Category: Finance, Business, Management, Economics and Accounting

ORIGINAL

From a wealth management career to employee career success satisfaction: exploring the mediating role of job competency

De la carrera de gestión de patrimonios a la satisfacción con el éxito profesional de los empleados: exploración del papel mediador de la competencia laboral

Benil Dani Alexander1 ![]() *, S. Vasantha1

*, S. Vasantha1 ![]() *, M. Thaiyalnayaki1

*, M. Thaiyalnayaki1 ![]() *

*

1School of Management Studies, Vels Institute of Science, Technology and Advanced Studies, (VISTAS), Chennai, India.

2Department of MBA, Saveetha Engineering College, Tamil Nadu, India.

3School of Management Studies, Vels Institute of Science, Technology and Advanced Studies (VISTAS), Chennai, India.

Cite as: Alexander BD, Vasantha S, Thaiyalnayaki M. From a wealth management career to employee career success satisfaction: exploring the mediating role of job competency. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2024; 3:903. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2024903

Submitted: 06-02-2024 Revised: 25-04-2024 Accepted: 10-06-2024 Published: 11-06-2024

Editor: Dr.

William Castillo-González ![]()

ABSTRACT

In this current study, our main goal is to explore the connections between wealth career management, job competency, and satisfaction with career success. Moreover, it seeks to explore the intermediary mechanisms through which wealth career management affects employees’ level of contentment with their professional trajectories. Employing the analytical tool of structural equation modelling (SEM), the study has yielded noteworthy insights. SEM analysis findings underscore the pivotal role of job competency as a mediator. In essence, job competency serves as an explanatory link, shedding light on how different facets of wealth career management - namely, career development, superior work performance, intention to stay and performance management- influence an individual’s career success satisfaction. This suggests that the way in which employees perceive their own competence within their careers significantly influences how the different aspects of wealth career management affect their satisfaction with career success.

Keywords: Wealth Management; Competency; Job Competency; Career Success Satisfaction; Superior Work Performance; Intention to Stay; Performance Management.

RESUMEN

En el presente estudio, nuestro principal objetivo es explorar las conexiones entre la gestión de la carrera patrimonial, la competencia laboral y la satisfacción con el éxito profesional. Además, pretende explorar los mecanismos intermediarios a través de los cuales la gestión patrimonial de la carrera influye en el nivel de satisfacción de los empleados con sus trayectorias profesionales. Utilizando la herramienta analítica de la modelización de ecuaciones estructurales (SEM), el estudio ha arrojado resultados dignos de mención. Los resultados del análisis SEM subrayan el papel fundamental de la competencia laboral como mediador. Esencialmente, la competencia laboral sirve de vínculo explicativo, arrojando luz sobre cómo influyen las distintas facetas de la gestión de la carrera profesional en función de la riqueza -a saber, el desarrollo profesional, el rendimiento laboral superior, la intención de permanecer y la gestión del rendimiento- en la satisfacción del éxito profesional de un individuo. Esto sugiere que la forma en que los empleados perciben su propia competencia dentro de sus carreras influye de manera significativa en cómo los diferentes aspectos de la gestión de la carrera patrimonial afectan a su satisfacción con el éxito profesional.

Palabras clave: Gestión de Patrimonios; Competencia; Competencia Laboral; Satisfacción con el Éxito Profesional; Rendimiento Laboral Superior; Intención de Permanencia; Gestión del Rendimiento.

INTRODUCTION

In a post-industrial economy, the shifts taking place in the core features of work and the work environment are resulting in fresh mindsets, necessary skills, expertise, and understanding for attaining effectiveness in both employment and job performance. This viewpoint is supported by studies conducted,(47) as well as.(85) In the research,(76) it is suggested that these transformations, driven by factors such as technological advancements, innovative management approaches, and the competitive dynamics of the global marketplace, are prompting policymakers to consider the competencies that will be vital for achieving success in the evolving professional landscape.

Securing fresh talent stands as a pivotal necessity for enterprises on a global scale.(63,37) The challenges posed by tight labour markets in developed nations underscore the need for organizations to effectively allure, inspire, and retain their employees.(18) This becomes especially crucial in contexts where labour markets are fiercely competitive, necessitating global firms to attract and keep skilled employees who contribute value, according to research.(54)

Given that career advancement is an effective approach to retain employees, it holds significance for wealth management firms to implement efficient career administration practices. The career progression aims for incremental advancement by aligning with initiatives to elevate employees’ expertise within their chosen professions.

Skilful navigation of one’s career can have a crucial influence on improving employees’ job proficiency, ultimately resulting in heightened contentment with their career accomplishments. Gaining valuable insights can be achieved by delving into the potential impact of job competence on the relationship between successful management of wealth career and the satisfaction derived from professional achievements.

Literature review

The Perception of Wealth Career Management and Job Competency

The competence of a person in their job is closely linked to various inherent factors within their work sphere. These factors include knowledge, skills, attitudes, traits, motivations, and beliefs. Research conducted,(21,73) as well as,(29) highlights how this combination of factors collectively contributes to effective job performance. According to,(60) knowledge pertains to the reservoir of relevant information necessary for accomplishing a job. Zaim’s(91) defines skill as the mechanism through which individuals are empowered to excel in a particular job and meet their professional obligations. George(38) emphasize that attitudes are crucial in moulding and encapsulating an individual’s emotional and cognitive stance towards their job and the organizations they are affiliated with. These attitudes go on to exert influence over their future interactions and experiences. As per,(90) competencies encompass behavioral dimensions that are directly linked to exceptional job performance.(9)

Enterprises have a crucial role in career management frameworks in today’s business world.(84,44,48) They act as facilitators and developers of their workforce’s potential as highlighted. According,(66,64) organizational career management (OCM) comprises a range of measures, processes, and assistance that companies offer to improve their employees’ professional achievements.(4,5) The influence of OCM on employees’ career paths is highly significant within the wealth management industry. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate career management specifically within the field of wealth management. The focus was on understanding how employees view strategies related to advancing their careers in this context that is centred around wealth. Numerous research studies have explored the field of OCM activities. Numerous researchers, including,(22,41,16,19) have made significant contributions to the field of exploration. Baruch(16) as well as(19) have conducted detailed analyses on OCM practices. A comprehensive compilation of career management practices has been presented(41) which is considered to be one of the most extensive compilations in this area. The ownership of careers within organizations is still retained, and its administration falls under the purview of human resource management (HRM). This point has been emphasized by Campbell along with(25) and also.(41) In the field of human resource management, organizations employ a variety of career strategies methods, activities, programs, and approaches. According to,(17) these diverse practices can effectively guide individuals in their career paths.

Wealth management firms have a strong advantage in effectively carrying out career management tasks for their employees, such as training, mentorship, performance assessment, and developmental initiatives. These initiatives have a positive influence on the enhancement of job competency. For instance, according to the study conducted,(17) performance appraisal provides insights into career planning and enhances employees’ understanding of their performance. Similarly, research(10) emphasizes that mentoring plays a pivotal role in guiding decisions related to career development.

H1. The perceived wealth management careers can potentially yield a positive impact on job competency.

Job Competency and Career Success Satisfaction

In(40) conducted a study that revealed that the satisfaction of career success involves the emotions of individuals that come from different aspects of their careers, including both internal and external factors. These factors comprise elements such as compensation, prospects for progression, and avenues for personal and professional growth. The satisfaction employees perceive in their career success reflects their sentiments regarding their roles, accomplishments, and success within their careers.(39) According to the works of,(77,13,62) career success satisfaction incorporates both external and internal results, making use of both factual and personal measures Objective career success refers to visible indicators that reflect an individual’s position in their career, according to(8) Various research studies, including(82) and the analysis,(50) have shown that specific elements such as salary, promotion opportunities, family circumstances,(68) and job level (as highlighted(49) act as indicators of objective career success. In contrast, subjective achievement in one’s career refers to how fulfilled and satisfied an individual feels with their chosen occupation as researched.(49) This aspect is primarily evaluated through the level of fulfillment individuals experience in their careers. Judge(50,64) align with this perspective on subjective career success. It revolves around an individual’s personal assessment of their accomplishments and overall happiness with the direction of their chosen career path.

Differing from objective career success, which relies on external viewpoints and doesn’t encompass an individual’s self-assessment, The importance of personal success in one’s career has been increasing, as highlighted in the study.(8) This research study places its focus on employees’ satisfaction with their career success satisfaction.

This study has incorporated four distinct aspects of wealth career management: career development, superior work performance, intention to stay, and performance management.

Career development, as defined,(88) pertains to progression within the employee’s current organization. According,(87) there are four main aspects of advancing one’s career. These include achieving career goals, enhancing professional abilities, finding opportunities for growth, and receiving appropriate compensation. As per,(59) critical elements of career growth involve an employee’s environment, interactions, and ability to adapt to change.(46)

The assessment of superior performance can be accomplished through a competency-based Performance Management System (PMS), as outlined.(57,1) Aligning employee competencies with job prerequisites is asserted to enhance both employee and organizational performance, while also resulting in heightened satisfaction.(75) A competency model precisely outlines the skills, knowledge, and traits essential for effectively carrying out a particular role, thus offering a framework for supervisors to engage in feedback discussions focused on key areas.(71)

The concept of “intent to stay” refers to how likely an employee perceives themselves to continue working in their current position, as explained.(58) The role of “intent to stay” in predicting employee retention has been emphasized in numerous studies. Price(67) have both explored this concept. In Ellenbecker’s research conducted,(33) it was found that the most important factor in predicting both “intent to stay” and employee retention is their level of satisfaction with their job.(2) These findings support the conclusions reached by other researchers.(81,4,70) They collectively found a clear connection between satisfaction at work, the desire to remain in the job, and employee retention.(86)

Performance management covers a broad spectrum of tasks, policies, processes, and interventions designed to support employees in improving their performance, as articulated.(31) Conversely, performance measurement involves the process of assessing the level of achievement attained by individuals or organizations in meeting their goals and strategies, as elucidated.(34,51)

H2. Job competency can positively influence career success satisfaction

Perceived wealth career management and career success satisfaction

Implementing successful strategies for managing careers can greatly improve employee satisfaction in wealth management companies. Notably, specific elements of career management, like initiatives focused on job rotation, show a positive correlation with fulfilment in career achievements, as indicated.(26) Furthermore, according to studies conducted,(40,64) the satisfaction derived from professional achievements can also be enhanced by implementing additional strategies like career sponsorship, career development initiatives and training programs.

Studies suggest that companies strive to improve employee contentment with their professional accomplishments by establishing robust support mechanisms, including training, performance evaluation, and engaging tasks.(23,24) These proactive measures create a sense of organizational endorsement among employees, thereby leading to heightened satisfaction with career success and a more pronounced intent to remain with the organization.(20) Drawing from the research conducted,(15,5) the hypothesis can be formulated as follows:

H3. Career satisfaction can be enhanced by the way wealth-related professions are perceived and managed.

Job Competency’s Role as a Mediator

Job competency not only has a direct effect on one’s satisfaction with their career success but it can also serve as a mediator between effective career management and being content with one’s professional achievements. According to,(14,52) a mediator serves as the pathway through which an independent variable influences the dependent variable of interest. Two distinct mediation processes are: complete mediation and partial mediation. In the context of statistical analysis, complete mediation occurs when the relationship between the independent and dependent variables loses its significance upon inclusion of a mediator variable. Conversely, partial mediation occurs when there is a reduction in the strength of the direct effect, but it remains statistically significant even after incorporating the mediator variable.

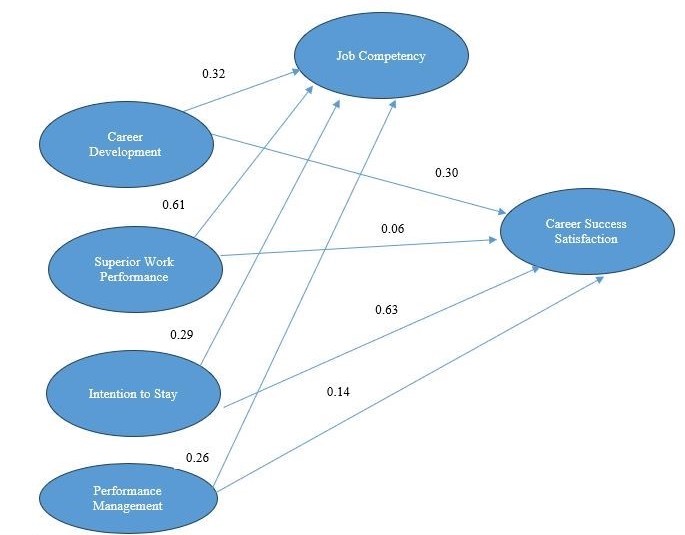

This study explores how organizational support for career development contributes to increased job satisfaction with a specific emphasis on the mediating effect of job competency. Extensive evidence, including studies conducted,(40,26,2,64) support this examination. Proposed conceptual framework shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Proposed conceptual framework

METHOD

To investigate the formulated hypotheses, a questionnaire survey was conducted as part of the data collection process for this study. The assessment of perceived wealth career management utilized a series of 27 items developed.(28) To evaluate job competency, items were selected from the research carried out.(72)

The objects were evaluated using a scale that followed the Likert format with five points. This scale ranged from 1, which represented strong disagreement, to 7, which indicated strong agreement. The data was procured through a survey conducted among wealth managers located in Kerala. The identification of wealth management firms in the city of Kochi, Kerala was carried out. Conclusively, a combined total of 404 surveys were gathered, leading to an achieved response rate of 70 %. After meticulous data screening and refinement, 282 valid surveys were retained for examination, meeting the prerequisites for Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis.(74)

The participants demonstrated a broad spectrum of characteristics, including variations in age, educational background, job title, the field of work, and work experience. Roughly 46 % of the participants were classified as male, whereas 54 % were categorized as female. The prevailing majority of respondents fell within the 21-30 age range and disclosed having less than 5 years of work experience. A notable 64 % possessed a college-level education, with an additional 19 % having pursued post-graduate studies, thereby indicating a highly educated cohort. The largest portion of respondents (44 %) held executive positions within the realm of wealth management.

Building on the research conducted,(49) this study included control variables to maintain its integrity. The variables covered various aspects, such as sex, age, level of education, tenure at the job, and income.

In order to develop accurate measurement models, the study employed both Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) as well as Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The use of EFA was applied to identify sets of variables that could potentially signify a fundamental aspect, while CFA sought to establish the connections between observed measurements and their assumed underlying factors. To ensure easy comprehension and in line with suggestions from Field in 2005 along with researchers Tabachnick and Fidell in 2007, adjustments were made. In order to make it easier to understand the factors that were identified and determine the main elements in the dataset, we chose to begin with EFA using varimax rotation. To ensure that data structure is applicable across populations, cross-validation was carried out. Consistent with Hair et al.’s approach outlined in 2009, both EFA and CFA were performed on a complete dataset for enhanced reliability. In order to carry out a comprehensive examination with accuracy and statistical validity, this investigation utilized structural equation modeling (SEM). This approach allowed for the examination of various relationships among different constructs. By following these outlined methodologies, the research ensures a comprehensive evaluation while upholding strict standards of accuracy.

RESULTS

Individual Measurement Model

EFA and CFA of Perceived Wealth Career Management

The analysis included an examination of 27 components related to managing one’s career and wealth. This investigation resulted in the identification of four distinct aspects: the advancement of one’s career, achieving exceptional job performance, having a desire to remain with the organization, and effective performance management. The findings, as shown in table 1, indicate that these four factors combined account for 67,04 % of the total variability observed. After conducting the Bartlett’s test of sphericity, it was found to be statistically significant. Additionally, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure revealed a sampling adequacy value of 0,957, indicating that the correlation patterns were cohesive and produced reliable factors. These findings align with those reported.(35) The values for the four factors’ Cronbach’s alpha ranged between 0,80 and 0,93, exceeding the suggested minimum reliability threshold of 0,70. Consequently, it can be inferred that the elements within these dimensions demonstrated internal coherence and durability, ultimately establishing a dependable measure.

|

Table 1. Findings from the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) related to perceived wealth career management are summarized below |

||||

|

Item |

Factor |

Eigen-value |

Variance explained (%) |

Reliability alpha (˛) |

|

Factor 1: Advancement of Career |

|

14,27 |

52,88 |

0,92 |

|

CD3: In my job, I possess a thorough comprehension of my abilities. |

0,81 |

|

|

|

|

CD2: I possess a clear understanding of the specific aspects that interest me in my profession. |

0,76 |

|

|

|

|

CD6: My ability to effectively convey my strengths to others in my job is well-developed. |

0,72 |

|

|

|

|

CD1: I have a clear understanding of what is important to me in my career. |

0,69 |

|

|

|

|

CD7: I have a strong ability to discover and pursue progress in my professional domain. |

0,65 |

|

|

|

|

CD4: I possess a solid comprehension of the aspects where I can enhance my performance in my profession. |

0,63 |

|

|

|

|

CD5: I have the ability to reach out to the right people for career advice. |

0,58 |

|

|

|

|

CD8: I possess the ability to identify potential avenues for continued learning and personal development. |

0,56 |

|

|

|

|

Factor 2: superior work performance |

|

1,76 |

6,51 |

0,93 |

|

ITS1: I am confident that my abilities and knowledge are well-suited for the requirements of managing wealth. |

0,65 |

|

|

|

|

SWP12: I believe in the purpose of my company’s mission. |

0,64 |

|

|

|

|

SWP9: Appraising job performance is of utmost importance, and I believe that competency-based performance evaluation plays a vital role in this process. |

0,63 |

|

|

|

|

SWP10: I am of the opinion that utilizing competency-based assessment will help me determine whether I meet the specified performance criteria. |

0,64 |

|

|

|

|

SWP11I have a positive perspective on the responsibilities involved in wealth management. |

0,62 |

|

|

|

|

SWP2: I possess a comprehensive comprehension of the anticipated conduct and actions that are required of me. |

0,60 |

|

|

|

|

CD9: Within the span of one year, I possess a distinct and defined objective for what I aspire to achieve in my professional journey. |

0,58 |

|

|

|

|

SWP13I: feel a strong connection between my objectives and principles, and those of the company I work for. |

0,58 |

|

|

|

|

CD10I have the capacity to set professional objectives for myself that I work hard to accomplish. |

0,55 |

|

|

|

|

Factor 3: intention to stay |

|

1,05 |

3,9 |

0,90 |

|

ITS5: In my company, there are opportunities for employees to progress and move up in their careers. |

0,76 |

|

|

|

|

ITS4: I am satisfied with the working conditions in which I carry out my tasks. |

0,72 |

|

|

|

|

ITS6: In my present position, I am assisted by my supervisors. |

0,71 |

|

|

|

|

ITS7: The lack of stress characterizes my relationship with my managers. |

0,66 |

|

|

|

|

ITS3I find great satisfaction and fulfilment in my work, which brings me a sense of achievement and happiness. |

0,58 |

|

|

|

|

SWP 8: I am confident that the workers in this organization are ready and skilled in handling the obstacles they encounter on a daily basis. |

0,52 |

|

|

|

|

Factor 4: performance management |

|

1,01 |

3,76 |

0,80 |

|

SWP4: I undergo coaching with the goal of improving my performance at work. |

0,71 |

|

|

|

|

SWP7: I have noticed that the employees in my department are quick to accept and adjust to the frequent changes occurring. |

0,70 |

|

|

|

|

ITS2I am satisfied with the salary I receive as it fulfills my financial requirements. |

0,68 |

|

|

|

|

SWP5: I am of the opinion that the overall performance and productivity of every employee within the company are exceptional. |

0,60 |

|

|

|

Afterwards, a test known as Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to evaluate the concept of perceived wealth career management. This notion encompasses four essential elements: career advancement, exceptional job performance, desire to stay with the company, and performance evaluation. The model’s appropriateness was evaluated through an examination of various indices of model fit (χ² = 789,093, df = 315, CFI = 0,91, SRMR = 0,05, RMSEA = 0,07). Based on these indicators, it appears that the model and data are in agreement to a satisfactory extent. When evaluating the accuracy of the measurement model, it is crucial to not only take into account measures of goodness-of-fit but also to identify concrete proof of construct validity.(42)

In order to assess the reliability of wealth career management, our focus was on determining the strength and significance of factor loadings.(79) The results, which can be found in table 2, provide a concise overview of the connections between variables are established through calculations, factor weights that have been standardized, notable ratios (CR), and squared multiple correlations (SMC). According to all the estimated loadings were found to be above 0,5 and statistically significant, with CR values exceeding 1,96. This indicates that the perceived wealth career management concept has satisfactory convergent validity. The results align with the study carried out,(3) as well as the research conducted.(42)

|

Table 2. CFA results of perceived wealth career management |

||||

|

Item |

Estimate |

C.R |

Std. factor loading |

SMC |

|

Factor 1: career development |

|

|

|

|

|

CD3: I have a thorough comprehension of my abilities in my current position. |

1 |

|

0,79 |

0,62 |

|

CD2: I possess a clear comprehension of the aspects I am passionate about in my role. |

0,91 |

13,89 |

0,76 |

0,58 |

|

CD6: I can successfully showcase my abilities to colleagues in my profession. |

0,92 |

15,46 |

0,83 |

0,68 |

|

CD1: I understand the importance of certain aspects in my professional life. |

0,90 |

12,65 |

0,70 |

0,50 |

|

CD7: I possess expertise in discovering progressions within my professional domain. |

0,94 |

15,26 |

0,81 |

0,67 |

|

CD4: I am familiar with the aspects I need to work on in my current role. |

0,82 |

12,46 |

0,70 |

0,49 |

|

CD5: I have the ability to contact the right people to help me with my professional journey. |

0,89 |

13,61 |

0,75 |

0,56 |

|

CD8: I have the ability to identify and seize opportunities for continuing education and personal development. |

0,86 |

14,45 |

0,76 |

0,62 |

|

Factor 2: superior work performance |

|

|

|

|

|

ITS1: I have complete confidence that my abilities and expertise are well-suited for the challenges presented in wealth management assignments. |

1,00 |

|

0,81 |

0,66 |

|

SWP12: I believe in the purpose of my organization. |

1,03 |

15,07 |

0,80 |

0,66 |

|

SWP9: In my view, assessing job performance through competency-based evaluations is vital. |

0,98 |

13,69 |

0,73 |

0,53 |

|

SWP10: I am of the opinion that utilizing competency-based assessment will aid me in determining whether I meet the established criteria for performance. |

0,98 |

13,25 |

0,71 |

0,51 |

|

SWP11: I have a positive perspective on the responsibilities related to managing wealth. |

1,02 |

15,71 |

0,81 |

0,65 |

|

SWP2: I possess a thorough comprehension of the anticipated conduct and actions required on my part. |

0,92 |

14,31 |

0,75 |

0,57 |

|

CD9: Within a year, I have a distinct vision of the goals I want to achieve in my professional journey. |

0,98 |

14,52 |

0,76 |

0,58 |

|

SWP13: The alignment between my personal goals and values and those of my organization is evident to me. |

1,03 |

15,62 |

0,80 |

0,64 |

|

CD10:I have the capacity to set professional objectives for myself that I work hard to accomplish. |

0,91 |

14,30 |

0,75 |

0,57 |

|

Factor 3: intention to stay |

|

|

|

|

|

ITS5: Opportunities for employee advancement are available within my company. |

1,00 |

|

0,77 |

0,59 |

|

ITS4: I am satisfied with the work atmosphere in my current job. |

1,06 |

14,74 |

0,83 |

0,68 |

|

ITS6: I receive support from my supervisors in my current role |

1,10 |

15,39 |

0,87 |

0,73 |

|

ITS7: I experience a stress-free connection with my supervisors. |

0,95 |

12,79 |

0,73 |

0,58 |

|

ITS3: I derive a sense of achievement and satisfaction from my work. |

0,96 |

14,45 |

0,81 |

0,66 |

|

SWP 8: I am of the opinion that the workforce in this particular establishment is adequately equipped to handle and oversee the everyday obstacles that arise. |

0,92 |

12,86 |

0,73 |

0,54 |

|

Factor 4: performance management |

|

|

|

|

|

SWP4: I am provided with coaching to improve my performance at work. |

1,00 |

|

0,73 |

0,54 |

|

Based on my observations, it appears that the employees in my department readily accept and adjust to the frequent changes occurring. |

0,92 |

10,92 |

0,69 |

0,48 |

|

ITS2: I am content with the salary I receive, as it adequately meets my financial requirements. |

0,86 |

9,38 |

0,60 |

0,36 |

|

SWP5: I hold the opinion that the organization’s employees demonstrate commendable performance and efficiency. |

1,01 |

12,04 |

0,77 |

0,60 |

Additionally, there is compelling proof of convergent validity since all Average Variance Extracted (AVE) measurements for job competency, superior work performance, intention to remain with the company, and performance management are higher than 0,50. Furthermore, the AVE for each aspect surpasses the squared correlation coefficients for related inter-constructs. This affirms that there is adequate discriminant validity as per.(36)

EFA and CFA of Job Competency

In order to begin the process, an initial Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted using varimax rotation. After conducting the analysis, four factors were found to account for a combined 61,81 % of the total variance. After conducting Bartlett’s test of sphericity, it was determined that the results were statistically significant. Following Field’s research recommendations from 2005, a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure was computed to assess the adequacy of the sampling, resulting in a value of 0,94. In order to evaluate the dependability scores for each variable, Cronbach’s alpha was employed, and it varied from 0,75 to 0,95, indicating a satisfactory level of internal consistency has been accomplished.

Following the completion of an initial stage, an analysis known as EFA was carried out, which was then followed by a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The findings revealed a strong alignment between the career competency model and the collected data. This was supported by various model fit indices: χ² = 1149,47, df = 514, CFI = 0,90, SRMR = 0,07, and RMSEA = 0,06. Table 3 provides statistical evidence that all standardized estimates of job competency were highly significant (p 0,05). The regression weights for each measure were substantial, with values of 0,75, 0,69, 0,73, and 0,64 respectively.

|

Table 3. CFA results for job competency |

||||

|

|

Estimate |

C.R |

Std factor loading |

SMC |

|

Factor 1: Skills & Attitude |

0,99 |

13,5 |

0,75 |

0,57 |

|

Factor 2: Knowledge |

1,04 |

14,30 |

0,69 |

0,54 |

|

Factor 3: Personality |

1,15 |

10,86 |

0,73 |

0,55 |

|

Factor 4: Behaviour |

0,87 |

7,98 |

0,64 |

0,59 |

Following the completion of a preliminary survey, the EFA analysis was undertaken. Following that, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed to verify the results. A suitable range for the values of Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is typically between 0,5 and 0,6. Additionally, each construct’s AVE value exceeded the squared correlation coefficients with other constructs, confirming reliable discriminant validity. These results are consistent with Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) established guidelines for assessment.

EFA and CFA of Career Success Satisfaction

With Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), researchers were able to uncover a framework that governs the connections within the concept of career contentment. To determine if there was a correlation between variables, an examination of sphericity was conducted using Bartlett’s method, which yielded a significant result. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy also attained a score of 0,88, indicating that there is sufficient data to continue with further analysis.

The scales utilized in this study achieved a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0,90, surpassing the minimum reliability standard of 0,70. This suggests that the items used to assess satisfaction with career success are internally coherent and can be considered reliable indicators for this construct.

By employing EFA and conducting various statistical tests, researchers have gained valuable insights into the framework governing career contentment and have established reliable measures for assessing satisfaction with career success.

After conducting an evaluation, the assessment was expanded by implementing Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The results of this analysis revealed a favorable association between the model and the collected data. Specifically, indicators of compatibility such as χ² = 57, df = 12, CFI = 0,95, SRMR = 0,04, RMSEA = 0,06 were obtained to indicate this correlation.

To evaluate the convergent validity of career success satisfaction, we analyzed the factor loadings and their associated levels of statistical significance. The results, found in table 4, show that all standardized loading estimates were above 0,50 and their corresponding absolute t-values exceeded 1,96. These findings indicate a significant level of convergent validity, consistent with previous studies conducted.(3,42) This indicates that our measurement accurately evaluates satisfaction with career success based on these established benchmarks.

|

Table 4. CFA results for career success satisfaction |

||||

|

|

Estimate |

C.R |

Std factor loading |

SMC |

|

Career success satisfaction (CSS3) |

1,00 |

|

0,79 |

0,42 |

|

Career success satisfaction (CSS7) |

1,11 |

14,11 |

0,80 |

0,44 |

|

Career success satisfaction (CSS2) |

0,98 |

13,58 |

0,77 |

0,57 |

|

Career success satisfaction (CSS4) |

0,99 |

16,21 |

0,73 |

0,54 |

|

Career success satisfaction (CSS6) |

1,11 |

13,21 |

0,75 |

0,60 |

|

Career success satisfaction (CSS8) |

0,83 |

11,33 |

0,66 |

0,64 |

|

Career success satisfaction (CSS9) |

0,89 |

11,03 |

0,65 |

0,63 |

The satisfaction average (AVE) for one’s career, which measured at 0,55, surpassed the 0,50 threshold and went beyond the squared correlation estimate between these measures. These results validate that the concept of career satisfaction possesses both convergent and discriminant validity in an appropriate manner.

Structural Model

The final structural model was tested using the AMOS software package. The model’s fit indices were evaluated and yielded the following results: χ² = 4975,97, df = 2185, CFI = 0,81, SRMR = 0,06, and RMSEA = 0,06. Based on the calculated CFI and GFI values, it can be concluded that the data fits the model adequately. As per study, the confidence interval of the proposed model’s RMSEA value is between ,058 and ,067 at a confidence level of 90 %. This suggests that with a precision level of 90 %, we can confidently say that the true population RMSEA value falls within this range. Taking into consideration these CFI, GFI, and RMSEA values collectively, it is reasonable to conclude that this structural model demonstrates a reasonably favourable fit when applied to our sample data provided here.

After analysing the information provided below, it can be inferred that the path coefficient values, and their associated levels of significance demonstrate positive relationships and statistical importance. This confirms the presence of all established direct positive associations. According to the model, career competency serves as a mediator, connecting perceived wealth career management with career satisfaction.

Different strategies can be utilized to examine mediation hypotheses, although there are informal indicators that can only serve as standards for mediating effects. Baron and Kenny in 1986 introduced a procedure known as the Sobel test, which was originally developed.(72) This test has been expanded upon by researchers over time, leading to the development of various statistical techniques based on it. Some notable works include.(55,56) The found that the Sobel test showed better performance, especially when dealing with sample sizes larger than 50. Considering these factors, it was concluded that the Sobel test would be appropriate for implementation in this study.

Figure 2. Results obtained from the final model structure with a specified path

To analyse the mediation hypotheses in this research, various methodologies were employed. One of these methodologies was the Sobel test, which was first introduced by Sobel in 1982 and then expanded upon.(14) The Sobel test framework has been utilized to develop several statistical methods, including those proposed.(55)

The indirect impact was determined by utilizing the formulas specified.(56) In order to determine the indirect impact, we computed the product of ‘a’, which is the path coefficient indicating the relationship between the exogenous variable and mediator, and ‘b’, which signifies the link between mediator and outcome. The statistical significance of this calculation was assessed using the Sobel test. In table 4 and figure 2, you can find our analysis results on how career development influences satisfaction with career success through mediating effects. During our analysis, we discovered that there was a coefficient of 0,19 for the indirect effect, with a t-value of 3,17 and a p-value of 0,00. Furthermore, we also observed significant findings in relation to superior work performance and satisfaction with career success when considering job competency as a mediator. In this particular case, we identified an indirect effect coefficient of 0,36, along with a t-value of 4,15 and a p-value of 0,00.

In summary, our analysis highlights how certain variables can have an indirect impact on outcomes by utilizing mediators such as job competency or career development pathways to enhance levels of satisfaction with career success.

The confirmation of the mediating role of job competency in the connection between intention to remain and satisfaction with career success is supported by the indirect effect coefficient (0,17) and t-value (3,21). Similarly, the connection between performance management and career success satisfaction is mediated by job competency, as supported by the coefficient for the indirect effect is 0,15, with a t-value of 2,85. In both cases, the calculated indirect effect coefficients indicate a positive trend with statistical significance (p0,05). These findings offer empirical evidence for the mediating role of job competency in these specific situations.

DISCUSSION

The primary objective of this research was to present a fresh and innovative theoretical framework. The aim was to elucidate the role of job competency as a mediator between perceived wealth career management and satisfaction with career success. The research findings shed light on two crucial aspects: firstly, the direct influence of wealth career management on employees’ contentment with their professional accomplishments; and secondly, its supplementary role in enhancing satisfaction through the improvement of job competency.

To improve the efficiency of their employees’ work performance, companies have the choice to employ different approaches for career management. One possible approach is to integrate training and development initiatives, as suggested,(78) as well as fostering collaborative learning initiatives among colleagues, as proposed.(43) Additionally, exposure to developmental assignments(45), as highlighted,(69) along with the use of online training and engagement in career assessments,(17) can further contribute to this endeavour(53). These collective efforts work together to elevate employees’ marketability and ensure their alignment with the evolving trends in their respective industries. This increased marketability, coupled with updated knowledge, establishes a positive correlation with the perception of career success satisfaction.

According to the research conducted,(30) it was emphasized that the adoption of effective career management practices serves a twofold purpose. It not only boosts employees’ competitive job competency and their contentment with career success, but also adds to the overall competence of both the organization and the wider industry. In order to ensure employee satisfaction and success, it is crucial for wealth management firms to offer support and guidance in skill development. Assistance should be provided to help employees enhance their abilities and achieve higher levels of job performance.

The findings of this research offer solid confirmation for the suggested framework and its anticipated connections. In brief, the perception of affluence in career management has a favourable and straightforward impact on job proficiency. Subsequently, job competency directly contributes to enhancing career success satisfaction. Furthermore, the dimensions of career development, superior work performance, intention to stay, and performance management each independently contribute to career success satisfaction. Additionally, job competency plays a mediating role between the four facets of perceived wealth career management (career development, superior work performance, intention to stay, and performance management) and career success satisfaction.

Among these four dimensions of perceived wealth career management, superior work performance emerges as the most influential contributor to job competency, followed by intention to stay, career development, and performance management. In order to promote job competency, it is essential to seamlessly incorporate career training with other career development programs. This integration will help fulfil the long-term career aspirations of employees. Additionally, there is a clear connection between career evaluation and satisfaction with career success.

The study conducted emphasizes the importance of considering strategic planning and enhanced promotion. Furthermore, a study conducted(27,89) have indicated that providing managerial career counselling and mentoring can be beneficial for enhancing the skills of employees. These activities are essential for evaluating the potential of both current and future managers.

It is worth noting the significance of career development initiatives in relation to enhancing career competence. This highlights the importance of implementing practices such as job rotation, as mentioned in.(11) Moreover, it underscores the importance of employing a variety of tactics in advancing one’s career, such as advertising available positions, offering rotational roles, preparing for future leadership transitions, providing alternative career paths, and granting financial assistance.

Overall, this body of research underscores the value of strategic planning and promotion in organizations while emphasizing the benefits of managerial counselling and mentoring programs for skill enhancement among employees. It also highlights various strategies for effective career development that contribute to assessing both current talents and future potential within an organization’s workforce.

In contrast to the other dimensions, career development has a relatively smaller impact on career competence. Yet, it remains a powerful motivator for employees, suggesting a structured development system could help wealth man) assessment companies attract and retain skilled staff. According to(17,1) career assessment plays a significant role in achieving satisfaction and success in one’s career. Career development and training also contribute to this satisfaction. According to research conducted(83,61) mentorship is a valuable tool for personal development. It offers individuals the opportunity to receive constructive feedback that can shape their future endeavours in a meaningful way, fostering growth and providing valuable perspectives. This ultimately leads to increased contentment with career success. It is evident from the research that utilizing career assessment tools alongside mentorship can greatly enhance one’s chances of achieving a fulfilling professional journey.

Drawing upon the findings of this study, the significance of evaluating one’s professional path in enhancing career success satisfaction is affirmed, thus highlighting the crucial role of both formal and informal mentoring. These forms of mentoring encompass advice, discussions, transparent feedback, induction, and 360-degree appraisals. The positive connections identified emphasize how effective career support can raise employee contentment. It is interesting to note that satisfaction is least affected by career training. This outcome urges managers to approach this aspect with careful consideration. In order to meet employees’ strong interest in education and training, it is essential to provide a range of different training opportunities according to research conducted.(52) These should include both pre-employment and on-the-job training programs.

Job competence plays a critical role in determining the satisfaction one derives from achieving career success. It acts as a mediator between various aspects of effective career management, including career development, intention to stay with an organization, and performance management. This study sheds light on the important role played by job competence in achieving career contentment, representing a significant advancement in empirical research. The results are consistent with the hypothesis put forward,(6,7) highlighting the essential importance of job competence. The results suggest that managers have the potential to enhance their employees’ satisfaction by promoting career competence through strategies like mentoring, job rotation, and performance evaluation. Both individuals and wealth management firms are advised to actively invest in improving their skill sets through activities such as career navigation, networking, and continuous learning opportunities. By doing so, they can increase their level of competency and ultimately experience greater fulfilment from their careers.

CONCLUSIONS

The study enriches career knowledge, highlighting job competence’s mediating role. While prior research identified job competence as a career success predictor,(32) its mediating function lacked empirical support. This study establishes job competence as both a direct and mediating factor between wealth career management and success satisfaction. The four dimensions of wealth career management’s effects on job competence and success satisfaction provide valuable insights. Given limited research on wealth career management, this study’s findings significantly contribute and lay a foundation for future exploration.

Practically, the findings urge companies to retain and enhance staff competence. Effective career management sustains and retains talented.(80) To achieve this, wealth management companies must align career management with objectives. Clear career paths for wealth managers across departments and multinational groups would enhance their competence, benefiting wealth management companies’ competitive edge. Individuals too can elevate competence and satisfaction by participating in activities related to managing one’s career, resulting in greater career goals, skill development, and networking.(65) Wealth management companies and employees must therefore prioritize career competence development.

A significant drawback of this research pertains to the utilization of a fragmented consolidation framework, which combines unique characteristics from individual components within a specific framework. Bagozzi(12) have pointed out that this approach tends to obscure the distinct attributes present in each element. Given the complex nature of the job competency concept, which encompasses various variables, the decision was made to employ partial aggregation in order to simplify the model. Although this approach assists in handling intricate situations and attaining research goals, it does involve the drawback of examining a comprehensive framework that encompasses secondary elements. To overcome this limitation, future studies should concentrate on examining the intermediate effect of each specific aspect of job proficiency individually. It is important to consider another limitation, which pertains to the potential influence of individuals on employees’ competence growth. Since individuals also play a role in job competency and satisfaction with career success, it would be interesting for future research to explore how individual-related factors affect job competency. The results obtained from these types of studies may provide valuable information especially in the field of wealth management. The impact of salary on career success was examined in a study conducted.(82) It was found that one’s income has a significant influence on their professional achievements.

The chance for advancement is an important factor in achieving success in one’s career, as emphasized by a study.(49) Additionally,(68) investigated the impact of family dynamics on a person’s professional path. Furthermore, the level of job held, as discussed in the study,(49) serves as another predictor of success in one’s profession. These findings emphasize the need for further investigation into how effective wealth management relates to other aspects of achieving a successful career path.

To enhance this research, future investigations can delve deeper into the various factors that influence job competency and its results. Apart from organizational and individual aspects, it is crucial to thoroughly examine how factors like work-life balance, government interventions, and cultural elements affect job competencies. Moreover, there is potential for additional investigation into the correlation between job proficiency and both mental and physical flexibility, as outlined in the research conducted.(80) Conducting these supplementary analyses will contribute to a more holistic comprehension of the topic. Moreover, examining outcomes connected to organizational competencies offers valuable insights. As pointed out,(7) there’s a suggestion that individual career competencies complement an organization’s core competencies, although this concept requires empirical validation.

Additionally, it would be fascinating to explore the cause-and-effect relationships between one’s perception of wealth and their management of their career, as well as how this relates to the secondary aspects of job competence. Given the employment of partial aggregation, identifying the distinctiveness of individual components becomes intricate. In forthcoming research, there’s a need to investigate how perceived wealth career management exerts its influence on each specific category of job competency. Investigating whether the impact of perceived wealth on career management varies among various job competency categories is a potential avenue for research. One alternative is to investigate the different degrees of significance that these aspects hold in regards to achieving success and contentment in one’s career.

Considering the specific concentration of this research on financial institutions located in Kochi, a pertinent question arises regarding the generalizability of the findings to wealth management firms operating in diverse cultural contexts. This consideration prompts future research to investigate career management and competency across wealth management companies encompassing various ownership structures and locations. Comparative outcomes could yield valuable insights for cross-cultural career management strategies.

Exploring the potential links between perceived wealth, career management, and job competency is a promising area for future research. The investigation involves examining the connections between these factors and their effects. Researchers must explore how perceived wealth career management affects various job competency categories, considering the limitation of partial aggregation. This line of research could delve into whether these factors are uniformly influenced or discern their varying impacts on career success satisfaction.

Moreover, the exploration of potential gender disparities in job competency within Kerala, as well as other cultural settings, presents an intriguing opportunity for inquiry.

Additionally, it is advised that researchers delve into the correlation between the demographic traits of financial advisors and their abilities in their profession, dedication to their careers, and views on wealth management. Prior studies have underscored the influence of factors such as age and job tenure on managerial attributes and competencies. These insights offer a foundation for investigating how demographic factors impact job competencies, career commitment, and practices related to wealth career management.

REFERENCES

1. Abraham SE, Karns LA, Shaw K, Mena MA. Managerial competencies and the managerial performance appraisal process. Journal of management development. 2001 Dec 1; 20(10): 842-852.

2. Allen TD, Eby LT, Poteet ML, Lentz E, Lima L. Career benefits associated with mentoring for protégés: A meta-analysis. Journal of applied psychology. 2004 Feb; 89(1): 127–135.

3. Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological bulletin. 1988 May; 103(3): 411-423.

4. Archer KC, Boyle DP. Toward a measure of caregiver satisfaction with hospice social services. The Hospice Journal. 1999 Jun 1; 14(2): 1-5.

5. Armstrong‐Stassen M, Ursel ND. Perceived organizational support, career satisfaction, and the retention of older workers. Journal of occupational and organizational psychology. 2009 Mar; 82(1): 201-220.

6. Arthur MB. The boundaryless career: A new perspective for organizational inquiry. Journal of organizational behavior. 1994 Jul 1: 295-306.

7. Arthur MB, Claman PH, DeFillippi RJ. Intelligent enterprise, intelligent careers. Academy of Management Perspectives. 1995 Nov 1; 9(4): 7-20. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1995.9512032185

8. Arthur MB, Khapova SN, Wilderom CP. Career success in a boundaryless career world. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior. 2005 Mar; 26(2): 177-202.

9. ACAR BÇ, Yüksekdağ Z. Beta-Glycosidase Activities of Lactobacillus spp. and Bifidobacterium spp. and The Effect of Different Physiological Conditions on Enzyme Activity. Natural and Engineering Sciences. 2023 Apr 1; 8(1): 1-7.

10. Ayres H. Career development in tourism and leisure: An exploratory study of the influence of mobility and mentoring. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. 2006 Aug; 13(2): 113-123.

11. Azizi N, Zolfaghari S, Liang M. Modeling job rotation in manufacturing systems: The study of employee’s boredom and skill variations. International journal of production economics. 2010 Jan 1; 123(1): 69-85.

12. Bagozzi RP, Edwards JR. A general approach for representing constructs in organizational research. Organizational research methods. 1998 Jan; 1(1): 45-87.

13. Barley SR. Careers, identities, and institutions: The legacy of the Chicago School of Sociology. Handbook of career theory. 1989 Aug 25; 41: 41-65.

14. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1986 Dec; 51(6): 1173-1182.

15. Baruch Y, Rosenstein E. Human resource management in Israeli firms: Planning and managing careers in high technology organizations. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 1992 Dec 1; 3(3): 477-495.

16. Baruch Y. Organizational career planning and management techniques and activities in use in high‐tech organizations. Career Development International. 1996 Feb 1; 1(1): 40-49.

17. Baruch Y. Career systems in transition: A normative model for organizational career practices. Personnel review. 2003 Apr 1; 32(2): 231-251.

18. Baruch Y. Career development in organizations and beyond: Balancing traditional and contemporary viewpoints. Human resource management review. 2006 Jun 1; 16(2): 125-138.

19. Baruch Y, Peiperl M. Career management practices: An empirical survey and implications. Human resource management. 2000 Dec; 39(4): 347-366.

20. Bateman TS, Crant JM. The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. Journal of organizational behavior. 1993 Mar; 14(2): 103-118.

21. Blancero D, Boroski J, Dyer L. Key competencies for a transformed human resource organization: Results of a field study. Human resource management. 1996 Sep; 35(3): 383-403.

22. Bowen DD, Hall DT. Career planning for employee development: A primer for managers. California Management Review. 1977 Dec; 20(2): 23-35.

23. Burke RJ. Managerial women’s career experiences, satisfaction and well‐being: a five country study. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal. 2001 Dec 1; 8(3/4): 117-133.

24. Burke RJ, McKeen CA. Work experiences, career development, and career success of managerial and professional women. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 1995; 10(4): 81–96.

25. Campbell RJ, Moses JL. Careers from an organizational perspective. Career development in organizations. 1986: 274-309.

26. Campion MA, Cheraskin L, Stevens MJ. Career-related antecedents and outcomes of job rotation. Academy of management journal. 1994 Dec 1; 37(6): 1518-1542.

27. Chao GT, Walz P, Gardner PD. Formal and informal mentorships: A comparison on mentoring functions and contrast with nonmentored counterparts. Personnel psychology. 1992 Sep; 45(3): 619-636.

28. Chong E. Managerial competencies and career advancement: A comparative study of managers in two countries. Journal of business research. 2013 Mar 1; 66(3): 345-353.

29. Chen HC, Naquin SS. An integrative model of competency development, training design, assessment center, and multi-rater assessment. Advances in Developing Human Resources. 2006 May; 8(2): 265-282.

30. DeFillippi RJ, Arthur MB. The boundaryless career: A competency‐based perspective. Journal of organizational behavior. 1994 Jul; 15(4): 307-324.

31. DeNisi AS, Murphy KR. Performance appraisal and performance management: 100 years of progress?. Journal of applied psychology. 2017 Mar; 102(3): 421-433.

32. Eby LT, Butts M, Lockwood A. Predictors of success in the era of the boundaryless career. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior. 2003 Sep; 24(6): 689-708.

33. Ellenbecker CH. A theoretical model of job retention for home health care nurses. Journal of advanced nursing. 2004 Aug; 47(3): 303-310.

34. Evangelidis, K. Performance measured is performance gained, The Treasurer, 1992: 45-47.

35. Field AP. Is the meta-analysis of correlation coefficients accurate when population correlations vary?. Psychological methods. 2005 Dec; 10(4): 444-467.

36. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981; 18(3): 382-388.

37. Gakovic A, Yardley K. Global talent management at HSBC. Organization Development Journal. 2007 Jul 1; 25(2): P201-P205.

38. George JM, Jones GR. Experiencing work: Values, attitudes, and moods. Human relations. 1997 Apr; 50(4): 393-416.

39. Agina-Obu R, Oyinkepreye Evelyn SG. Evaluation of Users’ Satisfaction of Information Resources in University Libraries in Nigeria: A Case Study. Indian Journal of Information Sources and Services, 2023; 13(1): 1–5.

40. Greenhaus JH, Parasuraman S, Wormley WM. Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of management Journal. 1990 Mar 1; 33(1): 64-86.

41. Gutteridge TG, Leibowitz ZB, Shore JE. When careers flower, organizations flourish. Training & Development. 1993 Nov 1; 47(11): 24-30.

42. Hair JF. Multivariate data analysis. 2009.

43. Hall DT. The Career Is Dead--Long Live the Career. A Relational Approach to Careers. The Jossey-Bass Business & Management Series. Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers, 350 Sansome Street, San Francisco, CA 94104. 1996.

44. Sotnikova O. Zhidko E, Prokshits E, Zolotukhina I. Administration of Sustainable Development of Territories as One of the Approaches for Creating A Biosphere-Compatible and Comfortable Urban Environment. Arhiv za tehničke nauke, 2022; 1(26): 79–90.

45. Higgins MC, Kram KE. Reconceptualizing mentoring at work: A developmental network perspective. Academy of management review. 2001 Apr 1; 26(2): 264-288.

46. Houssein AA, Singh JS, Arumugam T. Retention of employees through career development, employee engagement and work-life balance: An empirical study among employees in the financial sector in Djibouti, East Africa. Global Business and Management Research. 2020 Jul 1; 12(3): 17-32.

47. Liebowitz J, Agresti W, Djavanshir GR. Communicating as IT professionals. Prentice-Hall, Inc.; 2005 Aug 1.

48. Aziz B, Hamilton G. Enforcing reputation constraints on business process workflows. Journal of Wireless Mobile Networks, Ubiquitous Computing, and Dependable Applications. 2014 Mar; 5(1): 101-121.

49. Judge TA, Bretz Jr RD. Political influence behavior and career success. Journal of management. 1994 Mar 1; 20(1): 43-65.

50. Judge TA, Higgins CA, Thoresen CJ, Barrick MR. The big five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Personnel psychology. 1999 Sep; 52(3): 621-652.

51. Kagioglou M, Cooper R, Aouad G. Performance management in construction: a conceptual framework. Construction management and economics. 2001 Jan 1; 19(1): 85-95.

52. Kong H, Cheung C, Qiu Zhang H. Career management systems: what are China’s state‐owned hotels practising?. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2010 Jun 1; 22(4): 467-482.

53. Kossek EE, Roberts K, Fisher S, Demarr B. Career self‐management: A quasi‐experimental assessment of the effects of a training intervention. Personnel psychology. 1998 Dec; 51(4): 935-960.

54. Kucherov D, Zavyalova E. HRD practices and talent management in the companies with the employer brand. European Journal of training and Development. 2012 Jan 27; 36(1): 86-104.

55. MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation review. 1993 Apr; 17(2): 144-158.

56. MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate behavioral research. 1995 Jan 1; 30(1): 41-62.

57. McClelland DC, Boyatzis RE. Leadership motive pattern and long-term success in management. Journal of Applied psychology. 1982 Dec; 67(6): 737-743.

58. McCloskey JC, McCain BE. Satisfaction, commitment and professionalism of newly employed nurses. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1987 Mar; 19(1): 20-24.

59. McMahon M, Watson M, Patton W. Context-resonant systems perspectives in career theory. Handbook of career development: International perspectives. 2014: 29-41.

60. Mirabile RJ. Everything you wanted to know about competency modeling. Training & development. 1997 Aug 1; 51(8): 73-78.

61. Murphy SE, Ensher EA. The role of mentoring support and self-management strategies on reported career outcomes. Journal of Career development. 2001 Jun; 27: 229-246.

62. Nabi GR. An investigation into the differential profile of predictors of objective and subjective career success. Career development international. 1999 Jul 1; 4(4): 212-225.

63. Näppä A, Farshid M, Foster T. Employer branding: Attracting and retaining talent in financial services. Journal of Financial Services Marketing. 2014 Jun 1; 19: 132-145.

64. Ng TW, Eby LT, Sorensen KL, Feldman DC. Predictors of objective and subjective career success: A meta‐analysis. Personnel psychology. 2005 Jun; 58(2): 367-408.

65. O’Brien D, Gardiner S. Creating sustainable mega event impacts: Networking and relationship development through pre-event training. Sport Management Review. 2006 May 1; 9(1): 25-47.

66. Orpen C. The effects of organizational and individual career management on career success. International journal of manpower. 1994 Feb 1; 15(1): 27-37.

67. Price JL, Mueller CW. A causal model of turnover for nurses. Academy of management journal. 1981 Sep 1; 24(3): 543-565.

68. Schneer JA, Reitman F. Effects of alternate family structures on managerial career paths. Academy of Management Journal. 1993 Aug 1; 36(4): 830-843.

69. Seibert SE, Crant JM, Kraimer ML. Proactive personality and career success. Journal of applied psychology. 1999 Jun; 84(3): 416-427.

70. Shader K, Broome ME, Broome CD, West ME, Nash M. Factors influencing satisfaction and anticipated turnover for nurses in an academic medical center. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2001 Apr 1; 31(4): 210-216.

71. Shet SV, Patil SV, Chandawarkar MR. Competency based superior performance and organizational effectiveness. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management. 2019 Jun 10; 68(4): 753-773.

72. Shih KH, Liu YT, Jones C, Lin B. The indicators of human capital for financial institutions. Expert Systems with Applications. 2010 Mar 1; 37(2): 1503-1509.

73. Shippmann JS, Ash RA, Batjtsta M, Carr L, Eyde LD, Hesketh B, Kehoe J, Pearlman K, Prien EP, Sanchez JI. The practice of competency modeling. Personnel psychology. 2000 Sep; 53(3): 703-740.

74. Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological methodology. 1982 Jan 1; 13: 290-312.

75. Spencer LM, Spencer S. Competence at Work: Models for Superior Performance, Wiley, New York, NY. 1993.

76. Stasz C. Assessing skills for work: two perspectives. Oxford economic papers. 2001 Jul 1; 53(3): 385-405.

77. Stebbins RA. Career: The subjective approach. The Sociological Quarterly. 1970 Jan 1; 11(1): 32-49.

78. Sullivan SE, Carden WA, Martin DF. Careers in the next millennium: Directions for future research. Human Resource Management Review. 1998 Jan 1; 8(2): 165-185.

79. Suutari V, Mäkelä K. The career capital of managers with global careers. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2007 Sep 25; 22(7): 628-648.

80. Tams S, Arthur MB. The boundaryless career. In Encyclopedia of career development. Sage Publications. 2006: 44-49.

81. Taunton RL, Boyle DK, Woods CQ, Hansen HE, Bott MJ. Manager leadership and retention of hospital staff nurses. Western journal of nursing research. 1997 Apr; 19(2): 205-226.

82. Tharenou P. Going up? Do traits and informal social processes predict advancing in management?. Academy of management Journal. 2001 Oct 1; 44(5): 1005-1017.

83. Uhl-Bien M. Relationship development as a key ingredient for leadership development. InThe future of leadership development. Psychology Press. 2003 Sep 12: 155-174.

84. Obeidat A, Yaqbeh R. Business Project Management Using Genetic Algorithm for the Marketplace Administration. Journal of Internet Services and Information Security. 2023; 13(2): 65-80.

85. Verdú‐Jover AJ, Gómez‐Gras JM, Lloréns‐Montes FJ. Exploring managerial flexibility: determinants and performance implications. Industrial Management & Data Systems. 2008 Feb 1; 108(1): 70-86.

86. Wang R, Tseng ML. Evaluation of international student satisfaction using fuzzy importance-performance analysis. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2011 Jan 1; 25: 438-446.

87. Weng Q, McElroy JC, Morrow PC, Liu R. The relationship between career growth and organizational commitment. Journal of vocational behavior. 2010 Dec 1; 77(3): 391-400.

88. Weng Q, McElroy JC. Organizational career growth, affective occupational commitment and turnover intentions. Journal of vocational behavior. 2012 Apr 1; 80(2): 256-265.

89. Williams J, Forgasz H. The motivations of career change students in teacher education. Asia‐Pacific Journal of Teacher Education. 2009 Feb 1; 37(1): 95-108.

90. Woodruffe C. What is meant by a competency?. Leadership & organization development journal. 1993 Jan 1; 14(1): 29-36.

91. Zaim H, Tatoglu E, Zaim S. Performance of knowledge management practices: a causal analysis. Journal of knowledge management. 2007 Oct 30; 11(6): 54-67.

FINANCING

No financing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Benil Dani Alexander, S. Vasantha, M. Thaiyalnayaki.

Formal analysis: Benil Dani Alexander, S. Vasantha, M.Thaiyalnayaki.

Research: Benil Dani Alexander, S. Vasantha, M. Thaiyalnayaki.

Writing - Original Draft: Benil Dani Alexander, S. Vasantha, M. Thaiyalnayaki.

Writing - Proofreading and Editing: Benil Dani Alexander, S. Vasantha, M. Thaiyalnayaki.