doi: 10.56294/sctconf2024.1284

ORIGINAL

Social Exclusion and Consumer Preference for Crowded Shopping Environments: The Moderating Role of Time Perspective

Exclusión social y preferencia de los consumidores por los entornos comerciales abarrotados: El papel moderador de la perspectiva temporal

1Loyola Institute of Business Administration (LIBA). Chennai, India.

Cite as: Christu Raja M. Social Exclusion and Consumer Preference for Crowded Shopping Environments: The Moderating Role of Time Perspective. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2024; 3:.1284. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2024.1284

Submitted: 18-04-2024 Revised: 16-07-2024 Accepted: 02-11-2024 Published: 03-11-2023

Editor: Dr.

William Castillo-González ![]()

ABSTRACT

Introduction: this study investigates how social exclusion influences consumer preferences for crowded shopping environments and examines the moderating role of time perspective. Specifically, it explores the mediating role of social connectedness and how present hedonism and fatalism impact these preferences.

Method: three experimental studies tested the hypotheses. Participants were randomly assigned to social exclusion or inclusion conditions, and their preferences for crowded environments were measured. Time perspective (present hedonism and fatalism) and social connectedness were also assessed.

Results: results show that socially excluded consumers prefer crowded environments to fulfill their social connectedness needs. Present hedonism intensifies this preference, while present fatalism diminishes it. The findings demonstrate the significant role of social exclusion and time perspective in shaping consumer behavior.

Practical Implications: these findings provide actionable strategies for retailers to design environments that address the psychological needs of socially excluded consumers. Retailers can use these insights to create targeted marketing strategies, especially in a post-pandemic context, where social interactions are evolving.

Originality/Value: this study offers new insights into the psychological mechanisms behind consumer behavior in response to social exclusion. By integrating Belongingness Theory and Time Perspective Theory, it deepens the understanding of how social exclusion drives consumer preferences for crowded environments, highlighting the moderating effects of present hedonism and fatalism.

Keywords: Social Exclusion; Consumer Behavior; Retail Crowding; Time Perspective; Social Connectedness.

RESUMEN

Introducción: este estudio investiga cómo influye la exclusión social en las preferencias de los consumidores por los entornos comerciales abarrotados y examina el papel moderador de la perspectiva temporal. En concreto, explora el papel mediador de la conectividad social y cómo el hedonismo y el fatalismo actuales influyen en estas preferencias.

Método: tres estudios experimentales pusieron a prueba las hipótesis. Los participantes fueron asignados aleatoriamente a condiciones de exclusión o inclusión social, y se midieron sus preferencias por los entornos concurridos. También se evaluó la perspectiva temporal (hedonismo presente y fatalismo) y la conexión social.

Resultados: los resultados muestran que los consumidores socialmente excluidos prefieren los entornos abarrotados para satisfacer sus necesidades de conexión social. El hedonismo presente intensifica esta preferencia, mientras que el fatalismo presente la disminuye. Los resultados demuestran el importante papel que desempeñan la exclusión social y la perspectiva temporal en la configuración del comportamiento de los consumidores.

Implicaciones prácticas: estas conclusiones proporcionan estrategias prácticas para que los minoristas diseñen entornos que respondan a las necesidades psicológicas de los consumidores socialmente excluidos. Los minoristas pueden utilizar estos conocimientos para crear estrategias de marketing específicas, especialmente en un contexto pospandémico, en el que las interacciones sociales están evolucionando.

Originalidad/valor: este estudio ofrece nuevas perspectivas sobre los mecanismos psicológicos que subyacen al comportamiento de los consumidores en respuesta a la exclusión social. Al integrar la Teoría de la Pertenencia y la Teoría de la Perspectiva Temporal, profundiza en la comprensión de cómo la exclusión social impulsa las preferencias de los consumidores por los entornos masificados, destacando los efectos moderadores del hedonismo y el fatalismo actuales.

Palabras clave: Exclusión Social; Comportamiento del Consumidor; Multitud en Comercios Minoristas; Perspectiva Temporal; Pertenencia Social.

INTRODUCTION

Social exclusion, the feeling of being ignored or ostracized by others, poses a significant threat to individuals’ fundamental social needs, including belongingness, self-esteem, control, and meaningful existence.(1) This experience triggers both social and physical pain,(2) driving a strong motivation to regain social connections. To cope with exclusion, individuals often engage in behaviors aimed at restoring their sense of belonging, such as altering their consumption patterns to signal their desire for social affiliation.(3,4) This phenomenon has important implications for understanding consumer behavior, particularly in the context of retail environments.

Previous research has shown that consumers who feel excluded may select brands and products that reflect aspirational social groups or engage in conspicuous consumption to signal their social value.(5) These consumption choices act as compensatory mechanisms to mitigate feelings of rejection. For example, the desire for social approval can significantly drive consumer preferences, influencing the selection of products that symbolize group membership.(6) However, the role of retail crowding—a crucial factor in shaping shopping experiences—remains underexplored in the context of social exclusion. Retail crowding refers to the presence of a large number of people in a shopping environment, which can elicit diverse consumer responses.(7) While crowding is often associated with negative outcomes, such as stress and avoidance behavior,(8) it may also serve as a cue for social interaction and affiliation, especially for those seeking to reestablish their sense of belonging. For socially excluded individuals, crowded environments may provide a heuristic for potential social contact, thereby attracting those looking to reestablish their social bonds.(9)

While there is a growing body of literature on the role of social exclusion in shaping consumer behavior, there is limited understanding of how socially excluded individuals respond to retail crowding. Previous studies have often focused on the negative aspects of crowding, such as avoidance behavior or stress,(8) but some research indicates that certain consumers may actively seek out crowded environments to satisfy their social needs.(7) This inconsistency suggests the importance of individual differences, such as the experience of social exclusion, in shaping consumer responses to crowding.

One critical but underexplored factor that may influence this relationship is time perspective. Time perspective refers to how individuals mentally organize and relate to their experiences across past, present, and future dimensions.(10) It has been shown to significantly affect how people cope with social rejection. For instance, individuals with a present hedonistic orientation—those who focus on immediate pleasure and experiences—may be more inclined to seek crowded environments as a means of fulfilling their immediate need for social interaction. Conversely, those with a present fatalistic orientation, who perceive their situation as fixed and unchangeable, may exhibit less motivation to engage with crowded spaces. Integrating time perspective into the study of social exclusion and retail crowding offers a nuanced understanding of how temporal factors influence consumer preferences, contributing to a clearer picture of how social exclusion drives behavior in retail contexts.

This study aims to address these gaps by investigating how social exclusion influences consumer preference for crowded shopping environments and examining the moderating role of time perspective. Specifically, it explores whether the need for social connectedness mediates the relationship between social exclusion and preference for crowded environments, and how this relationship is moderated by present hedonism and fatalism. By exploring these dynamics, this research not only extends existing frameworks but also offers a novel perspective on how consumers’ temporal orientations influence their response to social exclusion in retail environments.

This research makes several key contributions. First, it extends the understanding of social exclusion in retail contexts by identifying the conditions under which crowding becomes attractive to excluded consumers. Second, it offers a novel integration of Belongingness Theory and Time Perspective Theory, providing deeper insights into the psychological processes driving consumer preferences. While earlier research has mainly focused on the compensatory behaviors of excluded individuals, such as brand preference and conspicuous consumption, (5,6) this study highlights a new dimension: the role of crowded environments as a heuristic for social connection. Finally, it presents actionable strategies for retailers and marketers, highlighting how they can create shopping environments that resonate with the emotional and psychological needs of socially excluded consumers. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, where social interactions have been disrupted and consumer behaviors have shifted, understanding how social exclusion affects preferences for retail environments is particularly relevant. By uncovering how and why socially excluded consumers gravitate towards crowded spaces, this study contributes not only to academic discourse but also to practical strategies for retailing in a post-pandemic society. These findings are particularly relevant for marketers designing post-pandemic retail environments that cater to consumers’ emotional and psychological needs, especially those who may feel socially disconnected.

Theoretical Framework

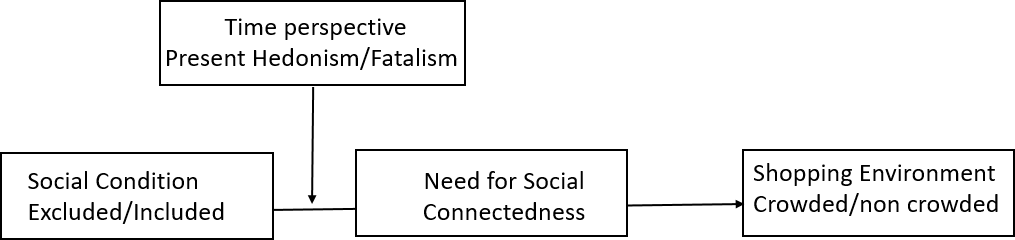

This study integrates Belongingness Theory and Time Perspective Theory. Belongingness Theory posits that individuals have an inherent need to form social bonds, which intensifies under social exclusion.(11) Time Perspective Theory suggests that individuals’ temporal orientation influences their coping mechanisms and decision-making processes.(10) Together, these theories explain how social exclusion and time perspective interact to shape consumer behavior in crowded retail environments (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Theoritical Framework

Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

The Need for Social Connectedness

Social exclusion triggers social and physical pain, both processed by similar neural pathways.(2) This dual pain increases the need for social connectedness.(3) In retail settings, crowding can serve as a cue for social interaction, offering socially excluded individuals a chance to mitigate feelings of rejection.(9) Human crowding, which involves the presence of many customers, is more directly linked to social perception and the feeling of connectedness.(7) Research indicates that human crowding can enhance perceptions of social closeness and increase purchase intentions.(12) Hence, socially excluded individuals may see crowded environments as opportunities for connection.

H1: Socially excluded consumers prefer more crowded shopping environments than socially included ones.

Social Exclusion and Retail Crowding

Social exclusion leads individuals to engage in compensatory behaviors, such as conspicuous consumption, to signal their desire for social affiliation.(5,6) Belongingness Theory posits that individuals have an innate drive to form social bonds, particularly when excluded.(11) Crowded retail spaces can act as cues for social interaction, offering excluded consumers a sense of belonging.(13) Thus, crowding can be perceived as a favorable setting for socially excluded individuals to fulfill their need for connectedness.

H2: Socially excluded individuals will have a stronger need for social connectedness, mediating the relationship between social exclusion and preference for crowded shopping environments.

Social Exclusion and Time Perspective

Time Perspective Theory provides insight into how individuals cope with social rejection. Present hedonism involves seeking immediate pleasure and can lead excluded individuals to engage in behaviors that offer instant gratification, such as preferring crowded environments for social interaction.(14) Present fatalism, on the other hand, denotes a belief in a predetermined future, reducing the motivation to seek social connection in crowded spaces. This distinction highlights the moderating role of time perspective in the relationship between social exclusion and consumer preferences.

H3: The impact of social exclusion on preference for a crowded shopping environment is moderated by time perspective, with present hedonism increasing and present fatalism decreasing the likelihood of seeking crowded environments.

METHOD

Three experimental studies tested these hypotheses. Studies 1 and 2 utilized Amazon Mechanical Turk, while Study 3 used Qualtrics. Participants received monetary compensation. Study 1 examined the direct effect of social exclusion on preferences for crowded environments. Study 2 investigated the mediating role of social connectedness. Study 3 explored the moderating effect of time perspective, specifically present hedonism and present fatalism.

Study 1: Development And Results

Study 1 employed a single-factor between-subjects design with 175 participants (52 % male, 48 % female) recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk. The participants were randomly assigned to either the social exclusion condition or the social inclusion condition. The sample size was determined based on a priori power analysis using G*Power, which indicated that a sample of at least 150 participants would be necessary to detect medium-to-large effect sizes with 80 % power.(15) Participants were compensated with a small monetary reward for their time and participation.

Participants first read a hypothetical social media scenario designed to manipulate their feelings of social exclusion or inclusion. In the exclusion condition, participants were asked to imagine and write about a time when they were socially rejected, ignored, or excluded. In contrast, participants in the inclusion condition were asked to write about a time when they were socially accepted or included. Following the writing task, participants completed a manipulation check by rating their feelings of social inclusion/exclusion using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not included at all, 7 = very included). After completing the manipulation check, participants were presented with a second task where they were asked to indicate their shopping environment preference. They viewed images depicting different crowding levels in a shopping mall and were asked to select their preferred shopping environment. The images were pretested to ensure they reliably conveyed varying levels of crowding. Participants’ preference for crowded shopping environments was measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = least crowded, 7 = most crowded). In addition, demographic variables (e.g., age, gender) were collected to control for potential confounds.

The manipulation check confirmed the effectiveness of the social exclusion manipulation. Participants in the exclusion condition reported significantly lower feelings of inclusion (M = 2,44, SD = 1,20) compared to participants in the inclusion condition (M = 5,40, SD = 1,33), F(1,173) = 106,05, p < ,001. As hypothesized (H1), the analysis revealed that participants in the exclusion condition showed a significantly stronger preference for crowded shopping environments (M = 3,69, SD = 0,56) than those in the inclusion condition (M = 2,09, SD = 0,70), F(1,173) = 127,81, p < ,001. This finding suggests that social exclusion increases consumers’ inclination toward crowded spaces, likely driven by their need for social connection.

Study 2: Development And Results

Study 2 employed a 2x2 between-subjects design with 147 participants (55,4 % male, 44,6 % female), also recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk. Participants were again randomly assigned to either the social exclusion or inclusion condition, and an additional control variable—perceived quality of service—was measured to account for potential variations in participants’ shopping environment preferences. Similar to Study 1, participants were compensated for their participation.

The procedure began with the same social exclusion/inclusion manipulation used in Study 1. Participants recalled personal experiences of either exclusion or inclusion based on the provided prompt. After completing the manipulation task, participants were asked to rate their feelings of exclusion or inclusion using a 7-point Likert scale. Following the manipulation check, participants were shown images depicting various levels of crowding in shopping environments, and their preferences were recorded. In this study, we also introduced the mediator variable, social connectedness, which was measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) with items adapted from Lee and Robbins(16), (e.g., I feel disconnected from the world around me). The dependent variable was participants’ preference for crowded shopping environments, measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = least crowded, 7 = most crowded). In addition, perceived social connectedness was measured as a mediator, and perceived quality of service was included as a control variable. Demographic data were collected as well.

The manipulation check was successful, with participants in the exclusion condition reporting a stronger feeling of rejection (M = 5,33, SD = 1,83) than those in the inclusion group (M = 4,45, SD = 1,05; F(1, 145) = 72,92, p < ,001). The impact of social exclusion on shopping environment preference was significant (F(1, 145) = 35,24, p < ,001). Excluded participants showed a stronger preference for crowded environments (M = 3,93, SD = 0,27) than included participants (M = 2,70, SD = 1,03). Mediation analysis using PROCESS Model 4 by Hayes,(17) with 5,000 bootstrap samples revealed a significant indirect effect of social exclusion on preference for crowded environments through social connectedness (b = 0,49, SE = 0,24, 95 % CI [0,0721, 0,9990]), supporting H2. The direct effect of social exclusion on shopping preference became insignificant when accounting for social connectedness, indicating full mediation.

Study 3: Development And Results

Study 3 employed a 2x2 factorial design to investigate the moderating effect of time perspective on the relationship between social exclusion and shopping environment preference. A total of 195 participants (49 % male, 51 % female) were recruited from Qualtrics’ online participant pool, ensuring a more diverse demographic compared to Studies 1 and 2. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: social exclusion/present hedonism, social exclusion/present fatalism, social inclusion/present hedonism, and social inclusion/present fatalism.

As in the previous studies, participants first completed the social exclusion or inclusion manipulation by recalling a personal experience of social rejection or acceptance. After the manipulation, participants were asked to complete a series of questionnaires assessing their time perspective using Zimbardo and Boyd’s (1999) 15-item Time Perspective Inventory. This scale assesses individuals’ temporal orientations, with subscales for present hedonism (e.g., “I live life for today”) and present fatalism (e.g., “My future is predestined”). Next, participants indicated their preference for a shopping environment by choosing from images depicting different levels of crowding, as in the previous studies. The key dependent variable remained preference for crowded shopping environments, measured using the same 7-point Likert scale. In this study, participants’ time perspective (present hedonism and present fatalism) was included as a moderator, and manipulation checks for both the social exclusion and time perspective conditions were conducted.

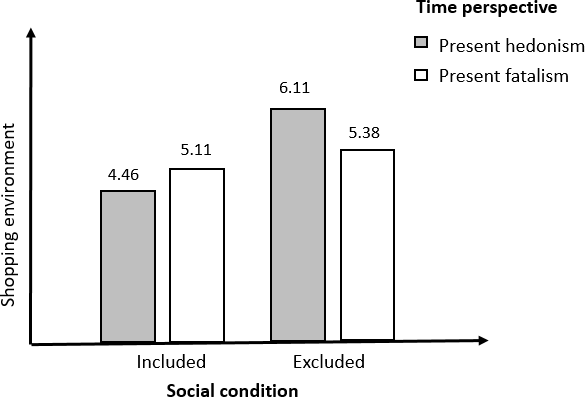

Moderation analysis using PROCESS Model 1 by Hayes(17) revealed a significant interaction effect between social exclusion and present hedonism on preference for crowded environments (B = 0,36, t = 3,80, p < ,001). Specifically, under the present hedonism condition, excluded participants preferred crowded environments more than included participants (B = 0,21, t = 7,54, p < ,001). However, in the present fatalism condition, the differences in preference were non-significant (B = 0,28, t = 0,95, p = ,347).

A moderated mediation analysis using PROCESS Model 7 with 5,000 bootstrap samples (Hayes, 2018) showed that present hedonism significantly moderated the mediation effect of social connectedness (b = 0,59, SE = 0,24, 95 % CI [0,17, 1,11]), confirming H3. The relationship between social exclusion and preference for crowded environments was strongest for participants with a present hedonistic time perspective (see figure 2)

Figure 2. Moderated Mediation effect of Time Perspective

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study highlight how social exclusion influences consumers’ preference for crowded shopping environments and the role of time perspective in moderating this effect. Consistent with prior research on social exclusion and compensatory behaviors,(9,11) socially excluded individuals in our study demonstrated a stronger preference for crowded environments. This aligns with Machleit et al.(7) who found that human crowding can enhance perceptions of social closeness. Our study extends this understanding by illustrating how socially excluded consumers view crowded spaces as opportunities to restore social connectedness, reinforcing the idea of crowding as a cue for social interaction.(12) The mediating role of social connectedness aligns with Baumeister and Leary’s Belongingness Theory(11), suggesting that individuals experiencing social exclusion seek to fulfill their fundamental need to belong. These results are consistent with Williams’(3) findings, which showed that exclusion triggers efforts to re-establish social bonds. Our findings also build on the work of Thomas and Saenger,(9) indicating that retail crowding can be perceived as a space for potential social affiliation. The moderating effect of time perspective reveals that individuals with a present hedonistic orientation are more likely to prefer crowded environments, as they seek immediate social gratification. This echoes Zimbardo and Boyd’s (10) Time Perspective Theory, which posits that present hedonists prioritize experiences that fulfill immediate needs. Conversely, those with a present fatalistic orientation, who perceive their future as fixed, showed no significant preference for crowded environments, indicating a lack of motivation to change their social circumstances.

CONCLUSIONS

This study offers a new perspective on how and why social exclusion leads to a preference for a crowded shopping environment by linking social exclusion and time perspectives in the context of consumers’ consumption behaviors. The influence of time perspective on consumers’ decision-making will help marketers to make informed decisions and align their advertising and marketing message to harvest more profits. For instance, the present hedonistic time perspective will impact conspicuous green consumption when people encounter a threat to their social relationships. As social exclusion is ubiquitous, marketing strategies like singles day, as opposed to valentine’s day, will be beneficial. In the context of covid-19, where preventive consumption pattern is vivid, socially excluded will switch their preference for preservative consumption in crowded shopping environments.

Theoretical Contributions

This study makes several theoretical contributions to the fields of social psychology and consumer behavior. Firstly, it extends the literature on social exclusion by demonstrating how exclusion influences consumer preferences for crowded shopping environments, mediated by the need for social connectedness. While previous research has shown that social exclusion can lead to compensatory consumption behaviors,(5,6) this study specifically highlights how crowded retail environments serve as a heuristic for social affiliation, offering a novel perspective on how excluded individuals navigate their need for connection in public settings.(9) Secondly, this research integrates Belongingness Theory by Baumeister and Leary(11) with Time Perspective Theory by Zimbardo and Boyd(10) to provide a deeper understanding of consumer behavior. By examining the moderating role of present hedonism and present fatalism, the study contributes to the growing body of literature on temporal orientation and its impact on decision-making.(14) It shows that socially excluded individuals with a present hedonistic orientation are more likely to seek immediate social gratification in crowded spaces, adding nuance to our understanding of how time perspective influences consumer behavior in the context of social exclusion.

Practical Contributions and Managerial Implications

This study’s findings have practical implications for retailers and marketers, especially in the context of post-pandemic retailing. By understanding that socially excluded consumers exhibit a preference for crowded environments, marketers can design advertising and promotional strategies that emphasize social presence and connection. For instance, marketing campaigns that create a sense of community or leverage social events (e.g., “Singles’ Day”) can attract consumers seeking affiliation.(18) Moreover, by recognizing the role of present hedonism, retailers can tailor their in-store experiences to cater to consumers’ desire for immediate pleasure and social interaction. For example, incorporating engaging activities or sensory elements within crowded spaces can enhance the shopping experience for socially excluded consumers, making them more likely to remain in-store and make purchases.(12) Additionally, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, this research suggests that socially excluded consumers may shift their preferences toward preservative consumption in crowded environments. Retailers can respond by creating safe yet socially engaging shopping experiences, such as controlled crowd events or limited-capacity in-store gatherings that allow consumers to connect while maintaining health and safety guidelines.(13) By understanding the psychological drivers behind consumer preferences, marketers can better align their strategies with the emotional and temporal needs of their target audience.

Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations suggest directions for future research. First, the hypothetical social exclusion scenario used may not fully capture the complexity of real-world exclusion experiences. Future studies could employ field experiments or longitudinal approaches to better understand how social exclusion affects consumer behavior over time.(19) Second, this study focused on present hedonism and fatalism in time perspective. Future research could examine other temporal orientations, such as future or past perspectives, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of their role in consumer decision-making.(20) Third, the sample, drawn from online platforms, may limit the generalizability of the findings. Cross-cultural studies could explore how social exclusion and time perspective influence consumer behavior in different cultural contexts, as cultural dimensions such as collectivism and individualism shape social behavior and consumption patterns.(21) Finally, this study examined retail crowding, but future research could investigate how social exclusion impacts consumer preferences in digital environments, where crowding may be perceived differently, especially in the context of growing online retail spaces.(22)

REFERENCES

1. Lu S, Sinha J. Feeling left out: The dynamic relationship between social exclusion and brand preference. J Consum Psychol. 2017;27(4):462–71.

2. Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD. Why rejection hurts: A common neural alarm system for physical and social pain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;8(7):294–300.

3. Williams KD. Ostracism: The power of silence. New York: Guilford Press; 2001.

4. Mead NL, Baumeister RF, Stillman TF, Rawn CD, Vohs KD. Social exclusion causes people to spend and consume strategically in the service of affiliation. J Consum Res. 2011;37(5):902–19.

5. Chen Z, Williams KD, Fitness J, Newton NC. When hurt will not heal: Exploring the capacity to relive social pain. Psychol Sci. 2017;19(8):789–95.

6. Gao L, Wheeler SC, Shiv B. The “shaken self”: Product choices as a means of restoring self-view confidence. J Consum Res. 2009;36(1):29–38.

7. Machleit KA, Kellaris JJ, Eroglu SA. Human versus spatial dimensions of crowding perceptions in retail environments: A note on their measurement and effect on shopper satisfaction. Mark Lett. 1994;5(2):183–94.

8. Eroglu SA, Harrell GD. Retail crowding: Theoretical and strategic implications. J Retailing. 1986;62(4):346–63.

9. Thomas T, Saenger C. Retail crowding, social connection, and coping behaviors: A dynamic approach. J Consum Psychol. 2020;30(4):708–22.

10. Zimbardo PG, Boyd JN. Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(6):1271–88.

11. Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(3):497–529.

12. Esmark CL, Noble SM. Retail crowding and customer satisfaction: The role of interpersonal closeness and shopping satisfaction in a social crowd. J Retail Consum Serv. 2018;40:203–12.

13. Su L, Wan C, Fan X. Human crowding and tourists’ shopping experiences in the Chinese market. Tour Manag. 2019;71:68–79.

14. Suszek H, Zaleskiewicz T, Gasiorowska A. Time perspective and social exclusion: Differences between negative and positive exclusion experiences. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2019;85:103881.

15. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2020;52(2):689–701.

16. Lee RM, Robbins SB. Measuring belongingness: The Social Connectedness and the Social Assurance scales. J Couns Psychol. 1995;42(2):232–41.

17. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2017.

18. Huang Y, Liu W, Kandampully J, Fan M. How consumers perceive singles day in China: Conspicuous consumption or self-gift? J Retail Consum Serv. 2019;50:147–56.

19. Poon KW, Kwok J. Can virtual reality enhance the experience of social exclusion? The role of metacognitive processes in immersive environments. J Interact Mark. 2021;54:50–62.

20. Shen L, Ly PTM, Palm R. How temporal framing influences consumer behavior: A meta-analysis. J Consum Psychol. 2021;31(4):644–61.

21. Kim J, Baker MA. Cross-cultural influences on social exclusion and consumer behavior: A comparative study. J Bus Res. 2020;120:469–80.

22. Verhoef PC, Broekhuizen T, Bart Y, Bhattacharya A, Qi Dong J, Fabian N, Haenlein M. Digital transformation in retailing: A framework and research agenda. J Bus Res. 2021;122:889–901.

FINANCING

No financing for the article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Christu Raja, M.

Data curation: Christu Raja, M.

Formal analysis: Christu Raja, M.

Research: Christu Raja, M.

Methodology: Christu Raja, M.

Project management: Christu Raja, M.

Resources: Christu Raja, M.

Software: Christu Raja, M.

Supervision: Christu Raja, M.

Validation: Christu Raja, M.

Display: Christu Raja, M.

Drafting - original draft: Christu Raja, M.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Christu Raja, M.