Category: Finance, Business, Management, Economics and Accounting

ORIGINAL

Un análisis empírico del efecto del comportamiento del usuario basado en el marketing de la moda sostenible

An Empirical analysis of the effect of user behavior based on marketing sustainable fashion

Beeraka Chalapathi1,2

![]() *, G. Rajini2

*, G. Rajini2

![]() *

*

1National Institute of Fashion Technology, Tharamani, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India.

2School of Management Studies, Vels Institute of Science Technology Advanced Studies (VISTAS). Pallavaram, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India.

Cite as: Chalapathi B, Rajini G. An Empirical analysis of the effect of user behavior based on marketing sustainable fashion. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2024; 3:883. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2024883

Submitted: 03-02-2024 Revised: 19-04-2023 Accepted: 10-06-2024 Published: 11-06-2024

Editor: Dr.

William Castillo-González ![]()

ABSTRACT

User behavior has had a significant impact on the fashion sector’s marketing strategy. Environmental knowledge, market attitude, social conditioning, and value perception worth all had a favorable influence on the buying, but market attitude had the significant impacts. This study used a decision-making model that encompassed cognition, emotive, and behavior intentions to examine customer behavior of product consumer engagement. On the questionnaires, the demographic and hypothesis measurement items were separated. Only 370 of the 500 persons who applied have any previous experience shopping in the fashion industry. The major factors used to measure hypotheses are Promotional Strategy, Customer Satisfaction, Relationship Satisfaction, Purchase Intent, Loyalty Intention, and Participation Intention. All elements were evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale to measure from 1 – 5. This study also suggests that in order to achieve marketing goals and achieve long-term effectiveness for businesses, marketing content should be followed by Marketing Activity (MA) and Customer Experience (CE).

Keywords: User Behavior; Fashion Industry; Loyalty Intention; Hypothesis; Purchase Intention; Customer Experience; Participate Intention; Marketing Activity; Sustainable Performance; Relationship Quality.

RESUMEN

El comportamiento del usuario ha tenido un impacto significativo en la estrategia de marketing del sector de la moda. El conocimiento del entorno, la actitud ante el mercado, el condicionamiento social y la percepción del valor influyeron favorablemente en la compra, pero la actitud ante el mercado fue la que tuvo un impacto significativo. Este estudio utilizó un modelo de toma de decisiones que englobaba las intenciones cognitivas, emotivas y de comportamiento para examinar el comportamiento del consumidor de productos. En los cuestionarios se separaron los ítems demográficos y los de medición de hipótesis. Sólo 370 de las 500 personas que se presentaron tenían experiencia previa en compras en el sector de la moda. Los principales factores utilizados para medir las hipótesis son la estrategia promocional, la satisfacción del cliente, la satisfacción de la relación, la intención de compra, la intención de fidelización y la intención de participación. Todos los elementos se evaluaron utilizando una escala Likert de 5 puntos para medir de 1 a 5. Este estudio también sugiere que, para alcanzar los objetivos de marketing y lograr la eficacia a largo plazo para las empresas, el contenido de marketing debe ir seguido de la Actividad de Marketing (AM) y la Experiencia del Cliente (EC).

Palabras clave: Comportamiento del Usuario; Industria de la Moda; Intención de Fidelización; Hipótesis; Intención de Compra; Experiencia del Cliente; Intención de Participar; Actividad de Marketing; Rendimiento Sostenible; Calidad de la Relación.

INTRODUCTION

After automobiles and technology, fashion is said to be the third in the world manufacturing sector.(1) Every year, almost 150 billion units of outerwear are produced around the world.(2) Fashion is best defined as the styles of outfits preferred by parts of the population only at one time, according to several recent House of Commons investigation.(3) Might there remains the possibility among high-end designer outerwear displayed in New York or Paris Street and mass-produced sports and casual wear sold in clothing stores and economies around the world. The fashion industry, on the other side, involves the advertising, production, design, retailing, distribution, marketing, and promotion of all types of garments, from haute couture to everyday wear.(4)

Many fashion brands, like GAP, Muji, H&M, Levi Strauss, Nike, Muji, and GAP, and had invested in and developed sustainable fashion product items in reducing the environmental impact and project a positive reputation. Sustainability clothing, often described as eco-fashion or ecological fashion, consists of items created and sold with the purpose of environmental protection.(5) Companies might having a positive influence on the company providing the develop environmental policy to solve certain sustainability challenges that might cause. Several steps will help businesses expand and save money while also raising the overall advantage.(6) Although fashionable clients are often more mindful of nature conservation, civic conscience, and financial viability, the firm’s long-term future has been taken into account.(7)

This fashion industry, on the other hand, generates a lot of waste and exerts a substantial burden on the environment.(8) Annually, around $500 billion is frittered due to clothing underuse and a deficiency of recovery.(9) By 2030, global clothing usage is anticipated to rise from 62 billion metric tons to 102 million metric tons.(10) Moreover, trash from fashion goods, also including textiles, solvents, and pigments, causes pollution and contributes to temperature shift. Fashion brands are also one of the greatest ecological footprint in the present uni - directional globalized supply chain, creating even further greenhouse gas emissions than the airline and maritime areas combined, due to the fact that virtually all fashion items are outsourced and delivered worldwide. When considering the entire life cycle of clothing, the fashion industry is estimated to be responsible for 3,3 billion tons of Carbon dioxide emission and 20 % of worldwide industrial effluents.(11)

Finally, we offer management perspectives on how risk aversion impacts the marketing, its participants, and the Pareto improvement measures in the context of rapid reaction. This would be, to anything other than the extent practicable, the very first study of retail outlets’ risk appetite in accelerated fashion supplier relationships. All of the findings are in closed form, and they give crucial theoretical direction to practitioners working with fast-response fashion supply chains.(12,13)

The risk-averse fashion merchant faces a mean-variance optimization issue. The goal is to look at the new product selection dilemma, in which a fashion shop must choose one of several fashion products options when demand forecasts are unclear. When the demand prediction is more accurate, the fashion shop must determine the ideal ordering quantity for the selected new product.(14) Towards the basic model, we show that the best new product selection is highly influenced by the forecasted company’s mean of demand. It’s fascinating to demonstrate that, mostly under basic model, the fashion retailer’s best new consumer decision option is also best for the entire fashion product lifecycle. Owing to the fashion firm’s behavioral biases and the two - fold marginalized effect, the fashion chain’s purchasing choice varies by the fashion supplier’s company’s optimal number. As a conclusion, we have developed a Markdown Sponsor Tariff (MST) contract and demonstrated that it might able to complete production chain management using the basic model. Throughout the expansive approach, that correlates to the scenario with a fixed cost,(15) we find that the fashion retailer’s optimized new product variety is generally different from the fashion marketing’s ideal unique product applicant.

Theoretical framework

Within the fashion business, sustainability marketing has been a popular topic of discussion. Since there has been a rise in awareness of this issue, particularly in the last decade, several fashion businesses have begun to include sustainability components in their goods.

Sustainable Fashion Marketing

The term “sustainability,” as defined,(16) corresponds to an eco-balance that strives to preserve a balance between economic growth and humanity as resource retail customers. The number of resources we used should not be larger than the number of resources that can be renewed(17) have discussed. The utilization of renewable and sustainable and environment raw materials, carbon reduction, durability, and lifespan are all examples of environmental sustainability in fashion.

Eco - friendly product enterprises,(18) use the green supply chain technique to deal with the following demands for sustainable production (GSCM). GSCM is the process of incorporating environmental factors into supplier relationships, which incorporates multiple design, substrate acquisition and procurement, manufacturing, finished product redistribution to consumers, and item end-of-life administration.(19)

Sustainable marketing,(20) is about much more than doing an environmentally accountable action, but it also provides a tremendous opportunity for businesses. Armstrong Soule,(21) for example, have presented One on either hand, green de-marketing is an advertising strategy that encourages clients to decrease their demand in the area environmentally sustainable. Wang(22) have provided corporate sustainability, according to a prior study, has a significant effect on consumer profits.

Marketing Activity

Jung(23) have discussed stated that three variables should be considered while developing sustainable marketing strategies: economic, social, and environmental. Syaekhoni(24) have proposed Corporate sustainability refers to a firm’s decision-making procedures and activities, such as manufacturers and distributors, as well as its sociocultural and ecologically friendly principles, and even the local community in general and consumers’ choice systems and processes. The goal of cultural activities is to recognize the diversity of cultures.

Bărbulescu(25) have presented Companies utilize sustainability management initiatives to reach closer to customers as society’s interest in sustainability rises. Martínez(26) have discussed Economic marketing operations entail distributing economic gains within an area through economic assistance. Customers, workers, partners, and community stakeholders should all gain financially from the activity, which should also encourage corporate growth through revenues.

Hategan(27) have proposed say that profits should be generated through innovative goods and services, and earnings should be shared with local stakeholders, based on innovation, value creation, and efficient management. Revenue growth is also boosted by economic responsibility. Oláh(28) Thus, via the construction of an e-commerce environment, the enhancement of shop environments, and the upgrading of facilities, economic marketing operations should optimize profits based on management efficiency.

Customer Behavioral Outcomes

The purpose of this study,(29) is to investigate the effects of self-identity, behavioral intention, and perspectives on the intent to buy popular fashion products. Also, it illustrates how a merchant’s willingness to pay a fortune for high end fashion items is impacted by their purchasing purpose. Aside from the link among self-identity and buying trends, ideas on that research include the links between self-identity, facilitating conditions, and mentality and repurchase behavior and value perception.

Lemon,(30) as example, having spoken about As per recent study, customer perception is a complex term used to denote a customer’s intellectual, psychological, behavioral, physical, and social experiences to a brand or company during their buying journey. According to,(31) Online products are thought to deliver a negative experience but to the inability to compete with retail workers and the lack of face-to-face interaction. Keiningham(32) have presented that CX is among the most important frameworks that a manager should examine when identifying and acting on chances to improve the company’s competitive position.

Relationship Quality

Shetty(33) have discussed Within the disciplines of service marketing and industrial marketing, the relationship marketing idea arose. Neculaesei(34) have proposed explain that the establishment of relationships between two parties, namely service providers and customers, is the main focus of the marketing relationship.

Nikbin(35) have presented highlight that the degree to which trust is a component of relationship quality is determined by the type of message conveyed by the company. A positive relationship relies heavily on the quality of one’s relationships. Lee(36) have discussed Relationship quality has been defined as a composite or multidimensional entity with three unique but linked components: trust, satisfaction, and commitment.

The study recommended,(37) meanwhile, focuses entirely on confidence and satisfaction. The primary reason why solely confidence and satisfaction were included in the consumer - based brand equity constructs: To begin with, much prior research focused at relationship satisfaction as a second-order construct of trust, with contentment as a feature. The bulk of previous research regards relationship quality as a mediator between its causes and effects, according to,(38) As per a study, the effects of social support and blog site efficiency on the willingness to use social commerce and the continuous use of social networking sites is mediated by the quality of the user’s engagement with the social networking website.

Consumer Intention

Consumer Experience (CE) is a complex concept that exemplifies the buyer’s perceptual, emotional, behavioral, sensory, and socio - cultural responses to the corporation’s products or services before the consumer’s buyer ’s journey. This was one of the important methodologies that should be taken into account by the team to evaluate and exploit knowledge that improve the company’s current strategic environment. There are five different sorts of customer experiences, which are listed below:

· Sense: The major sensation that can impact a consumer’s purchasing intention are sight, hearing, aroma, flavor, and feel. Nevertheless, because the SNS’s interface design lacked taste, aroma, and touch, visuospatial inputs are important decision variables in whether or not to utilize.

· Feel: Consumers’ internal feelings and perceptions that may occur as a result of seeing experience words, audio, & photos that create a genuine connection with clients and provider suppliers, causing consumers to engage to the products as well as provide positive affective response.

· Think: Such type of interaction is designed to encourage users to know new things, possible to gain a basic understanding of the expertise and increase their engagement as a byproduct of the promotional strategy.

· Act: Such sort of lifestyle features a lot of behavior options, such as physical fitness, lifestyles, and participation. Social cognitive events in a customer’s daily life leave an indelible impression or trigger an immediate subliminal response.

· Relate: This mode of view connects the personality with people or cultures, transcending interpersonal and emotional thoughts. Following this encounter, the individual and a broader social framework create a bond.

Purchase Intention

Chetioui,(39) have talked about this. A surge in intentions, as shown in the TPB, indicates a greater possibility of following out the behavior. In the area of digital advertising, previous research indicates that consumers’ thoughts about a company have a significant affect on the buy expectation.

According to,(40) e-word of mouth (e-WOM) is more effective when supplied by well individual people and has a considerable influence on internet consumers’ purchasing intention while offered by well individual people. Brand personality, brand recognition, durability, product evaluation, attributes, and brand equity have all been shown to have a substantial influence on purchasing intent in previous studies.

Loyalty Intention

Jung(41) define “A strong inclination to buy or visit a constant, preferred product or service, even if the customer is in a position that may prompt a conversion action to choose another brand”, according to loyalty. Customers can show loyalty by refusing to transfer brands when they are under duress. As a result, loyalty is defined as the purchase or reuse of a certain product or service on a regular basis or the consumption of the same brand over and over again.

Du(42) have presented that loyalty may assist businesses in establishing a consistent client base, lowering acquisition and transaction costs, and reducing revenue volatility. Other advantages include cheaper marketing expenses, a larger number of clients, a larger market share, and a readiness to pay higher rates.

Participation Intention

Chae(43) have discussed the notion of customer engagement in the service marketing field has been researched by splitting it into two categories: “partial employee” and “co-producer.” However, when it comes to internet marketing, the old difference between the two is no longer valid. Customers assume the position of co-producer in the online environment, bringing new ideas and recommending improvements for a firm, as well as partly employees, doing actions that are anticipated by the organization.

Su(44) have proposed that actions were divided into four categories: preparation for service, employee/company relationship development, information exchange, and intervention in service. Given that the findings show that consumer engagement affects brand equity and relationship equity, the definitions and metrics appear to be inconsistent(46). Operational definitions in shown in table 1.

|

Table 1. Operational definitions |

||

|

Constructs |

Definitions |

Reference |

|

Consumer Experience (CE) |

The degree to which people participate in and see marketing information, which may have sensory, emotional, and cognitive effects that improve attraction, motivation, and recognition, and hence provide value. |

(29,30,31,32) |

|

Participate Intention (PrI) |

After viewing marketing content, customers are more likely to offer a product review, program, or event hosted by the company. |

(43,44) |

|

Loyalty Intention (LI) |

After viewing promotional materials, customers’ inclination to be loyal and committed customers increases. |

(41,42) |

|

Purchase Intention (PI) |

After seeing promotional materials, customers are more likely to buy a product or service. |

(39,40) |

|

Relationship Quality (RQ) |

Fashion stores’ promotional material depends on the extent of total assessment of the strength of a relationship between users and the firm, which includes collaborative intents, mutual transparency, and carry communication. |

(33,34,35,36,37,38) |

|

Marketing Activity (MA) |

Evaluating the mentality of consumers’ comprehension or impression of a company’s marketing efforts. |

(23,24,25,26,27,28) |

Hypothesis Development

Marketing’s main goal is to improve interaction between a firm and its customers, which can result in a favorable relationship and increased interest in what the company has to offer. Client trust is particularly important in the fashion marketing scenario due to the lack of products aesthetic value. Trust is influenced by a company’s reputation in social commerce activities. The level of trust and contentment in a connection is evaluated. The hypotheses are mentioned below:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Relationship quality is positively related to loyalty intention

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Relationship quality is positively related to participation intention

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Relationship quality is positively related to purchase intention

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Marketing Activity is positively related to relationship quality

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Consumer Experience is positively related to relationship quality

Research methodology

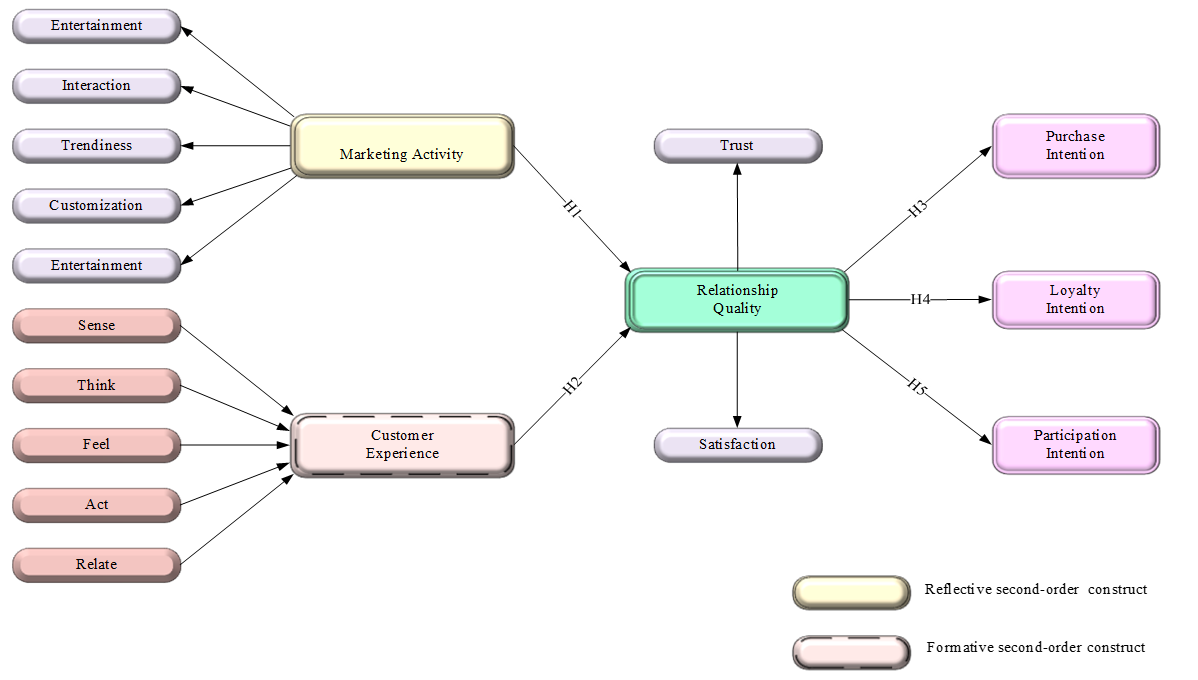

Self-assessment questionnaires were utilized to collect information. The respondents are members of the general public who have shopped for clothes in the past. Filtering of the data was done to exclude inexperienced users. The demographic and hypothesis measurement items were separated on the questionnaires. Only 370 of the 500 people who want to fill out the application have any experience shopping in the fashion business. Figure 1 depicts the research framework for the generated hypothesis.

Figure 1. Research framework of hypothesis development

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The SPSS AMOS program was used for measurement and analysis. The information was gathered via 500 surveys, 130 of which were incomplete and 370 of which had response-set issues. The questionnaires were eliminated after 173 males and 177 females completed them. The goal of the purpose of this research was to look into the connection among the variables of the model stated in the hypothesis using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). As previously stated, the goal was to see if and how important, expectations, and social impact affected customers’ desire to participate in marketing activities. Open-response questions were used to create the questionnaire. This study looked at the relationship between Marketing Program, Customer Satisfaction, Relationship Quality, Purchasing Behavior, Brand Loyalty, and Engagement Intention were all measured using a variety of parameters. Questionnaire measurement items shown in table 2.

|

Table 2. Questionnaire measurement items |

|

|

Factors |

Measurement Items |

|

Marketing Activity (MA) |

|

|

MA1 |

I buy a product because the contents displayed are intriguing. |

|

MA2 |

I buy a product because it allows me to participate in a discussion or leave a comment. |

|

MA3 |

I buy a product because it allows me to participate in a discussion or leave a comment. |

|

Consumer Experience (CE) |

|

|

CE1 |

My curiosity is piqued by the stylish product store. |

|

CE2 |

The company’s product store elicits an emotional response from me. |

|

CE3 |

The stylish product store is attempting to make me reconsider my lifestyle. |

|

Relationship Quality (RQ) |

|

|

RQ1 |

How satisfied are you with trend-driven clothes shopping? |

|

RQ2 |

I was happy with my shopping environment in fashion stores. |

|

RQ3 |

If I needed assistance, the shopkeeper would do everything possible to assist me. |

|

Purchase Intention (CI) |

|

|

PI1 |

In the future, I would consider purchasing items from a fashion store. |

|

PI2 |

I’m likely to make a buy from a fashion store in the near future. |

|

PI3 |

I’m inclined to purchase a specific item from a fashion store. |

|

Loyalty Intention (LI) |

|

|

LI |

Mostly in future, I will acquire more item from there. |

|

L2 |

Definitely might promote the products to my relatives and friends. |

|

L3 |

One amongst my buying avenues will continue to be online communication. |

|

Participation Intention (PrI) |

|

|

PrI |

Whenever a colleague wishes to buy something in a fashion store, I’m prepared to offer my advice and guidance. |

|

Pr2 |

I would “comment” on a tweet from that social networking business that I found interesting. |

|

Pr3 |

I’m likely to tell my friend what goods in the store is worth buying. |

Multiple routes and relationships of MA, CE, RQ, PI, LI, and PrI were identified in this study framework, which is considered a complicated model. The sample size for the SEM analysis should be at least 5 to 10 times the entire route in the model. The sample size in this study was 370, with a total of 5 pathways, which met the fit criteria and was eligible for SEM analysis. Second, CE has been recognized as a second-order formative concept in previous studies. SEM is also superior to covariance-based PLS because it may analyze reflective and formative indicators at the same time. Other analytical approaches, on the other hand, can only evaluate reflected signs.

Validation and Outer Model

Composite reliability, convergent and discriminant, and reliability of the constructs were all explored in the model fit. The composite reliability criteria values for all constructs were 0,7 or above, indicating satisfactory construct reliability. If the predictor factor loading surpasses 0,3 and the AVE reaches 0,5, a construct has convergent validity, according to,(45) The factor loading and reliability test analysis findings are shown in table 3. In discriminant validity, the amount of discriminating between measured variables and distinct construct criteria is determined Once the factor load of each latent component for each set of requirements is more than the latent variables of another framework, each factor indicated sufficient convergent validity.

|

Table 3. Analysis results of reliability and convergent validity |

|||

|

Factors Affecting Measurement |

Loading Factor |

Reliability Composite |

AVE |

|

Marketing Activity |

|||

|

MA1 |

0,397 |

0,76 |

0,54 |

|

MA2 |

0,541 |

||

|

MA3 |

0,565 |

||

|

Consumer Experience |

|||

|

CE1 |

0,532 |

0,9 |

0,75 |

|

CE2 |

0,737 |

||

|

CE3 |

0,732 |

||

|

Relationship Quality |

|||

|

RQ1 |

0,188 |

0,91 |

0,78 |

|

RQ2 |

0,562 |

||

|

RQ3 |

0,664 |

||

|

Purchase Intention |

|||

|

PI1 |

0,992 |

0,85 |

0,65 |

|

PI2 |

0,971 |

||

|

PI3 |

0,998 |

||

|

Loyalty Intention |

|||

|

LI1 |

0,992 |

0,82 |

0,6 |

|

LI2 |

0,971 |

||

|

LI3 |

0,998 |

||

|

Participate Intention |

|||

|

PrI1 |

0,992 |

0,92 |

0,8 |

|

PrI2 |

0,971 |

||

|

PrI3 |

0,998 |

||

Hypothesis Testing and Inner Model Result

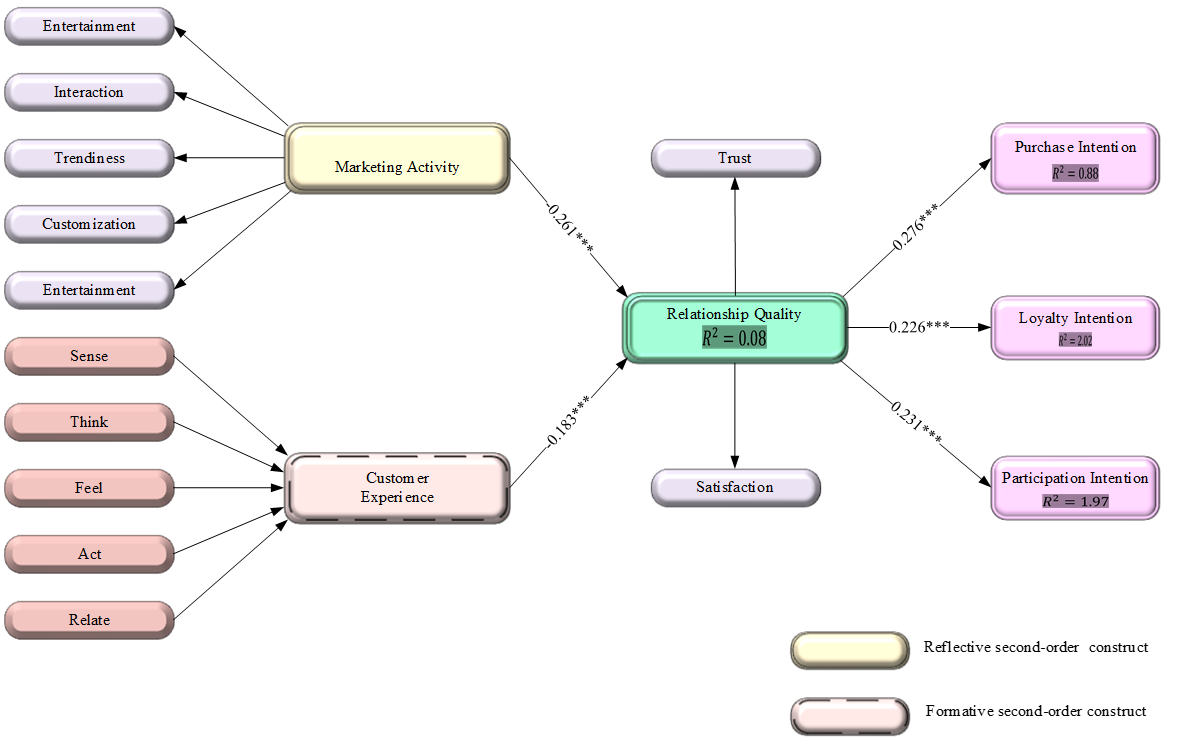

The hypotheses were tested using the inner SEM model analysis. The route of hypotheses is depicted in table 4 with its path coefficient, path p-value, and testing outcomes. The outcomes of the hypothesis testing, in particular, are significant and have a positive value. Figure 2 shows the results that were obtained.

|

Table 4. Results of inner model |

|||||

|

Hypothesis |

H1 |

H2 |

H3 |

H4 |

H5 |

|

Path |

MA --> RQ |

CE --> RQ |

RQ --> PI |

RQ --> LI |

RQ --> PrI |

|

Path coefficient |

-0,261 |

-0,183 |

0,276 |

0,226 |

0,231 |

|

Path p-value |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Result |

Supported |

Supported |

Supported |

Supported |

Supported |

Figure 2. Graphical representation of results achieved for inner model (***be path-value< 0,001)

From the figure 2 and table 4, it is evident that the media activity positively influences Relationship Quality producing H1(MA --> RQ; path coefficient= -0,261; p-value=0,000). Similarly, CE positively impacts RQ with the results of H2(CE --> RQ; path coefficient= -0,183; p-value=0,000). Then RQ positively impacts customer intention, purchase intention, and participation intention resulting H3(RQ --> PI; path coefficient=0,276; p-value=0,000), H4(RQ --> LI; path coefficient= 0,226; p-value=0,000), H5(RQ --> PrI; path coefficient= 0,231; p-value=0,000). The model fit values obtained for the analysis is depicted in table 5.

|

Table 5. The indices’ SEM values |

||

|

Fit-Indices |

Recommend values |

Structural-models |

|

NFI |

≥ 0,90 |

0,996 |

|

RMSEA |

≤ 0,08 |

0,073 |

|

RMSR |

≤ 0,10 |

0,007 |

|

CFI |

≥ 0,90 |

0,997 |

|

AGFI |

≥ 0,90 |

0,944 |

|

GFI |

≥ 0,90 |

0,997 |

|

x2/DF |

≤ 3,00 |

2,95 |

The goodness of fit index (GFI), the adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), the normed fit index (NFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square residual (RMSR), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) are all acronyms for the goodness of fit index. The structural model reflects the realized outcome for all the measured indices, whereas the suggested value in the table denotes goal values for fit indices.

Mediation Effects Testing Results

The statistical validity of the system is defined using path analysis and the Sobel test. The Z-value and t-value of route coefficients for the Sobel test for identifying the indirect effects of hypotheses are shown in table 6. All of the relationships had Z-values more than 2,5, indicating a mediation effect between the dependent and independent factors.

|

Table 6. Mediation test analyzed results |

|||

|

Constructs |

Construct - relationship |

Path coefficient t-value |

Z-value Sobel test |

|

MA --> RQ --> PI |

MA --> RQ |

5,267 |

2,853 |

|

RQ --> PI |

3,367 |

||

|

MA --> RQ --> LI |

MA --> RQ |

5,267 |

2,957 |

|

RQ --> LI |

3,596 |

||

|

MA --> RQ --> PRI |

MA --> RQ |

5,267 |

2,928 |

|

RQ --> PRI |

3,56 |

||

|

CE --> RQ --> PI |

CE --> RQ |

3,68 |

2,497 |

|

RQ --> PI |

3,367 |

||

|

CE --> RQ --> LI |

CE --> RQ |

3,68 |

2,566 |

|

RQ --> LI |

3,596 |

||

|

CE --> RQ --> PRI |

CE --> RQ |

3,68 |

2,547 |

|

RQ --> PRI |

3,56 |

||

CONCLUSION

In the fashion sector, marketing strategy is mostly determined by the quality of the interaction between marketing activity, consumer experience, and purchase, loyalty, and participation intents. Marketing material based on the MA and CE aspects will work together to build a strong relationship between the consumer and the firm, which will influence the customer’s behavior. Relational marketing’s major goal is to improve relationship quality, which may save time and money by keeping current clients. Controlling relation development is important, according to Hypotheses 3–5, since a positive relationship between the customer and the company increases the customer’s inclination to purchase, loyalty, and engagement in the enterprise programme. Additionally, promotional activities can be fulfilled by creating a brand image that is personalized to each individual’s characteristics, some of which are influenced by promotional promotion and advertising material layouts, resulting in a pleasant consumer experience. The mediating test results indicate that service quality is crucial because if a marketing executive can help clients associate themselves with the company’s brand culture, they may strengthen users’ healthy relationships with the companies they prefer and avoid acquiring rivalry goods. Buyers may also be kept as loyal consumers and participate in any event or programme given by the company because of their strong bond. Further, the work can be extended by analyzing the social media marketing strategy in providing impact to the fashion industry.

REFERENCES

1. Zhang B, Zhang Y, Zhou P. Consumer attitude towards sustainability of fast fashion products in the UK. Sustainability. 2021 Feb 4; 13(4): 1646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041646

2. Harman R. Loved Garments: Observed Reasons for Consumers Using and Holding Onto Garments. Art & Design 21: Fashion. 2021 Nov 21: 9.

3. McNeill L, Moore R. Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. International journal of consumer studies. 2015 May; 39(3): 212-222.

4. Čiarnienė R, Vienažindienė M. Management of contemporary fashion industry: characteristics and challenges. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2014 Nov 26; 156: 63-68.

5. Shen B, Zheng JH, Chow PS, Chow KY. Perception of fashion sustainability in online community. The Journal of the textile institute. 2014 Sep 2; 105(9): 971-979.

6. Thorisdottir TS, Johannsdottir L. Sustainability within fashion business models: A systematic literature review. Sustainability. 2019 Apr 13; 11(8): 2233. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082233

7. Yang S, Song Y, Tong S. Sustainable retailing in the fashion industry: A systematic literature review. Sustainability. 2017 Jul 19; 9(7): 1266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071266.

8. Brewer MK. Slow fashion in a fast fashion world: Promoting sustainability and responsibility. Laws. 2019 Oct 9; 8(4): 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws8040024.

9. MacArthur E. A new textiles economy: redesigning fashion’s future. Ellen MacArthur Foundation. 2017: 1-50.

10. Agenda GF. The Boston Consulting Group. Pulse of the fashion industry report 2017. Retrieved 19 Sept, 2019.

11. Beltrami M, Kim D, Rölkens F. The state of fashion 2019.

12. Choi TM. Impacts of retailer’s risk averse behaviors on quick response fashion supply chain systems. Annals of Operations Research. 2018 Sep; 268: 239-257.

13. Camargo LR, Pereira SC, Scarpin MR. Fast and ultra-fast fashion supply chain management: an exploratory research. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. 2020 Jun 8; 48(6): 537-553.

14. Choi TM. Launching the right new product among multiple product candidates in fashion: Optimal choice and coordination with risk consideration. International Journal of Production Economics. 2018 Aug 1; 202: 162-171.

15. Macchion L, Danese P, Vinelli A. Redefining supply network strategies to face changing environments. A study from the fashion and luxury industry. Operations management research. 2015 Jun; 8(1): 15-31.

16. Puspita H, Chae H. An explorative study and comparison between companies’ and customers’ perspectives in the sustainable fashion industry. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing. 2021 Apr 3; 12(2): 133-145.

17. Mukherjee S. Environmental and social impact of fashion: Towards an eco-friendly, ethical fashion. International Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies. 2015; 2(3): 22-35.

18. Lee SY. The effects of green supply chain management on the supplier’s performance through social capital accumulation. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal. 2015 Jan 12; 20(1): 42-55.

19. Bhattacharjee K. Green supply chain management-challenges and opportunities. Asian Journal of Technology & Management Research. 2015 Jan; 5(01): 14-19.

20. Dangelico RM, Vocalelli D. “Green Marketing”: An analysis of definitions, strategy steps, and tools through a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Cleaner production. 2017 Nov 1; 165: 1263-1279.

21. Armstrong Soule CA, Reich BJ. Less is more: is a green demarketing strategy sustainable?. Journal of Marketing Management. 2015 Sep 2; 31(13-14): 1403-1427.

22. Wang H, Ko E, Woodside A, Yu J. SNS marketing activities as a sustainable competitive advantage and traditional market equity. Journal of Business Research. 2021 Jun 1; 130: 378-383.

23. Jung J, Kim SJ, Kim KH. Sustainable marketing activities of traditional fashion market and brand loyalty. Journal of Business Research. 2020 Nov 1; 120: 294-301.

24. Syaekhoni MA, Alfian G, Kwon YS. Customer purchasing behavior analysis as alternatives for supporting in-store green marketing decision-making. Sustainability. 2017 Nov 2; 9(11): 2008. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112008

25. Bărbulescu O, Tecău AS, Munteanu D, Constantin CP. Innovation of startups, the key to unlocking post-crisis sustainable growth in Romanian entrepreneurial ecosystem. Sustainability. 2021 Jan 12; 13(2): 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020671

26. Martínez JB, Fernández ML, Fernández PM. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution through institutional and stakeholder perspectives. European journal of management and business economics. 2016 Jan 4; 25(1): 8-14.

27. Hategan CD, Sirghi N, Curea-Pitorac RI, Hategan VP. Doing well or doing good: The relationship between corporate social responsibility and profit in Romanian companies. Sustainability. 2018 Apr 1; 10(4): 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041041

28. Oláh J, Kitukutha N, Haddad H, Pakurár M, Máté D, Popp J. Achieving sustainable e-commerce in environmental, social and economic dimensions by taking possible trade-offs. Sustainability. 2018 Dec 24; 11(1): 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010089

29. Salem S, Chaichi K. Investigating causes and consequences of purchase intention of luxury fashion. Management Science Letters. 2018; 8(12): 1259-1272.

30. Lemon KN, Verhoef PC. Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of marketing. 2016 Nov; 80(6): 69-96.

31. McLean G, Wilson A. Evolving the online customer experience… is there a role for online customer support?. Computers in human behavior. 2016 Jul 1; 60: 602-610.

32. Keiningham T, Aksoy L, Bruce HL, Cadet F, Clennell N, Hodgkinson IR, Kearney T. Customer experience driven business model innovation. Journal of Business Research. 2020 Aug 1; 116: 431-440.

33. Shetty A, Basri S. Relationship orientation in banking and insurance services–a review of the evidence. Journal of Indian Business Research. 2018 Aug 30; 10(3): 237-255.

34. Neculaesei AN, Tatarusanu M, Anastasiei B, Dospinescu N, Bedrule Grigoruta MV, Ionescu AM. A model of the relationship between organizational culture, social responsibility and performance. Transformations in Business & Economics. 2019 May 5; 18(2A): 42-59.

35. Nikbin D, Marimuthu M, Hyun SS. Influence of perceived service fairness on relationship quality and switching intention: An empirical study of restaurant experiences. Current Issues in Tourism. 2016 Aug 23; 19(10): 1005-1026.

36. Lee Y. Relationship quality and its causal link to service value, satisfaction, and word-of-mouth. Services Marketing Quarterly. 2016 Jul 2; 37(3): 171-184.

37. Jiang Z, Shiu E, Henneberg S, Naude P. Relationship quality in business to business relationships—Reviewing the current literatures and proposing a new measurement model. Psychology & Marketing. 2016 Apr; 33(4): 297-313.

38. Wu SH, Huang SC, Tsai CY, Lin PY. Customer citizenship behavior on social networking sites: the role of relationship quality, identification, and service attributes. Internet Research. 2017 Apr 3; 27(2): 428-448.

39. Chetioui Y, Benlafqih H, Lebdaoui H. How fashion influencers contribute to consumers’ purchase intention. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal. 2020 Aug 20; 24(3): 361-380.

40. Vahdati H, Mousavi Nejad SH. Brand personality toward customer purchase intention: the intermediate role of electronic word-of-mouth and brand equity. Asian Academy of Management Journal. 2016 Jul 1; 21(2): 1–26.

41. Jung J, Kim SJ, Kim KH. Sustainable marketing activities of traditional fashion market and brand loyalty. Journal of Business Research. 2020 Nov 1; 120: 294-301.

42. Du K. The impact of multi-channel and multi-product strategies on firms’ risk-return performance. Decision Support Systems. 2018 May 1; 109: 27-38.

43. Chae H, Ko E, Han J. How do customers’ SNS participation activities impact on customer equity drivers and customer loyalty? Focus on the SNS services of a global SPA brand. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science. 2015 Apr 3; 25(2): 122-141.

44. Su L, Swanson SR. Perceived corporate social responsibility’s impact on the well-being and supportive green behaviors of hotel employees: The mediating role of the employee-corporate relationship. Tourism management. 2019 Jun 1; 72: 437-450.

45. Yang X. Determinants of consumers’ continuance intention to use social recommender systems: A self-regulation perspective. Technology in Society. 2021 Feb 1; 64: 101464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101464

46. Salem MB, Stolfo SJ. Detecting Masqueraders: A Comparison of One-Class Bag-of-Words User Behavior Modeling Techniques. Journal of Wireless Mobile Networks, Ubiquitous Computing and Dependable Applications 2010 Jun; 1(1): 3-13.

FINANCING

No financing for the article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest in the work.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Beeraka Chalapathi; G. Rajini.

Research: Beeraka Chalapathi; G. Rajini.

Writing - original draft: Beeraka Chalapathi; G. Rajini.

Writing - revision and editing: Beeraka Chalapathi; G. Rajini.