Category: Arts and Humanities

ORIGINAL

Situational teaching of emergency language curriculum constructs

Enseñanza situacional de construcciones curriculares de lenguaje de emergencia

1Chinese International College, Dhurakij Pundit University, Bangkok, 10210, Thailand.

2Humanities College, Kunming Arts & Sciences College, Kunming, Yunnan, 650222, China.

Cite as: Zhu A, Fei Chen1 P. Situational teaching of emergency language curriculum constructs. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2024; 3:1095. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf20241095

Submitted: 25-01-2024 Revised: 05-04-2024 Accepted: 11-07-2024 Published: 12-07-2024

Editor: Dr.

William Castillo-González ![]()

ABSTRACT

In the situation of sudden disasters, linguistic communication became a key part of disaster research. Both China and the West emphasized the importance of disaster education, and the development of emergency language courses in universities has become an important concern in the above context. This study constructs an emergency language course based on the situational teaching theory to improve the emergency language competence of Chinese university students. Firstly, the curriculum was designed using the situational teaching method, based on which the 4 units of the emergency situation design were used to prepare the draft of the curriculum. Then the content validity of the curriculum was reviewed by experts, finally form the capability indicators of emergency language talent and the simulation-oriented emergency language curriculum.

Keywords: Emergency Language; Situational Teaching; Curriculum; Talent Capability Indicators.

RESUMEN

En situaciones de desastres repentinos, la comunicación lingüística se convirtió en una parte clave de la investigación de desastres. Tanto China como Occidente enfatizaron la importancia de la educación sobre desastres, y el desarrollo de cursos de idiomas de emergencia en las universidades se ha convertido en una preocupación importante en el contexto mencionado. Este estudio construye un curso de idiomas de emergencia basado en la teoría de la enseñanza situacional para mejorar la competencia lingüística de emergencia de los estudiantes universitarios chinos. En primer lugar, se diseñó el currículo utilizando el método de enseñanza situacional, a partir del cual se utilizaron las 4 unidades del diseño de situaciones de emergencia para elaborar el borrador del currículo. Luego, los expertos revisaron la validez del contenido del plan de estudios, finalmente formaron los indicadores de capacidad del talento lingüístico de emergencia y el plan de estudios de lenguaje de emergencia orientado a la simulación.

Palabras clave: Lenguaje de Emergencia; Enseñanza Situacional; Currículo; Indicadores de Capacidad de Talento.

INTRODUCTION

In situations where natural or man-made disasters occured, O’Brien et al. (2018) introduced the concept of crisis translation, argued that clear, timely and accurate information was the strategic and operational key to an effective response to disasters. It is evident that language is a matter of life in emergencies and disasters, and thus barriers to and effective methods of communicating linguistically in disaster contexts were a central concern of current disaster research, practice and policy (Uekusa, 2019). The New Crown epidemic as a public health emergency brought normal social processes to a virtual standstill and drastically changed people’s lives, including their linguistic lives (Feldhege et al., 2021). As part of language life, emergency language services had received unprecedented attention (Li, 2020; O’Brien, 2019; Shen, 2020; Zheng, 2020). The lack of high-quality emergency language service talents, and the lack of the necessary emergency knowledge reserves and the emergency rescue practical training experience (Cai, 2020; Li, 2020; Teng, 2020; Xiong et al., 2023), and the lack of understanding of industry terminology which made it difficult to carry out the work independently (Liu & Lei, 2019), had all exposed the imperfections in the mechanism and system of the emergency language service, the lack of emergency language service personnel training that should increase the construction efficiency of emergency language courses and other problems (Wang et al., 2020a). Disaster education can be integrated with other disciplines, one of which is language learning (Ramadhan et al., 2019). In order to prepare students to acquire the ability to respond to disasters, disaster education in universities is essential for raising awareness and taking action on disaster preparedness among students and their communities (Boon & Pagliano, 2014). Therefore, Li (2021) suggested that it was very important for universities to educate on emergency language services, including vocational colleges should also paid attention to using their majors to educate on emergency language services, and that there should be a professional development of emergency language and an establishment of emergency linguistics, which should be remedied as soon as possible.

In August 2021, the Ministry of Education of China approved Beijing Language and Culture University to independently set up the major of “international language service” under the first-level discipline of foreign language and literature. The language service which has been discussed for many years in the academia, officially entered into the academic education system of the institution, which means that the discipline of emergency language and the curriculum have really entered into the stage of history. Wang et al. (2020b) pointed out that, for universities, foreign language disciplines should practically think about and adjust their disciplines and professional settings in terms of actual needs, set up additional language service majors and cultivated emergency language service talents. Li (2021) proposed that in universities, majors can incorporate emergency language into their course content or even into their training specifications, which is a viable approach to curriculum building. Emergency language curriculum is an emerging course, in terms of training objectives, emergency language service volunteers are now the main force of the national emergency language service. The recruitment, training, use and evaluation of the emergency language workforce can help to improve the competence of the emergency language service (Teng, 2021). Therefore an in-depth discussion on the competence indicator’s of the emergency language service personnel was possible to propose the evaluation criteria of the emergency language service personnel and the specific content of the emergency language competence (Li & Pan, 2021).

Cai (2020) pointed out that emergency language can only produce qualified emergency language service reservists if emergency language teaching was carried out in relevant fields in language teaching. Therefore, the inclusion of situational pedagogy in emergency language curriculum was considered an effective method of teaching foreign languages (Jones et al., 2013). So far, emergency language research is an emerging field, from the related literature, most of the concerns are focused on the necessity of emergency language services for public emergencies, mechanism construction, strategy analysis and other macro-level, for emergency language education and training of emergency language personnel is slightly involved in the content of emergency language education and training of emergency language personnel, but the design for emergency language curriculum is only at the recommendation stage, and there is little research on specific course design (Chen, 2021). In addition, in undergraduate education, situational teaching was more often used in mathematics, fine arts, and biology courses, but none of the existing foreign language teaching was also interspersed with teaching content such as emergencies and language, or typical scenarios and language (Cai, 2020). Emergency language service is mainly for the emergencies, with the suddenness of time and the complexity of the environment, so the emergency language teaching means that the students have relatively limited opportunities to complete the learning in the real environment. The “emergency language service classroom theory + practice teaching” model is a teaching training carried out by teachers in simulated situations and under pre-determined conditions, which is applicable to the application of contextual teaching methods and cultivate emergency language talents.

Theoretical framework

Brown et al. (1989) were the first to propose a definition of situational teaching and learning, argued that knowledge learning was best carried out in context, learning independently of context was meaningless, so students should be involved in activities in different disciplines in order to solve the problem of inert, decontextualised knowledge that students are unable to promote to the real world. Lave and Wenger (1991) proposed a “theory of situational teaching and learning”, which elaborated on situational teaching and learning, argued that learning consisted of a combination of learning agents, activities and the world, and that the social aspects of learning were easily overlooked, suggested that learning usually took place in the context of activities that involved problems or tasks, other people, a particular environment or cultures. The learning environment provided a framework for specific learning activities to guide and support learners. Contu and Willmott (2003) critically analyze the coherence, acceptance and diffusion of “situated learning theory”, argued that the theory departed from the accepted body of knowledge on organisational learning, suggested that learning should be achieved using community practices, that learning embedded in social and physical environments was more effective than non-situated learning. situated learning. Furthermore, they described learning as the process of organising behaviour through individually learned cognitive activities, suggested that collective action embedded in organisational culture can be knowledge-acquiring and challenging.

In the specific teaching and learning process, teachers often used the activities and tools of contextualisation, that was artificially simulating real social environments in the classroom and mimicking the context followed by instructional design to enable learners to acquire knowledge by embedding the themes into their ongoing experiences and allowing them to live the themes in the context of real-world challenges (Binti Pengiran & Besar, 2018). Therefore, situational teaching required teachers to combine teaching content with experiential learning activities (Ajani, 2023), and second language acquisition required a more realistic environment, but most learners were not in a position to be in such an environment, which the reason why required teachers to artificially create an environment for second language learning and communication (Zhang et al., 2018).

Emergency languages are Chinese, foreign languages, ethnic languages, dialects, sign languages and so on, used for rescue and relief operations or crisis communication during sudden-onset natural disasters, accidents and catastrophes, public health incidents, and social security incidents (Cai, 2020; Wang et al., 2020b). Given that emergency language services are geared towards the generation of emergencies, the suddenness of time and the complexity of the environment dictate that the opportunities for students in an emergency language course to be able to complete their learning in an authentic environment are relatively limited. So it is the pedagogical training carried out by the teacher in controlled environments and pre-determined conditions while simulating emergency situations that can make up for the objective limitations of the conditions to a certain extent (Li & Pan, 2021). Therefore, in this study, based on the classification of “emergencies” in the Emergency Response Law of the People’s Republic of China issued by the China National People’s Congress (2007), emergencies are classified into natural disasters, accidents and calamities, public health incidents and social security incidents in four situational teaching units. Teachers are required to determine the main language teaching of English in emergency situations in order to help students master emergency language knowledge and develop emergency language skills.

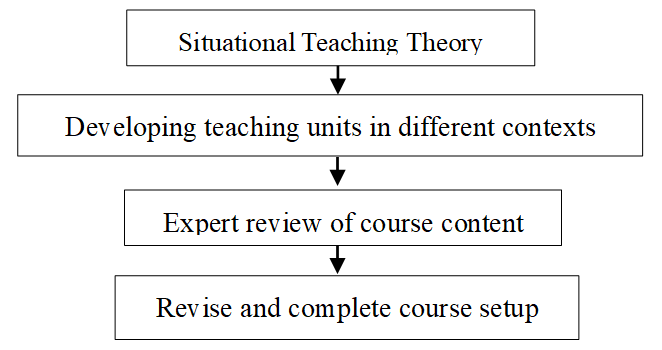

Figure 1. Research framework for emergency language courses in context

As shown in figure 1, in the process of curriculum construction, due to the special nature of the emergency language course that the context cannot be truly recovered, this study adopts the situational teaching method for curriculum design, which is based on the classification of “emergencies” by China National People’s Congress (2007): natural disasters, accidental disasters, public health events and social security events, the study designed 4 situational teaching units, then constructed the course content from the teaching objectives, course units, teaching methods and activities, finally established the final draft of the teaching content through expert review.

METHOD

This study adopts the situational teaching method for curriculum design, based on which the four units of emergency situation design are used to prepare the first draft of the curriculum, and the content validity of the curriculum construct is reviewed by the experts, so as to form the competence index of emergency language talents and the emergency language curriculum oriented by situational simulation.

Experts’ Validity of the Course Objectives

Li & Pan (2020) suggested that the indicators for cultivating emergency language talents at the undergraduate level of universities contained the following elements: solid language application skills, good intercultural communication skills, relevant professional knowledge and professionalism. Accordingly, the curriculum construction of the emergency language talent cultivation system mainly focuses on the following 3 aspects: solid language skills, excellent cross-cultural communication skills and complete emergency professional knowledge. Taking into account the actual situation of undergraduate training for Chinese university students, this study positions the competence indicators of emergency language courses into 3 modules: emergency language application competence, emergency professional knowledge competence and emergency language communication competence.

Emergency Language Application Competence

Language application competence is at the core of emergency language services (O’ Brien & Federici, 2020), the emergency language application competence mainly refers to the comprehensive ability to use the emergency language in an emergency situation (Wang & Liu, 2022). Therefore, in order to cope with the risk of disasters caused by multilingual barriers, more b/multilingual speakers should be trained, multilingualism should be taught in the educational process and multidirectional communication programmes should be developed (Uekusa & Mattewman, 2023). It is also widely recognised by disaster researchers that although the best disaster management and recovery practices are inclusive, they are still dominated by English in academia (Hua & Li, 2021). Based on the dominance of English as the language of disaster and the national context of China, this course deals with the language of emergency response focusing mainly on Chinese and English communication and application skills.

Emergency Professional Knowledge Competence

Multilingual education is both an inter-linguistic discipline and belongs to an intercultural cross-discipline (Uekusa & Mattewman, 2023). In the prevention and control of this new coronary pneumonia outbreak, volunteers from language majors had little knowledge of the medical field and had to turn to professionals on the spot for emergency response (Teng, 2020; Zheng, 2020). Therefore, the work of emergency language services belongs to the professional field service, which needs the composite talents of “language + profession” (Bourrier, 2018). As an inter-professional discipline, in order to cultivate composite talents to meet the needs of complex emergency situations, emergency language personnel should be trained to master the professional knowledge of the relevant service areas, to use the working language and language technology.

Emergency Language Communication Competence

Research on disaster language and communication suggested that research related to verbal communication and how it occurs after a disaster was critical (McKee, 2014). Culture and language are also inseparable, and a mixture of language knowledge and culture is the focus of language teaching and learning (North & Piccardo, 2016). So it has always been the case that cultural factors, as indicators of competence developed by students, should also be attached to the teaching of the four skills of language teaching: listening, speaking, reading, and writing (Kramsch, 2013). Good intercultural communicative competence can help develop emergency language service providers’ sense of inclusion, help them adapt to and resolve conflicts that may be brought about by multiculturalism more quickly, reduce communicative biases or misunderstandings, which maximise the satisfaction of communication needs of all parties (Hunt et al., 2019). Therefore, the development of students’ emergency language communicative competence, including emergency professionalism and intercultural communicative competence is necessary in emergency language courses.

Experts’ Validity of the Curriculum Content

The curriculum content was selected by means of a purposive sampling of a sample of experts, and content validity was assessed by 5 experts, from pedagogy, emergency management training, foreign language teaching professions and emergency service teams. Their personal details are provided in table 1.

|

Table 1. Experts Invited to Validate the Emergency Language Curriculum |

||||||

|

Expert |

Gender |

Education |

Profession |

Professional title |

Teaching age |

Work unit |

|

1 |

Male |

Doctor |

Education |

Professor |

35 |

University |

|

2 |

Female |

Master |

Curriculum |

Associate Professor |

15 |

University |

|

3 |

Male |

Master |

Manage |

Professor |

20 |

University |

|

4 |

Male |

Doctor |

Education manage |

Associate Professor |

15 |

University |

|

5 |

Male |

Scholar |

Rescue |

- |

10 |

Rescue team |

After the feedback from the 5 experts, the study followed the 5 experts’ opinions and refined the task “Advice on going out during an epidemic as a community service worker” in the second lesson of “Public Health Emergencies” in Unit 1 to “People who go out” in order to make it more relevant to the actual situation and bring more thoughts to the students. Refinement of the term “people who go out” and thus the contextual situation is more in line with the actual situation, that can provide students with more food for thought.

In the Unit 2 “Emergency Natural Disasters”, the second lesson “Emergency Service Providers Provide Emergency Filing for Floods” consider that the introduction of the scenario is followed by a written assignment to the group that requires the students to work on the scenario in a collaborative learning format; In addition, sudden natural disasters including other severe weather conditions such as hurricanes, blizzards, lightning, mudslides, and other weather can be provided to students outside of the classroom for contextual expansion, which can help students learn more about natural disaster terminology, the conditions in which they occur, and emergency preparedness.

The course on “Terrorist Attacks” in Unit 3 “Social Security Emergencies”, has fewer real-life scenarios that are difficult to resonate with students and put them into context. So it should be introduced over a longer period of time, using a video or other means of contextual introduction.

In Unit 4 “Sudden Accident Disaster”, the second lesson suggests modifying the “aircraft crash emergency rescue” part, because the aircraft crash survival rate is low, the real situation is relatively small. So the emergency services in the aircraft crash is more in the face of the families of the passengers, which can be changed to “appease the family members of passengers in an aircraft crash as an airport staff member”, so that the situation is more realistic, and can also test the emergency professionalism and communication skills.

The teaching contents were modified and improved based on the revised opinions of experts. The teaching units was refined after the experts’ revisions were consolidated, culminating in a formal lesson plan for the 4 units of the emergency language course. All the experts agreed that the 8 selected disaster situation were common, the teaching objectives were well-designed, the setting of the situational tasks was close to the teaching objectives, the disaster situation was integrated into the typical tasks of the curriculum of emergency language, college students’ emergency language ability had improved, knowledge transfer and training ability had been achieved, and moral cultivation had been realized.

RESULTS

Objectives of Emergency Language Curriculum

As shown in table 2, this study divides the talent training objectives into the above three modules, i.e., 3 first-level talent competency modules, and each module is subdivided into 10 second-level talent competency indicators.

|

Table 2. Emergency Language Talent Capability Index System |

|

|

Talent competency modules |

Talent competency indicators |

|

A. Emergency Language Application Competence |

A1. Ability to apply English language fluency in critical situations. |

|

A2. Ability to apply Chinese language fluency in critical situations. |

|

|

A3. Ability to interpret proficiently in English in critical situations. |

|

|

A4. Ability to translate in English in critical situations. |

|

|

B. Emergency Professional Knowledge Competence |

B1. Ability to source, process and share information in crisis situations |

|

B2. Ability to acquire basic knowledge of first aid and protection, and to maintain good psychological quality and resilience in crisis situations. |

|

|

B3. Ability to be familiar with relevant national policies and legal knowledge |

|

|

C. Emergency Language Communication Competence |

C1. Ability to maintain a sense of perspective, service and responsibility in emergency response processes. |

|

C2. Ability to work as a team, integration and interpersonal skills in dealing with crisis events. |

|

|

C3. Ability to familiarise oneself with the knowledge of local customs and culture. |

|

Context-simulation-orientated Emergency Language Curriculum

In tasks that do not reflect real-life activities have a negative impact on the development of students’ language knowledge (Ozverir & Herrington, 2011). In contextual pedagogy, setting situations include real scenarios or scenarios that help students to imagine, or teachers use real things to simulate scenarios (Binti Pengiran & Besar, 2018). In the language teaching classroom, students who are subjects of contextual pedagogy perceive that participation in multilingual tasks enables them to identify communication barriers resulting from language use related to culture, interlocutor, situation and context and to develop intercultural communication (Galante, 2022). In conclusion, based on the cultivation of students’ language application ability, language knowledge ability and language communication ability, it is divided into 4 units and 8 contextual tasks according to the emergency situation, in order to realise the cultivation of 10 competence indicators for students’ emergency language service talents.

Unit Content

The unit design model allows for linking knowledge within a discipline, identifying appropriate assessment methods as well as planning relevant teaching and learning processes to develop students’ problem solving skills in authentic contexts (Bowen, 2017). Therefore, this study divides emergency language emergencies into 4 situational teaching units: sudden natural disasters, sudden accidental disasters, sudden public health emergencies, and sudden social security emergencies, then constructs an emergency language curriculum based on the theory of contextual pedagogy.

In Unit 1, public health emergencies are simulated by videos and verbal descriptions. After the teacher teaches words, phrases and sentence patterns related to public health emergencies, general medical knowledge, national policies and emergency treatment, two tasks are designed: informing international students in China about home quarantine and informing expatriates about precautions to be taken when going out during epidemics. Then students are asked to demonstrate in the classroom through role-playing and group discussion.

In Unit 2, a virtual laboratory is used to simulate sudden natural disaster situations. After the teacher teaches the words, phrases and sentence patterns of sudden natural disaster situations, the consequences of sudden natural disasters, precautions to be taken, and general knowledge of risk avoidance, two situational tasks are designed: earthquake rescue and flood emergency publicity. Then the students are asked to complete the teaching and learning activities in the classroom by means of group discussion and role-playing.

In Unit 3, the web video is used to experience sudden social security situations for students. After the teacher teaches the words, phrases and sentence patterns of sudden social security situations, the consequences of sudden social security disasters, precautions to be taken, and general knowledge of risk avoidance, two situational tasks are designed: discussing the precautions to be taken for refugee incursions at the border and organising the activities of pacifying blocked crowds after a terrorist incident. Then students can complete the teaching activities by group discussion and role-playing in the classroom.

In Unit 4, experiencing sudden accident situations with videos and pictures, after the teacher teaches words, phrases and sentence patterns of sudden accident situations, disaster psychology, and disaster communication skills, two situational tasks are designed: rescuing from traffic accidents and reassuring relatives after a plane crash. Then the students complete the teaching and learning activities in the classroom in a role-playing manner.

In the 4 units content design, the teaching objectives, teaching content, teaching time, teaching methods, teaching activities and teaching evaluation methods are shown in table 3.

|

Table 3. Contextual Approaches to Emergency Language Curriculum Development |

||||||

|

Teaching unit |

Teaching object |

Teaching content |

Lesson time |

Teaching method |

Teaching activities |

Assessments |

|

Public health emergency |

A1, A2, A3, A4, B2, B3, C1, C2. |

Words, phrases, and sentence patterns for public health emergencies; medical knowledge, national policy, and emergency treatment. |

8 |

Simulated learning: videos, verbal descriptions of simulated situations |

Role play, group discussion |

Teacher evaluation, group mutual evaluation |

|

Sudden natural disasters |

A1, A2, A3, A4, B1, B2, B3, C1, C2, C3. |

Words, phrases, and sentence patterns for sudden natural disaster situations; sudden natural disaster consequences, precautions, and common sense evacuation. |

8 |

Simulated learning: virtual laboratory simulation scenarios |

Group discussion, role play, |

Teacher evaluation, group mutual evaluation |

|

Social security emergency |

A1, A2, A3, A4, B1, B2, B3, C1, C2. |

Words, phrases and sentence patterns for social security emergencies; national emergency policies for related events and emergency communication skills. |

8 |

Experiential Learning: Webcam Experiential Context |

Role play, group discussion |

Teacher evaluation, group mutual evaluation |

|

Emergency incident |

A1, A2, A3, B2, B3, C1, C2. |

Words, phrases and sentence patterns related to emergencies; disaster psychology, communication skills. |

8 |

Experiential learning: videos, pictures to experience situations |

Role play |

Teacher evaluation, group mutual evaluation |

Instructional Methods

Contextual pedagogy can help learners to easily extract knowledge and apply it when needed in the context of tasks that reflect real-life and present the teaching and learning process (Chiou, 2020). Contextual pedagogy using group learning, role-playing, and case studies as teaching strategies is effective in developing the competence of Chinese university students (Yang & Chen, 2022). Therefore, in the process of constructing emergency language courses under the theory of situational teaching, simulating or experiencing emergency situations and allowing students to complete teaching activities through group cooperation or role-playing can achieve the target of emergency personnel competence.

Assessments

Currently, there is a lack of research in disaster education evaluation in academia and little technical guidance on designing disaster education curriculum and curriculum evaluation (Dufty, 2018). In the midst of the emerging emergency language curriculum design, this study will use a multifaceted approach to the assessment process, including teacher evaluation and group mutual evaluation, in order to increase the credibility of the teaching and learning assessment results. In conjunction with the Emergency Language Course Competency Indicators and the classroom objectives, the teacher provides formative assessment feedback and final evaluation scores based on the completion of situational tasks, including the students’ use of the emergency language, their mastery of emergency knowledge and their use of the emergency language to communicate. Successive groups of students were allowed to evaluate each other, culminating in a final evaluation score for the group, based on 50 per cent teacher ratings and 50 per cent group ratings. This is the more common form of second language assessment, which generally requires ratings to be derived directly from learners’ oral presentations (Ericsson & Simon, 1993).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used the theory of contextual teaching (Lave & Wenger, 1991) to design four contextual teaching units based on the classification of “emergencies” in the Emergency Response Law of the People’s Republic of China issued by the National People’s Congress (2007), and designed the teaching activities and tasks in the units in accordance with the characteristics of the contextual teaching method, such as authenticity, communicativeness, and interestingness. The teaching activities and tasks in the units were designed according to the characteristics of the authenticity, communicative and interesting strategies of the contextual teaching method (Ozverir & Herrington,2011; Wilhelm, 2018).

In contextual pedagogy, learners must infer and acquire knowledge based on contextual information, learners demonstrate how the knowledge they acquire can be used to deal with real-life problems (Lai & Hwang, 2014). The use of contextual pedagogy’s group learning, role-playing and case studies as instructional strategies is effective in developing the competencies of Chinese university students (Yang & Chen, 2022). In this study, questioning, visual presentation or experiential methods (Kim & Hannafin, 2011) were used to introduce the context, and the more appropriate way of introducing the context for adults is not only in line with the laws of second language acquisition for adults, but also helps students to feel the effects of the context first-hand and increase their mastery of the language knowledge, which in turn promotes the effects of reformed learning and teaching experience (Parmaxi, 2023). Therefore, situational tasks are relevant to the situation that elicit students’ assumptions and reflections on real-life problems in an emergency situation (Chiou, 2020) are more likely to lead to the acquisition of target language knowledge in a real-life context (Ozverir & Herrington, 2011), which is in line with the characteristics of an emergency language curriculum. .

Given that emergency language services are aimed at the generation of emergencies, the suddenness of time and the complexity of the environment determine that students in emergency language courses have relatively limited opportunities to complete their learning in a real environment. The “theory + practice teaching in emergency language service classroom” mode is a teaching training carried out by teachers in simulated situations under controlled environments and predefined conditions, which can compensate for the objective limitations to a certain extent, and it is also a bold attempt to broaden the teaching channels (Li & Pan, 2021).

During the implementation of contextual pedagogy, teachers can provide different realistic situational settings for teaching and learning in the emergency language classroom. In the instructional design of a contextual emergency language course, teachers organise teaching and learning activities and provide students with the opportunity to practise inquiry, cooperation and autonomy. In addition, teachers are also required to control the process and duration of the contextual simulation activities and ultimately evaluate the simulation of the various roles (Gao & Chen, 2023). The above teaching and learning activities provide a suitable platform for the implementation of the curriculum, and at the same time, as an important part of the curriculum, they are constantly practised by the students, which will contribute to the cultivation of emergency language talents, and promote the mastery of language skills as well as the practical use of the language by the students.

Specifically in the field of emergency language, the emergency language competence indicator is the emergency language knowledge and competence needed to cope with emergencies (Li et al., 2020). At present, the research on the main body of emergency language service talents is still rare, the research on the competence indicator of emergency language service talents from the perspective of the competence of emergency language service volunteers is even more scarce (Teng, 2021). Tan (2023) suggested that disaster education emphasized not only the teaching of knowledge and skills, but also the instruction of emotions and values primarily to develop students’ sense of global citizenship and responsibility, to promote their intercultural understanding and communication. According to Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2016, pp. 3-4), “competence” refers not only to “knowledge and skills”, but also to “the sum of the abilities to organise knowledge, social resources to meet the demands of complex tasks in a given context, and social resources to fulfil complex tasks in specific contexts”. This study locates the competence indicators of emergency language courses into three major modules: emergency language application competence, emergency professional knowledge competence and emergency language communication competence, and finally divides the talent cultivation objectives of emergency language courses into the above three modules, i.e., 3 first-level talent competence modules, and at the same time subdivides each module into 10 second-level talent competence indicators. Studying the competence indicators of emergency language service talents is also the focus of research on the cultivation of emergency language service talents and emergency language courses (Li, 2020). Therefore, establishing the competence indicators for the training of emergency language talents is of great and urgent significance for improving the comprehensive quality of emergency language talents and promoting teachers’ thinking about disaster teaching (Tan, 2023).

Limitation

At present, China’s attention and development of disaster education is relatively lagging behind and there are many problems and shortcomings. At present, many discussions on emergency language are conducted from a macro perspective, the number of micro studies and designs is very small. This study also analyses only from the curriculum design and talent competence indicators, which does not use experimental teaching and other methods to conduct empirical research.

CONCLUSION

In this study, 4 situational teaching units were designed according to the emergencies of emergency language: natural disasters, accidental disasters, public health events and social security events. The curriculum was constructed to contain the teaching objectives, curriculum units, teaching methods and activities, and then reviewed by experts to finalise the final draft of the teaching content. In this study, the learning of the emergency language course is regarded as a contextual practice, and each thematic unit in the design of the emergency language course is set up in a context, which guides the students to learn the language in the environment, to complete the problems raised by the teacher through group collaboration, cooperative discussion and other learning modes, then present the results of the group to reflect on the process of mutual evaluation by the teacher and the group, so as to master the language of emergency and the related professional knowledge to cultivate the quality and ethics of emergency response. In terms of the design of the emergency language curriculum, each learning unit will include three steps, namely, creating a situation, introducing a situation and deepening a situation, and different questions and different tasks will be set up in the classroom according to the different situations in which various types of emergencies occur, so that students will be repeatedly given communicative language training that the integration of language skills and disciplinary knowledge into communication literacy will be realised. Students who were the target of contextual pedagogy in the language teaching classroom also perceived that after engaging in language tasks, they were able to identify communication barriers resulting from culturally, interlocutor, situation and context-related language use, an important skill for intercultural communication development (Galante, 2022) in order to enhance the three major modules of the emergency language talent indicator, which include emergency language application, knowledge, and communication skills. In this study, the creative design of the emergency language curriculum has innovative value. Teachers carry out teaching training in simulated situations, to a certain extent, to make up for the objective limitations of the real situation of emergency language, but also a bold attempt to broaden the teaching channels, which helps to train students’ emergency language skills.

In conclusion, disaster education is an important and urgent education, which is of great significance for cultivating emergency language talents, improving the emergency language ability of college students, and then enhancing the national emergency response capability. The research on disaster education in China is still insufficiently detailed and requires continuous thinking, practice and innovation in teaching methods. Although this study explored the contextual pedagogy of emergency language courses, it still failed to measure the effectiveness of emergency language courses under the contextual pedagogy, and the next step should be an in-depth discussion of the nature of emergency language courses, and further exploration of the connotation of the discipline of international language services and talent cultivation mode under the background of “new liberal arts”.

REFERENCES

1. Ajani, O. The role of experiential learning in teachers’ professional development for enhanced classroom practices. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 12(4), pp. 143-155. https://doi.org/10.5430/jct.v12n4p143

2. Binti Pengiran, P. H. S. N., & Besar, H. Situated learning theory: The key to effective classroom teaching? HONAI, 1(1), pp. 49-60. https://www.journals.mindamas.com/index.php/honai/article/view/1022

3. Bourrier, M. Risk communication 101: A few benchmarks. In C. Bieder & M. Bourrier (Eds.), Risk communication for the future (pp. 13-26). Springer.

4. Bowen, R. S. The benefits of using backward design. Understanding by design (pp. 11-43). Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching.

5. Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), pp. 32-42. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X018001032

6. Cai, J. G. Exploration on emergency language services and emergency language teaching. Journal of Beijing International Studies University, 42(03), pp. 13-21. https://doi.org/10.12002/j.bisu.280

7. Chen, L. W. Analysis of demand for emergency language services in China based on hierarchy of needs theory. Language Policy and Planning Research, 1(02), pp. 28-39. https://www.bfsujournals.com/c/2021-11-03/509478.shtml

8. Chiou, H. H. The impact of situated learning activities on technology university students’ learning outcome. Education + Training, 63(3), pp. 440-452. http://doi.org/10.1108/ET-04-2018-0092

9. Contu, A., & Willmott. H. C. Re-embedding situatedness: The importance of power relations in situated learning theory. Organization Science, 14(3), pp. 283-297. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.14.3.283.15167

10. Dewi, P. Y. A., & Primayana, K. H. Effect of learning module with setting contextual teaching and learning to increase the understanding of concepts. International Journal of Education and Learning, 1(1), pp. 19-26. https://doi.org/10.31763/IJELE.V1I1.26

11. Dufty, N. A new approach to disaster education. In The International Emergency Management Society Annual Conference, November 13-16, Manila, Philippines. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329105392_A_new_approach_to_disaster_education

12. Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. Methods for protocol analysis. In K. A. Ericsson & H. A. Simon (Eds.), Protocol analysis: Verbal reports as data (pp. 223-286). The MIT Press.

13. Feldhege, J., Moessner, M., Wolf, M., & Bauer, S. Changes in language style and topics in an online eating disorder community at the beginning of the covid-19 pandemic: Observational study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(7), Article e28346. https://doi.org/10.2196/28346

14. Galante, A. Affordances of plurilingual instruction in higher education: A mixed methods study with a quasi-experiment in an English language program. Applied Linguistics, 43(2), pp. 316-339. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amab044

15. Gao, X. H., & Chen, P. F. Establishment of a geriatric nursing curriculum with human caring by situational simulation. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 13(1), pp. 71-82. https://doi.org/10.5430/jct.v13n1p71

16. Hua, Y. P., & Li, J. Ability test of emergency language translation. Journal of Tianjin International Studies University, 28(04), pp. 43-50. https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=1k0f08y0ub0j04m0376h0et0mv670674&site=xueshu_se&hitarticle=1

17. Hunt, M., O’Brien, S., Cadwell, P., & O’Mathúna, D. P. Ethics at the intersection of crisis translation and humanitarian innovation. Journal of Humanitarian Affairs, 1(3), pp. 23-32. https://doi.org/10.7227/JHA.022

18. Jones, S., Myhill, D., & Bailey, T. Grammar for writing? An investigation of the effects of contextualised grammar teaching on students’ writing. Reading and Writing, 26, pp. 1241-1263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-012-9416-1

19. Kim, H., & Hannafin, M. J. Developing situated knowledge about teaching with technology via web-enhanced case-based activity. Computers & Education, 57(1), pp. 1378-1388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.01.008

20. Kramsch, C. Culture in foreign language teaching. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 1(1), pp. 57-78. https://doi.org/10.1590/2176-457333606

21. Lave, J., & Wenger, E. Structuring resources for learning in practice. In J. Lave & E. Wenger (Eds.), Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation (pp. 91-100). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355

22. Lai, C. L., & Hwang, G. J. Effects of mobile learning time on students’ conception of collaboration, communication, complex problem-solving, meta-cognitive awareness and creativity. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation, 8(3-4), pp. 276-291. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMLO.2014.067029

23. Li, Y., Rao, G., Zhang, J., & Li, J. Conceptualizing national emergency language competence. Multilingua, 39(5), pp. 617-623. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2020-0111

24. Li, Y. M. Pay attention to language emergency issues in public emergencies. Language Strategy Research, 5(02), pp. 1-3. http://yyzlyj.cp.com.cn/CN/abstract/abstract298.shtml

25. Li, Y. M. Educational issues in preface emergency language services. Language Service Research, 1(00), pp. 8-13.

26. Li, Y. Y., & Pan, X. T. Research on the construction of emergency language service talent training system. Journal of Tianjin International Studies University, 28(4), pp. 10-19. https://www.doc88.com/p-91661766743209.html

27. Liu, D., & Lei, L. Technical vocabulary. In S. Webb (Ed.), The routledge handbook of vocabulary studies (pp. 111-124). Routledge.

28. McKee, R. Breaking news: Sign language interpreters on television during natural disasters. Interpreting, 16(1), pp. 107-130. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.16.1.06kee

29. North, B., & Piccardo, E. Developing illustrative descriptors of aspects of mediation for the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR): A Council of Europe project. Language Teaching, 49(3), pp. 455-459. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444816000100

30. O’Brien, S. Translation technology and disaster management. In J. D. Cintas & S. Massidds (Eds.), The routledge handbook of translation and technology (2nd ed., pp. 720-725). Elsevier.

31. O’Brien, S., & Federici, F. M. Crisis translation: Considering language needs in multilingual disaster settings. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 29(2), pp. 129-143. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-11-2018-0373

32. O’Brien, S., Federici, F., Cadwell. P., Marlowe, J., & Gerber, B. Language translation during disaster: A comparative analysis of five national approaches. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 31, pp. 627-636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.07.006

33. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. E2030 Conceptual Framework: Key Competencies for 2030. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030-CONCEPTUAL-FRAMEWORK-KEY-COMPETENCIES-FOR-2030.pdf

34. Ozverir, I., & Herrington, J. Authentic activities in language learning: Bringing real world relevance to classroom activities. In EdMedia+Innovate learning (pp. 1423-1428). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education.

35. Parmaxi, A. Virtual reality in language learning: A systematic review and implications for research and practice. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(1), pp. 172-184. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1765392

36. Ramadhan, S., Sukma, E., & Indriyani, V. Environmental education and disaster mitigation through language learning. Earth and Environmental Science, 314(1), Article e012054. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/314/1/012054

37. Shen, Q. Directions in language planning from the COVID-19 pandemic. Multilingua, 39(5), pp. 625-629. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2020-0133

38. Tan, F. F. Review and Prospect of Disaster Education Research in China. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Educational Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries, August 7, Oxford, UK. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374999729_Review_and_Prospect_of_Disaster_Education_Research_in_China

39. Teng, Y. J. Emergency language services: Research topics and research paradigms. Journal of Beijing International Studies University, 42(1), pp. 31-44. https://doi.org/10.12002/j.bisu.268

40. Teng, Y. J. Competency of emergency language service providers and evaluation of emergency language talents. Journal of Tianjin International Studies University, 28(04), pp. 20-31+157-158. https://journal.bisu.edu.cn/article/2020/1003-6539/1003-6539-42-1-21.shtml

41. The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. Law of the People’s Republic of China on Emergency Response. http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/c198/200708/91cd75de0e74484bb912f9b6c96af839.shtml

42. Uekusa, S. Disaster linguicism: Linguistic minorities in disasters. Language in Society, 48(3), pp. 353-375. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404519000150

43. Uekusa, S., & Matthewman, S. Preparing multilingual disaster communication for the crises of tomorrow: A conceptual discussion. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 87, Article e103589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103589

44. Wang, L. F., & Liu, H. P. “New Liberal Arts” International Language Service discipline connotation and training model. China ESP Research, 2022(03), pp. 1-9. http://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=7108556084

45. Wang, L. F., Mu, L., Liao, R. X., ... & Cui, Q. L. Multi-dimensional thinking on emergency language service response and talent preparation in the global fight against the epidemic. Contemporary Foreign Language Studies, 1(4), pp. 46-54. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-8921.2020.04.005

46. Wang, L. F., Ren, J., Sun, J. W., & Meng, Y. Y. The concept, research status and mechanism construction of emergency language services. Journal of Beijing International Studies University, 42(01), pp. 21-30. https://doi.org/10.12002/j.bisu.261

47. Xiong, Y., Meng, W., & Li, H. Ruminating on the Construction of a Corpus of Talents for Emergency Language Services in China. In The 2nd International Conference on Humanities, Wisdom Education and Service Management, July 19, Online. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2-38476-068-8_18

48. Yang, X., & Chen, P. Applying active learning strategies to develop the professional teaching competency of Chinese college student teachers in the context of geography education. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 21(7), pp. 178-196. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.21.7.10

49. Zhang, J., Beckmann, N., & Beckmann, J. F. To talk or not to talk: A review of situational antecedents of willingness to communicate in the second language classroom. System, 72, pp. 226-239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.01.003

50. Zheng, Y. Mobilizing foreign language students for multilingual crisis translation in Shanghai. Multilingua, 39(5), pp. 587-595. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2020-0095

FINANCING

The authors did not receive financing for the development of this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: An Zhu.

Methodology: Peng-Fei Chen.

Investigation: An Zhu, Peng-Fei Chen.

Data Curation: Peng-Fei Chen.

Writing - Original Draft: An Zhu.

Writing - Review & Editing: Peng-Fei Chen.

Supervision: Peng-Fei Chen.