Jan 1]. Deadpool gets banned in China due to violence, nudity, and graphic language. Available from: https://goo.gl/FhQVio

6. Jafwan Jaafar. They’re a no-show: Major movies banned in Malaysia [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2024 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/leisure/2016/02/25/theyre-a-no-show-major-movies-banned-in-malaysia/

7. Díaz Cintas J, Remael A. Subtitling: Concepts and practices. New York: Routledge; 2021.

8. Meagher B, Bachner R, Farah M, Farrell J, Belew B, Blackstone B. The History of Swear Words [TV Series]. Netflix; 2021.

9. Allan K, Burridge K. Forbidden words: Taboo and the censoring of language. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

10. Wajnryb R. Expletive deleted: A good look at bad language. Free Press; 2005.

11. Parini I. Taboo and translation in audiovisual works. In: Susana Bayo Belenguer, Eilean Ni Chuilleanain, Cormac O Cuilleanain, editors. Translation Right or Wrong. Four Courts Press; 2013. p. 149–61.

12. Reynolds R, Kinberg S, Donner Shulen L (Producer), Miller T (Director). Deadpool [Motion Pictures]. United States of America: Motion Pictures; 2016.

13. Trudgill P. Sociolinguistics: An introduction to language and society. 4th ed. London: Penguin Group; 2000.

14. Antonini R, Bucaria C, Senzani A. “It’s a priest thing, you wouldn’t understand: Father Ted goes to Italy.” Antares Umorul –O Nou Stiinta VI. 2003;(Special Issue):26–30.

15. Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim, Hasuria Che Omar. The strategies of subtitling humour in Deadpool: Retain, eliminate or add? GEMA Online Journal of Language Studies. 2021;21(1):186–203.

16. Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim, Muhammad Faizal Matalib, Iliya Nurul Iman Mohd Ridzuan. The subtitling of humour in Deadpool: A reception study. Opcion. 2019;35(Special Issue):1264–90.

17. Ministry of Home Affairs of Malaysia. Garis panduan penapisan filem 2024 [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://ilpf.moha.gov.my/assets/layouts/layout/img/GarisPanduanPenapisanFilem2024.pdf

18. G. Prakash. Malay Mail. 2019 [cited 2023 Apr 30]. BN lawmaker concerned over sex scenes, LGBT elements on Netflix. Available from: https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2019/03/27/bn-lawmaker-concerned-over-sex-scenes-lgbt-elements-on-netflix/1737089

19. Radzi Razak. Malay Mail. 2019 [cited 2023 Apr 30]. Finas calls for Putrajaya to censor Netflix here. Available from: https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2019/11/16/finas-calls-for-putrajaya-to-censor-netflix-here/1810472

20. Feride Hikmet Atak. Berita Harian Online. 2019 [cited 2023 Apr 30]. Selesai dulu masalah industri filem tempatan - Sharifah Amani. Available from: https://www.bharian.com.my/hiburan/lain-lain/2019/11/630046/selesai-dulu-masalah-industri-filem-tempatan-sharifah-amani?fbclid=IwAR3JJtCnZSktDIii_HNVkeMA0zRNGhsPB5MxPhISPkyEBfW2Zk71zHE8ITk

21. KiniTV. KiniTV. 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 30]. Annuar: Malaysia does not have “tools” to censor sensitive content on Netflix. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SqIM5HfpLDU&ab_channel=KiniTV

22. Ávila-Cabrera JJ. The subtitling of offensive and taboo language: A descriptive study. Universidad Nacional De Educación A Distancia; 2014.

23. Wu S. Subtitling swear words from English into Chinese: A corpus-based study of Big Little Lies. Open J Mod Linguist. 2021;11(02):277–90.

24. Abu-Rayyash H, Haider AS, Al-Adwan A. Strategies of translating swear words into Arabic: a case study of a parallel corpus of Netflix English-Arabic movie subtitles. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2023 Jan 30;10(1):39.

25. Abdelaal NM, Al Sarhani A. Subtitling strategies of swear words and taboo expressions in the movie “Training Day.” Heliyon. 2021 Jul;7:1–9.

26. Al-Jabri H, Allawzi A, Abushmaes A. A comparison of euphemistic strategies applied by MBC4 and Netflix to two Arabic subtitled versions of the US sitcom How I Met Your Mother. Heliyon. 2021 Feb;7(2):1–8.

27. Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim, Khairul Faiz Alimi. Subtitling Malay taboo language into English: The case of The Assistant (2022). RENTAS: Jurnal Bahasa, Sastera dan Budaya [Internet]. 2024 Jul 16 [cited 2024 Sep 20];3(1):119–40. Available from: https://e-journal.uum.edu.my/index.php/jbsb/article/view/23503

28. Díaz-Pérez FJ. Translating swear words from English into Galician in film subtitles. Babel Revue internationale de la traduction / International Journal of Translation. 2020 Jun 24;66(3):393–419.

29. Pusat Rujukan Persuratan Melayu. Pusat Rujukan Persuratan Melayu. 2023 [cited 2023 Apr 30]. Fuck. Available from: https://prpm.dbp.gov.my/Cari1?keyword=fuck&d=394756&#LIHATSINI

30. Pusat Rujukan Persuratan Melayu. Pusat Rujukan Persuratan Melayu. 2023 [cited 2023 Apr 30]. Shit. Available from: https://prpm.dbp.gov.my/Cari1?keyword=shit&d=394756&#LIHATSINI

31. Pérez-González L. Audiovisual translation: Theories, methods and issues. Oxon: Routledge; 2014.

32. Kamarudin MAI, Yusof MS, Ramli A, Othman S, Hasan H, Jaaffar AR, et al. The issues and challenges of diversification strategy in multiple industries: The case of Kental Bina Sdn. Bhd. PaperASIA [Internet]. 2024 May 13 [cited 2024 Aug 7];40(3b):48–58. Available from: https://www.compendiumpaperasia.com/index.php/cpa/article/view/94

33. Abaidah TNABT, Kamarudin MAI Bin, Kamarruddin NAB. The model of entrepreneurial marketing (EM) among agropreneurs in the emerging markets: A conceptual framework. UCJC Business and Society Review (formerly known as Universia Business Review) [Internet]. 2024 Jan 5 [cited 2024 Aug 7];21(80). Available from: https://journals.ucjc.edu/ubr/article/view/4619

FINANCING

This work was supported by Universiti Utara Malaysia through the University Research Grant Scheme (S/O Code: 21168).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim.

Data curation: Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim.

Formal analysis: Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim.

Research: Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim.

Methodology: Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim.

Project management: Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim.

Resources: Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim.

Software: Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim.

Supervision: Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim.

Validation: Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim.

Display: Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim.

Drafting - original draft: Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Mohamad Zakuan Tuan Ibharim.